ISSN : 2574-2825

Journal of Nursing and Health Studies

Knowledge of Childhood Malaria Prevention and Outcome of Untreated Childhood Malaria Among Mothers/Caregivers of Under-Five Children in Ibadan, Nigeria

Margaret O. Akinwaare1*, Anthonia P. Ekpe, Mary O. Abiona

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

*Corresponding author : Margaret O. Akinwaare, Department of Nursing, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria; Tel: +2348034242253 , Email: margaretakinwaare@gmail.com

Received date: October 29, 2020 ; Accepted date: August 13, 2021; Published date: August 24, 2021

Citation: (2021) Margaret O. Akinwaare Knowledge Of Childhood Malaria Prevention And Outcome Of Untreated Childhood Malaria Among Mothers/Caregivers Of Under-Five Children In Ibadan, Nigeria . J Nurs Health Stud. Vol 5 No.1.

Abstract

Objective

Nigeria is a malaria-endemic area and malaria is the principal cause of childhood mortality as it kills one child every 2 minutes. Adequate knowledge of malaria transmission, symptoms, preventive measures, treatment and consequences of untreated malaria by mothers or caregivers is essential in combating the disease. Therefore, the study investigated Nigerian mothers’/caregivers’ knowledge of malaria prevention and outcome of untreated malaria among under-5 children.

Methods

Descriptive cross-sectional design was adopted, simple random sampling technique was utilized to select one hundred and thirty-two (132) caregivers/mothers from mothers attending Infant welfare clinic in University College Hospital, Ibadan. Self-administered structured questionnaire was used for data collection which was coded and analysed using SPSS -21.

Result

The study reveals that 57(43.2%) of the respondents have good knowledge of malaria prevention, 90(68.2%) take good malaria preventives measures and 68(51.5%) have good knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria. The findings reveal that mothers/caregivers age, marital status, monthly income, parity and educational status are not significantly (p=0.93; p=0.556; p=0.121; 0.712 and p=0.129) associated with knowledge of childhood malaria prevention. Also, mothers/caregivers age, gender, relationship, marital status, monthly income and parity are not significantly (p=0.09; p=0.276; p=0.470; p=0663; p=0.886 and p=0.200) associated with knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria while their educational status is significantly (p=0.012) associated. Also, knowledge of childhood malaria prevention was significantly (p < 0.001) associated with knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

Conclusion

Quite a number of mothers/caregivers of under-five children have poor knowledge of malaria preventives measures which translates into poor practice of preventive measures. Thus, knowledge of preventive measures is associated with knowledge of outcome of untreated childhood malaria.

Keywords: Knowledge, Malaria, Prevention, Under-five children, Child mortality

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a mosquito borne disease in humans and animals (Ukaegbu et al., 2014). It is caused by parasitic protozoans of the genus Plasmodium with species falciparum and vivax and the mosquitoes which act as vector for this disease are female Anopheles funestus, Anopheles mou-cheti, Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles arabiensis (World Health Organisation (WHO) 2015). The disease is also known as aque, intermittent fever, marsh fever, and the fever (Beale & Block 2011; Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) 2010). Also, Malaria is a life-threatening vector-borne disease which is caused by transmission of malaria parasite through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. High-risk populations of malaria infections are pregnant women, under-five children, forest workers and other immune-compromised people. Among them, children under-five have more chance to get infection, illness, and death due to severe malaria in high transmission areas of malaria (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2017a).

Moreover, it is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions because rainfall, warm temperatures, and stagnant waters provide habitats suitable for mosquito to breed. Five species of plasmodium can infect and be transmitted by humans, however, majority of deaths from malaria are caused by plasmodium falciparum while plasmodium vivax, plasmodium ovale, and plasmodium malarie causes a generally milder form of malaria that is rarely fatal. The zoonotic species, plasmodium knowlesi is prevalent in Southeast Asia; it causes malaria in macaques, but can also cause severe infections in humans.

In Africa, it is estimated that malaria kills one child every 2 minutes (WHO Global Malaria Programme, 2015). According to the estimates from the World Health Organisation (WHO), there were 214 million new cases of malaria worldwide in 2015 with an estimated 438 000 malaria deaths (WHO Global Malaria Programme, 2015). Most of these cases (88%) and deaths (90%) were recorded in the African region (WHO Global Malaria Programme, 2015). Nigeria and Republic of Congo are two major African Countries contributing to the high malaria burden, as 36% of the malaria cases worldwide occurred in these two countries (World Malaria Report, 2016). According to WHO, nearly half of the world populations are living in malaria at risk areas and latest estimated 216 million cases occurred globally in 2016 (WHO, 2017c). In South East Asia, 1.35billion people are living in malaria-endemic areas, and there were 1.3 million reported malaria cases and 14.6 billion estimated malaria cases by WHO in 2016 (WHO, 2017c).

Moreover, there were 445,000 malaria deaths globally, and 91% and 6% of global malaria deaths were attributed by Africa and south East Asia (reported 557 malaria death, estimated 26600 malaria deaths by WHO in 2016) respectively according to WHO 2017 report (WHO, 2017c). In addition, estimated 303,000 malaria deaths had occurred among children under-five years which were accounted for 70% of the global total malaria deaths in 2015 (WHO, 2016) and every 2 children per 1000 live births die because of malaria globally according to WHO and Maternal and Child Epidemiology Estimation Group (MCEE)’s estimated 2015 data (MCEE, 2015).

However, this large burden has led to the development and setting of several strategies and targets aimed at malaria control, and where possible its elimination. The Global Strategy for Malaria, 2016 to 2030 targets a 90% reduction in the incidence and mortality rates of malaria, as well as an elimination of malaria in 35 of its endemic countries by 2030. One of the Standard Developmental Goals (SDG’s) target indicators is to end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other neglected tropical diseases by 2030 (World Malaria Report, 2016). Efforts and progress in implementation of control programs has yielded significant results. Between 2000 and 2015, the incidence of malaria has declined globally by about 37%, likewise death from malaria declined globally by 60%. Progress has been witnessed towards global elimination as increasing number of countries have moved towards malaria elimination (WHO & United Nations Children Education Funds. (UNICEF), 2013; WHO, 2014).

Furthermore, the classic symptom of malaria is paroxysm—a cyclical occurrence of sudden coldness followed by shivering and then fever and sweating, occurring every two days (tertian fever) in P. vivax and P. ovale infections, and every three days (quartan fever) for P. malariae. P. falciparum infection can cause recurrent fever every 36–48 hours, or a less pronounced and almost continuous fever. Severe malaria is usually caused by P. falciparum (often referred to as falciparum malaria). Symptoms of falciparum malaria arise 9–30 days after infection (Bartoloni and Zammarchi, 2012). The disease leads to numerous complications in children such as anaemia, pulmonary oedema, renal failure, hepatic dysfunction and coma (Onyesom and Onyemakonor, 2011).

In Nigeria, the burden of malaria is well documented and has been shown to be a big contributor to the economic burden of disease in communities where it is endemic and is responsible for annual economic loss to the tune of 132 billion Naira (Babalola, Olarewaju, Omeonu, Adefelu & Okeowo, 2013). It is estimated that out of 300,000 deaths occurring each year, 60% of outpatient visits and 30% hospitalizations are all caused by malaria (Uzochukwu, Ezeoke, Emma-Ukaegbu, Onwujekwe, & Sibeudu, 2013). Malaria has been the main cause of deaths in Nigeria especially in children (National Population Commission, National Malaria Control Programme, ICF International, 2012). No doubt Nigeria is a malaria-endemic area and malaria is the principal cause of childhood mortality.

However, Nigeria is currently a malaria endemic country with its entire population (186 million) at risk of contracting malaria (World Malaria Report, 2015), and a whopping 76% of this population at high risk. In 2015, Nigeria contributed about 29% of the malaria cases and 26% of the malaria deaths worldwide (World Malaria Report, 2016). These large figures imply that Nigeria’s success in tackling malaria control will play a large part in the actualization of the global goals.

Poverty has been associated with malaria. This could pose a barrier in the control of malaria as 80 million Nigerians are currently living in poverty (WHO Fact sheet on World Malaria report 2012). Despite reported decline in infection and mortality (Murray, Rosenfeld, Lim, Andrews, Foreman, et al., (2012), malaria remains the fourth leading cause of under-five mortality in the sub-region (WHO, 2015). Children are particularly susceptible to the disease due to their poorly developed immune system. It is against this background that this study assessed childhood malaria prevention and outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW

Nigeria and Malaria Burden

Nigeria contributes the majority of the Africa malaria burden as its the most populous country in Africa, and being a tropical country Nigeria has some favorable climatic characteristics which positively influences the breeding and survival of the female anopheline mosquitoes.. Most (97%) of the malaria in Nigeria are mainly due to Plasmodium falciparum, with Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae affecting only a few persons.. Malaria remains a major public health problem in Nigeria as it accounts for more cases and deaths than in any other country in the world. There are an estimated 100 million malaria cases with over 300,000 deaths per year in Nigeria. Malaria accounts for 60% of outpatient visits and 30% of hospitalizations among children under 5 years of age in Nigeria (Nigeria Malaria Fact Sheet, 2011). This implies a huge loss in terms of financial resources and man hours and in the case of the school age child, loss of school hours (Uguru, et al., 2009; Salihu, 2013; Onwujekwe, 2010). In line with the World Health Organization recommendation, the country has adopted the Test, Treat, and Track (3T) strategy with all suspected cases of malaria properly diagnosed using Rapid Diagnostic Tests or microscopy, treated promptly with recommended artemisinin based combination therapy (ACT) if the result is positive and documented (FMoH, 2015).

Prevention of Malaria

The two components of malaria prevention are reducing exposure to infected mosquitoes and chemoprophylaxis.

Chemoprophylaxis

All children (including immigrants and those traveling to a malaria-endemic region to visit friends and relatives) are expected to take an appropriate antimalarial drug. The choice of this chemoprophylactic agent should be based on the presence of chloroquine-resistant or mefloquine-resistant strains in the specific area. Intermittent administration of a full therapeutic dose of an antimalarial drug (or a combination of drugs) at specified timepoints, known as Intermittent Preventive Treatment (IPT)had shown great benefit in areas of high transmission and for specific risk groups (infants, high risk children and/or pregnant women). Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine is particularly suited for this approach as it has a long half-life.

A further development of IPT is Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) which is now being recommended by WHO for the prevention of falciparum malaria among children less than 5 years of age in areas with highly seasonal malaria transmission as the Sahel sub-region. A complete 3-day treatment course of amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (AQ+SP) should be given to children aged between 3 and 59 months at monthly intervals, to a maximum of four doses during the malaria transmission season. SMC should not be given to children with severe acute illness or unable to take oral medication, to HIV positive patients on co-trimoxazole, to a child who has received a dose of either AQ or SP drug during the past month or who is allergic to either drug. The recommendation is based on results from 7 studies on SMC (IPTc) showing a reduction of 75% in malaria episodes in children less than 5 years of age without significant side effects.(WHO, 2012; WHO, 2017c).

Vector Control

Key interventions currently recommended by WHO for the control of malaria in endemic areas are the use of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) and/or indoor residual spraying (IRS) for vector control, and prompt access to diagnostic testing of suspected malaria and treatment of confirmed cases. Community randomized trials in Africa have shown that full coverage with insecticide-treated nets can halve the number of episodes of clinical malaria and reduce all-cause mortality in children younger than 5 years of age. When used by pregnant women, insecticide-treated nets can lead to substantial reductions in low birth weight, placental parasitaemia, stillbirths, and miscarriages.

Repellents

Use of topical insect repellent is an important component of the prophylaxis against arthropod bite vector borne diseases too. Rational repellent prescription for a child must take into account age, active substance concentration, topical substance tolerance, nature and surface of the skin to protect, number of daily applications, and the length of use in a benefit-risk ratio assessment perspective. The repellents currently recommended in the 2012 edition of the Yellow Book comprise: DEET, Picaridin KBR 3023 or Icaridin , Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or PMD ( or IR3535 Efficacy and duration of protection for all these products are markedly affected by ambient temperature, amount of perspiration, exposure to water, abrasive removal, etc.

Furthermore the following age restriction for DEET containing products is mentioned: should not be used on children less than two years old, and use should be restricted for children between two and twelve years old, except where motivated by the risk for human health through e.g. outbreaks of insect-borne diseases. However, DEET is not recommended for children with a history of seizures and for pregnant and lactating women, because of its potential neurotoxicity on the fetus and newborn.

Other methods for malaria prevention include community participation and health education strategies which goes a long way in promoting awareness of malaria and the importance of control measures, these have been successfully used to reduce the incidence of malaria in some areas of the developing world. Recognizing the disease in the early stages can prevent the disease from becoming fatal and education can also inform people on preventive measures to put in place to lower transmission. .

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study Design

A Descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in the form of a survey among mothers of under-fives attending Infant Welfare Clinic, University College Hospital, Ibadan to assess their knowledge on prevention and outcomes of untreated malaria.

Study Setting

This study was carried out in infant welfare clinic now known as centralize immunization clinic Centre in University College Hospital (UCH) Ibadan, Ibadan north local government area, Oyo state which is located in the south west geopolitical zone of Nigeria. The clinic carried out their activities from Monday to Friday.

Study Population and Sampling Technique

The study population were mothers/caregivers of under-five children attending infant welfare clinic in UCH, Ibadan, who were available at the time of administration of the questionnaires in the clinic.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size for this study was determined using (Araoye, 2004) sample size formula stated as n = _____N______

[1 + N (e)2]

with the following assumption: Population of study participants: 171, Degree of error of tolerance: 5%., Attrition rate: 10%, 132 respondents were therefore recruited for the research.

Simple random sampling was then used to select the mothers of under-five children attending infant welfare clinic of University College Hospital, Ibadan. These mothers were randomly selected from the updated record of mothers of under-five children who attend the clinic in University College Hospital.

Instrument for Data Collection

The data were collected using structured self-administered questionnaire. This was designed to assess the knowledge of malaria prevention and outcome of untreated malaria among mothers of under-five children attending infant welfare clinic in UCH, Ibadan.

Validity and Reliability of Instrument

Face and content validity of the instrument were ensured by the use of relevant literatures in evaluating the study instrument for clarity and ambiguity. The content of the questionnaire was also matched with the study objectives and research questions.

To ensure the reliability and consistency of the instrument, a pre-test was carried out using 10 mothers of under-five children from a Primary Health Centre in Ibadan. A reliability coefficient of 0.76 was gotten which showed that the instrument was reliable for the study.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of University of Ibadan/University College, thereafter a formal permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Chairman Medical Advisory Committee, UCH, Ibadan. A written informed consent which was translated to Yoruba Language for the mothers who cannot read and understand English was obtained from all participants and they were assured of confidentiality of every information given. The mothers were also informed of freedom to withdraw from the study without any harm. The This study will benefit the respondent because the study does not only asses the knowledge of caregivers/mothers about malaria prevention and outcome of untreated malaria but the result of the finding will revealed the knowledge of caregivers’ about malaria prevention and outcome of untreated malaria and barriers to malaria prevention which will help the health care system in Nigeria to create awareness as a way of educating the caregivers/mothers on their under-five children protection and health. The Participants were not exposed to harm or injury during the conduct of the study as only their time was required.

Method of Data Analysis

Data obtain were screened for errors and completeness. Analysis was done using IBM-SPSS version 22.0software. Descriptive statistics of frequency counts, simple percentage, mean + SD was obtained to summarize and present the results. Chi-square test was carried out to test the association between knowledge of malaria prevention and outcome of untreated malaria is not statistically significance at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic Characteristics of the respondents

The table 1 below reveals that 37.9% of the respondents were age between 21 and 30 years with the mean ± SD age of 36.9 ± 11.4; 83.3% are female; 69.7% had mother relationship with under-five child; 34.8% of the respondents are civil servant; 72.0% had tertiary institution certificate; 38.6% of the respondent earn below 21 thousand naira monthly with mean monthly income of 41.3± 3.8; 57.6% had 2-4 children with mean number of children delivered by the participants 3.0 ± 1.6; while 46.2% of the respondents had two children that are under-five years of age.

Table 1:Demographic Characteristics of the respondents (N = 132).

| Variable | Frequency(N) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groupBelow 2121 – 3031 – 4041 – 50Above 50Mean ± SD = 36.9 ± 11.4 | 250343016 | 1.537.925.822.712.1 | ||

| GenderMaleFemale | 22110 | 16.783.3 | ||

| Relationship with under five childMotherFatherGrandparentOthers | 92171112 | 69.712.98.39.1 | ||

| Marital StatusSingleMarriedSeparate/Divorced | 151143 | 11.486.42.3 | ||

| OccupationTradingFarmingHousewifeCivil servantSelf employedArtisanStudentOthers | 224946361122 | 16.73.06.834.827.30.89.11.5 | ||

| ReligionChristianityIslamTraditional | 90402 | 68.230.31.5 | ||

| Level of educationNo formal educationPrimarySecondaryTertiary | 272895 | 1.55.321.272.0 | ||

| TribeYorubaIgboHausaOthers | 1061565 | 80.311.44.53.8 | ||

| Monthly Income (#’000)Below 2121 – 4041 – 6061 – 80Above 80Mean ± SD = 41.3 ± 3.8 | 513618819 | 38.627.313.66.114.4 | ||

| Parity (Number of Children)12 – 4Above 4Mean ± SD = 3.0 ± 1.6 | 287628 | 21.257.621.2 | ||

| Child’s Age (years)OneTwoThreeFour and aboveMean ± SD = 3.0 ± 1.5 | 33261954 | 25.019.714.440.9 | ||

| Number of under five childrenOneTwoThreeFourMean ± SD = 1.8 ± 0.8 | 4861194 | 36.446.214.43.0 | ||

Knowledge about Malaria Prevention

Table 2 below shows that 93.9% of the respondent are aware of malaria, 82.6% are also aware of malaria preventive measures, while 80.3% got their information about malaria from health centres/clinics. 86.4% of the respondent agreed that the use of ITNs is an appropriate preventive measure against malaria while 91.7% are aware that malaria can be treated by taking of antimalarial drug from health facility.

Table 2: Respondent’s knowledge about Malaria Prevention (N = 132).

| Statement | Response | Frequency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of malaria | YesNo | 124(93.9)8(6.1) | |||

| Awareness of malaria prevention education measures | YesNoDon’t know | 109(82.6)21(15.9)2(1.5) | |||

| Source(s) of information about malaria | Family/FriendsChurch/SchoolHealth centres/ClinicsHealth workersPosters/leafletsMedia (TV, Radio, Newspaper) | 72(54.5)62(47.0)106(80.3)86(65.2)69(52.3)71(53.8) | |||

| Mosquito bite can cause of malaria | CorrectIncorrect | 120(90.9)12(9.1) | |||

| Malaria can be transmitted in following ways | Mosquito biteDirty environment/unhygienic practicesBlood transfusion /placenta (mother to child)Stagnant water | 121(91.7)89(67.4)66(50.0)85(64.4) | |||

| People who are at risk of malaria | Farmers/Forest workersPeople living with HIV/AIDSUnder-five childrenPregnant women | 84(63.6)62(47.0)85(64.4)92(69.7) | |||

| Biting time of malaria is at night | CorrectIncorrect | 86(65.2)46(34.8) | |||

| Symptoms of malaria: | Cold/chill and rigor/shiveringNausea and vomitingBody pain/Abdominal painInability to eat/loss of energyHeadacheYellow eyes and urineFever/high temperature | 104(78.8)92(69.7)82(62.1)92(69.7)98(74.2)68(51.5)109(82.6) | |||

| Malaria appropriate preventive measures are: | Use of ITNsUse of repellantTaking anti-malaria medicationKeeping the house and surrounding clean | 114(86.4)87(65.9)94(71.2)106(80.3) | |||

| Malaria can be treated by taking of antimalarial drug from health facility | CorrectIncorrect | 121(91.7)11(8.3) | |||

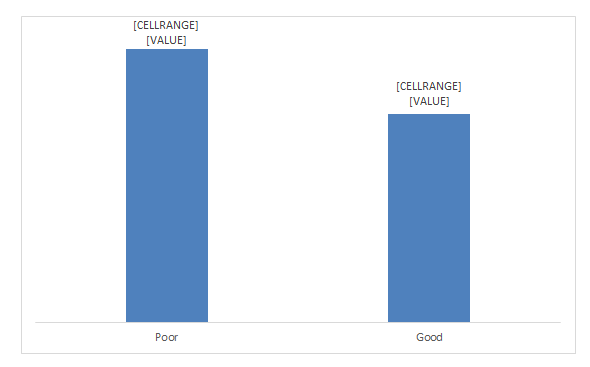

Figure 2: Shows that 56.8% of the respondents have poor knowledge of malaria prevention and 43.2% have good knowledge of malaria prevention among under-five children.

Practice of malaria preventive measures

Table 3 below shows that 53.0% of the respondents wear long sleeves clothes to prevent mosquito bites, , 51.5% eat healthy diet/ avoid fruits, 84.8% uses bed nets/ITNs, 75.8% uses mosquito repellant cream, 77.3% drain stagnant water and cut bushes around the house, 78.0% spray insecticide, 83.3% avoid mosquito bites, 62.9% take preventive medication, 30.3 stay out of sun/ cold weather, 48.5%keep doors and windows closed, 59/1% uses mosquito coil, 63.3% cover their water container, 66.7% clean dark corners in the house and 73.5% maintain good personal and environmental hygiene as malaria preventive measures.

Table 3: Respondent’s practice of malaria preventive measures among under-five children (N = 132).

| Statement | Response | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

Malaria preventive measures |

Wearing long sleeves clothing Eating healthy diet/avoid fruits Using bed nets/ITNs Use of mosquito repellant cream Draining stagnant water Cutting of bushes around the house Spraying of insecticide Avoiding mosquito bites Taking preventive medication Staying out of sun/cold weather Keeping doors and windows closed Using of mosquito coil Good personal hygiene/environmental hygiene Covering water container Cleaning dark corners in the house |

70(53.0) 68(51.5) 112(84.8) 100(75.8) 102(77.3) 102(77.3) 103(78.0) 110(83.3) 83(62.9) 40(30.3) 64(48.5) 78(59.1) 97(73.5) 84(63.6) 88(66.7) |

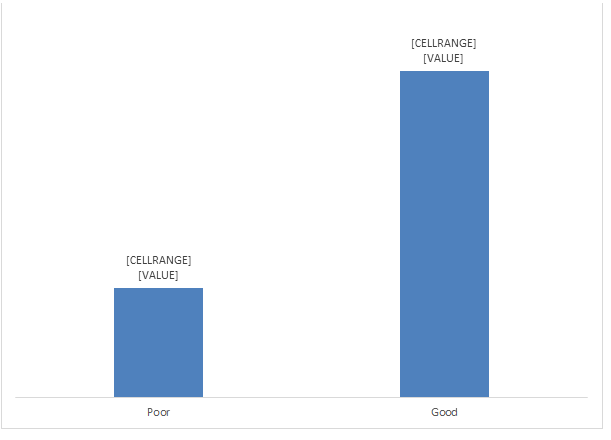

Figure 3: Shows that 31.8% of the respondents have poor practice of malaria preventive measures and 68.2% have good practice of malaria preventives measures among under-five children.

Knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria

Table 4 below revealed the response of the participants on outcome of untreated malaria, this ranges from unconsciousness (54.5%) , Prostration (27%), death (73.5%)

Table 4.Respondent’s knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

| Statement | Response | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The outcome of untreated malaria among under-five includes: | UnconsciousnessMultiple convulsionsDeathHigh/more cost of treatmentAnaemia/JaundiceBig spleen diseaseCognitive and behavioural impairmentProstrationHyperpyrexia (very high fever)Hypoglyceamia (low glucose)Hypoglobinuria (low red blood cell) | 72(54.5)73(55.3)97(73.5)91(68.9)57(43.2)49(37.1)55(41.7)30(22.7)85(64.4)66(50.0) |

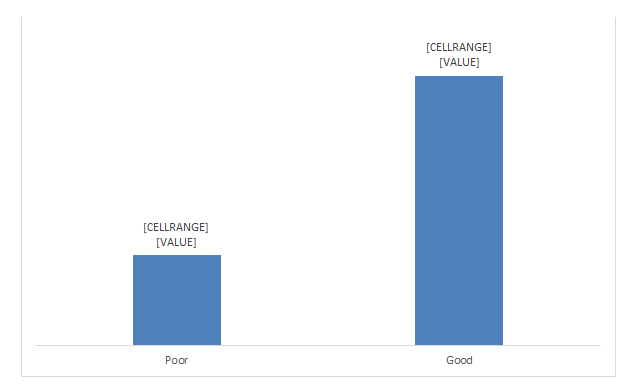

Figure 4: shows that 48.5% of the respondents have poor knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria and 51.5% have good knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

Barriers to prevention of malaria

Table 5 shows that 65.9% believed that the insecticide on the long lasting ITNs can be dangerous to children who sleep under them while 72.7% are of the opinion that mosquito coils cause bad smell and harmful to health of children, 62.9% reported that children cannot sleep well under LLITNs when the weather is warm, 34.8% also opined that mosquito repellant are difficult to buy, and 55.3% of the respondents attest that health center is not too far to seek treatment in case of fever.

Table 5: Respondent’s barriers to prevention of malaria among under-five children.

| Frequency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

| The insecticide on the long lasting ITNs can be dangerous to children who sleep under them | 87(65.9) | 31(23.5) | 14(10.6) |

| Children cannot sleep well under LLITNs when the weather is warm | 83(62.9) | 24(18.2) | 25(18.9) |

| It is very hot when children wear long clothes at night time during hot season | 101(76.5) | 20(15.2) | 11(8.3) |

| Mosquito repellants are difficult to buy | 46(34.8) | 73(55.3) | 13(9.8) |

| Mosquito coils causes bad smell and harmful to health of children | 96(72.7) | 26(19.7) | 10(7.6) |

| Multiple breeding sites around the house make it difficult to clean all the breeding sites | 77(58.3) | 44(33.3) | 11(8.3) |

| It is too far going to health facility centre to seek treatment if children get fever | 52(39.4) | 73(55.3) | 7(5.3) |

Testing of Hypotheses

Hypothesis One (H01): There is no significant association between mothers/caregivers’ Socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge of malaria preventive measures among under-five children attending infant welfare clinic in UCH, Ibadan.

The below table 6 shows that mothers/caregivers gender and relationship were significantly (p=0.045; p=0.028) associated with level of knowledge of malaria preventive measures among under-five children while their age, marital status, monthly income, parity and educational status were not significantly (p=0.93; p=0.556; p=0.121; 0.712 and p=0.129) associated with level of knowledge of malaria preventive measures among under-five children.

Table 6: Cross – tabulation of mothers/caregivers’ Socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge of malaria preventive measures among under-five children.

| Knowledge of malaria preventive measures | Remark | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Good | d.f | X2-value | p-value | |||

| Age group (yrs) | Below 2121 – 3031 – 4041 – 50Above 50 | 0 (0.0%)10 (23.8%)12 (28.6%)13 (31.0%)7 (16.7%) | 2 (2.2%)40 (44.4%)22 (24.4%)17 (18.9)9 (10.0) | 4 | 7.03 | 0.93 | insignificant |

| Gender | MaleFemale | 11 (26.2%)31 (73.8%) | 11 (12.2%)79(87.8%) | 1 | 4.02 | 0.045 | Significant |

| Relationship with the child | MotherFatherGrandparentOther | 27 (64.3%)10 (23.8%)4 (9.5%)1 (2.4%) | 65 (72.2%)7 (7.8%)7 (7.8%)11 (12.2%) | 3 | 8.76 | 0.028 | Significant |

| Marital status | SingleMarriedSeparate/Divorce | 3 (7.1%)38 (90.5%)1 (2.4%) | 12 (13.3%)76 (84.4%)2 (2.2%) | 2 | 1.17 | 0.556 | Insignificant |

| Monthly Income (#’000) | Below 2121 – 4041 – 6061 – 80Above 80 | 16 (38.1%)14 (33.3%)5 (11.9%)0 (0.0%)7 (16.7) | 35 (38.9%)22 (24.4%)13 (14.4%)8 (8.9%)11 (16.2%) | 4 | 5.06 | 0.121 | Insignificant |

| Parity | 12 – 4Above 4 | 10 (23.8%)22 (52.4%)10 (23.8%) | 18 (20.0%)54 (60.0%)18 (20.0%) | 2 | 0.68 | 0.712 | Insignificant |

| Educational status | PrimarySecondaryTertiaryNon formal | 3 (7.1%)10 (23.8%)27 (64.3%)2 (4.8%) | 4 (4.4%)18 (20.0%)68 (75.6%)0 (0.0%) | 3 | 4.87 | 0.129 | Insignificant |

Note: Fisher’s exact result was recorded for small cell.

Hypothesis Two (H02): There is no significant association between mothers/caregivers’ Socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children attending infant welfare clinic in UCH, Ibadan.

The below table 4.7 shows that mothers/caregivers age, gender, relationship, marital status, monthly income and parity were not significantly (p=0.09; p=0.276; p=0.470; p=0663; p=0.886 and p=0.200) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children while their educational status was significantly (p=0.012) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

Table 7: Cross – tabulation of mothers/caregivers’ Socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

| knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria | Remark | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Good | d.f | X2-value | p-value | |||

| Age group (yrs) | Below 2121 – 3031 – 4041 – 50Above 50 | 2 (3.1%)25 (39.1%)11 (17.2%)16 (25.0%)10 (15.6%) | 0 (2.2%)25 (36.8%)23 (33.8%)14 (20.6)6 (8.8) | 4 | 6.86 | 0.09 | insignificant |

| Gender | MaleFemale | 13 (20.3%)51 (79.7%) | 9 (12.2%)59(86.8%) | 1 | 1.19 | 0.276 | insignificant |

| Relationship with the child | MotherFatherGrandparentOther | 41 (64.1%)11 (17.2%)6 (9.4%)6 (9.4%) | 51 (75.0%)6 (8.8%)5 (7.4%)6 (8.8%) | 3 | 2.53 | 0.470 | insignificant |

| Marital status | SingleMarriedSeparate/Divorce | 6 (9.4%)57 (89.1%)1 (1.6%) | 12 (13.3%)57 (83.8%)2 (2.9%) | 2 | 0.89 | 0.663 | Insignificant |

| Monthly Income (#’000) | Below 2121 – 4041 – 6061 – 80Above 80 | 23 (35.9%)18 (28.1%)10 (15.6%)3 (4.7%)10 (15.6%) | 28 (41.2%)18 (26.5%)8 (11.8%)5 (7.4%)9 (13.2%) | 4 | 1.21 | 0.886 | Insignificant |

| Parity | 12 – 4Above 4 | 17 (26.6%)32 (50.0%)15 (23.4%) | 11 (16.2%)44 (64.7%)13 (19.1%) | 2 | 3.19 | 0.200 | Insignificant |

| Educational status | PrimarySecondaryTertiaryNon formal | 2 (3.1%)21 (32.8%)40 (62.5%)1 (1.6%) | 5 (7.4%)7 (10.3%)55 (80.9%)1 (1.5%) | 3 | 10.76 | 0.012 | significant |

Note: Fisher’s exact result was recorded for small cell.

Hypothesis Four (H03): There is no significant association between mothers/caregivers knowledge of malaria preventive measures and knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children attending infant welfare clinic in UCH, Ibadan.

The below table 8 shows that mothers/caregivers knowledge of malaria preventive measures was significantly (p < 0.001) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

Table 8: Cross – tabulation of mothers/caregivers knowledge of malaria preventive measures and knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children.

| Knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Good | d.f | X2-value | p-value | Remark | ||

| Knowledge of malaria preventive measures | PoorGood | 32 (76.2%)32 (35.6%) | 10 (23.8%)58 (64.4%) | 1 | 18.93 | <0.001 | Significant |

DISCUSSION

The Socio-demographic characteristics of the study revealed that about two-fifth of the respondents were age between 21 and 30 years with the mean age being 36.9 ± 11.4,this shows that most of the caregivers’/mothers were between this age range. From the data obtained, more than three-quarter of the respondents that attend infant welfare clinic are female, about two-third were mother in relationship with under-five child, and the distribution of the respondents according to marital status showed that more than three-quarter were married, and their occupation showed that about one-third were civil servants. According to the respondent’s religion, slightly above two-third practice Christianity, while for their educational level about three-quarter had tertiary institution certificate, this shows they were mostly educated and slightly above one-third of the respondents earn below 21 thousand naira as their monthly income. However, according to the respondent’s parity two-third had 2-4 children, while slightly below half of the respondents had their child’s age to be 4years and above and had maximum of two under five children.

The findings of the study discovered that there was significant relationship between the caregiver’s gender and knowledge of malaria preventive measures (P= 0.045), though age, marital status, monthly income, parity and educational status were not significantly associated. This is contrary to Romay-Barja et al (2016) who revealed that socio-demographic such as age, sex, marital status, occupation, education and economic status statistically influence knowledge of malaria prevention among caregivers of under-five children.

Also, the findings of this study showed that mothers/caregivers age, gender, relationship, marital status, monthly income and parity were not significantly (p=0.09; p=0.276; p=0.470; p=0663; p=0.886 and p=0.200) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children while their educational status was significantly (p=0.012) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children. This is contrary to Romay-Barja et al (2016) who stated that socio-demographic such as age, sex, marital status, occupation, education and economic status statistically influence knowledge of malaria and outcome of untreated malaria among caregivers of under-five children.

Knowledge of malaria prevention: Knowledge of malaria prevention among care givers is significant in the fight against this infection as early treatment of childhood malaria depends upon mothers’ knowledge about malaria and prompt recognition of signs and symptoms of the disease (Oyekale, 2015).

Concerning the knowledge of malaria prevention, the findings revealed that a large proportion (93.9%) of the respondents were aware of malaria and its preventive measures (82.6%), Mainly, slightly below half of the caregivers had good knowledge of malaria preventive measures among under five children . Majority of the respondents (90.9%) know that mosquito bite can transmit malaria and that malaria can be treated by taking of antimalarial drug from health facility (91.7%). A larger proportion of the respondents were knowledgeable about appropriate preventive measures which are use of ITNs (86.4%), use of repellant (65.9%), taking anti-malaria medication (71.2%) and keeping the house and surrounding clean (80.3%)..

The findings of this present study is consistent with other studies where about three-quarter of caregivers had good knowledge of malaria preventive measures (Salawu 2013, Min, 2014, Han 2017). Although, , this study findings is contrary to the report of several studies who reported inadequate knowledge of malaria prevention; according to the finding of a study conducted in Jos, Nigeria only 49% of respondents had adequate knowledge concerning malaria causation, transmission and treatment (Ogbonna, Daboer and Chingle, 2010). In Oluwasogo, (2015), only one-quarter of the under-five caregivers identified ITNs as preventive measure of malaria, Ogonna et al (2010) likewise reported that just one-quarter of the respondents attributed malaria to mosquito bite while in Olorunfemi and Adekoya, (2013), 40% of the respondents did not know the exact cause of malaria butattributed it to sunlight(20%) and mosquito (16%). Also, Zewdie & Birhanu (2017) and Ashikeni, Envuladu, Zoakah, (2013 reported that the overall knowledge of respondents in their study regarding malaria prevention was very low.

Factors such as educational level, marital status, family income, and occupation have been discovered and reported by several studies to be associated with mothers/caregivers knowledge about malaria and its management (Al 2011, Borah & Sarma 2012; Jombo, Araoye & Damen 2011; Sato 2012, Yadav 2010, Adebayo et al 2015, Romay-Barja et al., 2016) though this is in contrast with the findings of this study where age, marital status, monthly income, parity and educational status of the caregivers were not significantly (p=0.93; p=0.556; p=0.121; 0.712 and p=0.129) associated with level of knowledge of malaria preventive measures. However the findings of this present study discovered an association between the gender of caregivers and knowledge of malaria prevention practices which was consistent with the report of Opare (2013).

Malaria preventive measures

Primary health care as stated in the Alma Ata declaration underscores the importance of health education as one of the key methods of preventing and controlling outcome of untreated malaria and the prevailing health problems. Malaria accounts for more than 70% of hospital attendance and the commonest cause of death among the Under-fives (WHO, 2015)

As regards the caregivers malaria preventive measures among under-five children, the study findings revealed that slightly above two-third (68.2%) of the caregivers had good practice of malaria preventives measures among under-five children as approximately half wore long sleeves clothes to prevent malaria and keep doors and windows closed, majority uses bed nets/ITNs to avoid mosquito bites, three-quarter uses mosquito repellant cream, draining of stagnant water and cut bushes around the house, spraying of insecticide and maintaining of good personal and environmental hygiene as malaria preventive measures. This is consistent with preventive measures highlighted by several studies which include using insecticide-treated nets, environmental sanitation and indoor insecticide spraying (Mutero et al 2012, Orimadegun & Ilesanmi 2015, Ameyaw et al., 2015 and Han (2017) reported that some caregivers use mosquito coil to prevent malaria.

However prompt and effective treatment of malaria with an effective anti-malarial drug within 24 hours of fever onset was one of the strategies used to control malaria in Malawi (Wilson, et al., 2012). On the contrary, some caregivers have misconceptions about malaria prevention measures which include using herbal medicine and use of antibiotics (Adebayo et al., 2015). Several studies carried out in Nigeria and other countries (Mazigo 2010, Tobin-West, 2016. Al., 2011, Okafor & Odeyemi, 2012, Adams 2015, Bisi-Onyemaechi, 2017, ), revealed that socio-demographic such as sex, marital status, educational status, number of under-five children, age of under-five children and economic status have influence caregivers preventive measures against malaria by the use of insecticide-treated net among caregivers of under-five children.

Knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria

The study findings revealed that approximately half of the caregivers had good knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children as majority reported death, high/more cost of treatment and very high fever, unconsciousness, multiple convulsion, anaemia/jaundice, cognitive and behavioural impairment and low red blood cell while one third reported big spleen and prostration as outcomes of untreated malaria among under-five children. This study finding is in line with WHO statement on outcome of untreated malaria or severe (SM) which is observed in the presence of impaired consciousness, acidosis, hypoglycemia, anemia, acute kidney injury, jaundice, pulmonary edema, significant bleeding, shock, and hyper-parasitaemia (WHO, 2014). Young et al (2012) also reported increased risk of disease severity and death, especially in young children as outcome of untreated malaria. Halliday et al (2012) on the other hand highlighted the following conditions as outcomes of untreated malaria which include decorticate or decelerate posturing, nystagmus, dysconjugate gaze, papilledema, retinal hemorrhages, and altered respiration. Beer et al (2012) reported a child’s life can be threatened with this disease as malaria affects the caregivers’ social life, economic condition because they cannot work if their children are sick as they have to pay in order to get diagnosis and treatment to cure that disease. Bangirana, et al (2011) additionally reported that children with untreated malaria or severe malaria were found to be left with lifelong effects, particularly in the area of neuropsychological functioning, including cognitive and behavioral domains.

The finding of this present study showed that mothers/caregivers age, gender, relationship, marital status, monthly income and parity were not significantly (p=0.09; p=0.276; p=0.470; p=0663; p=0.886 and p=0.200) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children though their educational status was significantly (p=0.012) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children. This is contrary to Romay-Barja et al (2016) who stated that socio-demographic such as age, sex, marital status, occupation, education and economic status statistically influence knowledge of malaria and outcome of untreated malaria among caregivers of under-five children.

Interestingly, mothers/caregivers knowledge of malaria preventive measures was significantly (p < 0.001) associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children, however this inconsistent with the findings of Hans (2017) who reported that there was no association between outcome of untreated malaria and preventive practices.

Barriers to prevention of malaria

Several barriers were identified from this study to hinder prevention of malaria. Majority of the caregivers reported that insecticide on the long lasting ITNs can be dangerous to children who sleep under especially during warm weather, these nets become very hot when children wear long clothes at night during hot season Also, bad odours of mosquito coils which was believed to be harmful to health of children were identified as one of the barriers. , it is. About half of the caregivers however reported hindrance to malaria prevention from multiple breeding mosquito sites around the house which is difficult to clean/eradicate completely, coupled with the fact that Primary health care center is far to seek treatment if children have fever. Some of the respondents reported mosquito repellants being difficult to buy as the barriers to prevention of malaria among under-five children.

These identified barriers from the study were in line with Beer (2012) who reported that during the hot season, children cannot sleep under bed net as it is so hot and caregivers assume that malaria transmission is reduced during dry seasons likewise, Ouathara, et al (2011) reported that people did not like mosquito bed nets because they were associated with heat, suffocation and bad smell. Other reasons identified as barriers by caregivers is the fact that when LLIN need to replace, they have to buy a new one and because it cost high, they cannot afford to buy new ones after the effect of LLIN had been reduced.

Conclusion

It has been established that children bear the heaviest burden of malaria attack which is either treated at home or in the hospital. Early recognition and appropriate treatment can go a long way in minimizing the outcome of the disease. The study findings revealed that slightly above two-third of the caregivers had good practice of malaria preventives measures among under-five children and approximately half of the caregivers had good knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children. Mothers/caregivers knowledge of malaria preventive measures was discovered to be significantly associated with level of knowledge of outcome of untreated malaria among under-five children. Preventive measures practices utilized by the respondents against malaria include sleeping under ITNs, use of repellants, draining of stagnant water to mention a few. However, several barriers were identified as hindrance to prevention of malaria which affected the respondents’ preventive measures, some of which are belief that the ITNs is dangerous for children, mosquito coils seen as harmful to the children, inability to completely eradicate mosquito breeding sites and delay in accessing health care centers due to distance. There is need to increase public awareness of malaria and its preventive measures, the researchers therefore recommend that health education program be implemented among caregivers of under-5 children and awareness campaign be made on media or health talks given to caregivers, drugs sellers, schools, church and community.

REFERENCES

- Adams, M. D (2015) Predictors of malaria prevention and case Management among children under-five in three African countries analysis of

- demographic health surveys (dhs) malaria indicator surveys (Doctor Of Philosophy) The University Of Utah.

- Adaobi I Bisi-Onyemaechi CNO, Ugo N Chikani, Ikechukwu F, Ogbonna, Adaeze C, Ayuk, (2017)Determinants of use of insecticide-treated nets among caregivers of under-five children in Enugu, South East Nigeria.

- Adebayo, A M Akinyemi, O O, & Cadmus E O (2015) Knowledge of malaria prevention among pregnant women and female caregivers of under-five children in rural southwest Nigeria PeerJ 3 e792.

- Adedotun A A, Salawu O T, Morenikeji, O A and Odaibo A B (2013) Plasmodial infection and haematological parameters in febrile patients in a hospital in Oyo town South-western Nigeria Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology Vol. 5(3), pp. 144-148.

- Akogun, O B & John K K (2012) Illness-related practices for the management of childhood malaria among the Bwatiye people of north-eastern Nigeria Malar J 4: 13.

- Ameyaw E, Dogbe J, Owusu M (2015) Knowledge and practice of malaria prevention among caregivers of children with malaria admitted to a teaching hospital in Ghana Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease 5(8) 658â??661.

- Ashikeni M A, Envuladu E A, Zoakah A I (2013) Perception and Practice of Malaria Prevention and Treatment among Mothers in Kuje Area Council of Federal Capital Territory Abuja Nigeria 2(3): 213-220.

- Babalola D A, Olarewaju M, Omeonu P E, Adefelu A O , Okeowo R (2013) Assessing the adoption of Roll Back Malaria Programme (RBMP) among women farmers in Ikorodu Local government area of Lagos state Canadian Journal of Pure and Applied Science 7 ( 2), 2375-2379.

- Bangirana P, Allebeck P, Boivin M, John C, Page C, Ehnvall A, Musisi S (2011) Cognition behavior and academic skills after cognitive rehabilitation in Ugandan children surviving severe malaria a randomized trial Biomedical Central Neurology.

- Bartoloni A, Zammarchi L, (2012) "Clinical aspects of uncomplicated and severe malariaâ?Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases 4 (1): e2012026.

- Beale J M, & Block J H, (2011) Wilson and Gisvoldâ??s textbook of organic medicinal and pharmaceutical chemistry 12th edition Philadelphia Lippincott Williams and Wilkins British National Formulary 2009 London BMJ group.

- Beer N, Ali A S, Eskilsson H, Jansson A, Abdul-Kadir F M, Rotllant-Estelrich G, Kallander K (2012) A qualitative study on caretakersâ?? perceived need of bed-nets after reduced malaria transmission in Zanzibar Tanzania BMC Public Health 12, 606.

- Borah Dhruba J and Sarma Sankara P (2012) Treatment seeking behavior of people with malaria and householdsâ?? expendicture incurred to it in a block in endemic area in Assam North East India BMC Infect Dis. 12 (Suppl 1): P41.

- Charles Ibiene Tobin-West e n k, (2016) Factors Influencing the Use of Malaria Prevention Methods Among Women of Reproductive Age in Peri-urban Communities of Port Harcourt City Nigeria.

- Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) (2011) National Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria FMOH National Malaria and Vector Control Division Abuja Nigeria.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2009) Strategic Plan 2009-2013 A Road Map for Malaria Control in Nigeria. Nigeria and National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) Abuja Nigeria.

- Halliday K E, Karanja P E, Turner L (2012) Plasmodium falciparum anaemia and cognitive and educational performance among school children in an area of moderate malaria transmission:baseline results of a cluster randomized trial on the coast of Kenya Trop Med Int Health 17(5): 532â??549.

- Han K M (2017) Malaria Prevention Practices Among Caregivers Of Children Under Five Years In Ingapu Township, Myanmar Banbkok: Mahidol University.

- Jombo Godwin, Araoye MA, Damen JG (2011) Malaria self medications and choice of drug for its treatment among residents of a malaria endemic community in West Africa Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease 1(1): 10-16.

- Mazigo H D O E, Mauka W, Manyiri P, Zinga M, Kweka E J, Mnyone L L, Heukelbach J, (2010) Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices about Malaria and its Control in Rural Northwest Tanzania Malar Res Treat 794261.

- MCEE (2015)MCEE-WHO methods and data sources for child causes of death Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/HIS/IER/GHE/2016.1.

- Medecins Sans Frontieres (2010) Clinical guidelines diagnosis and treatment manual for curative programmes in hospitals and dispensaries guidance for prescribing Janvier: Paris.135.

- Min S K (2014) Sai Khun M Malaria preventive behaviours among residents of Theinni Township Northern Shan State Myanmar Bangkok Mahidol University.

- Murray C J L, Rosenfeld L C, Lim S S, Andrews K G, Foreman K J, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez A D (2012) Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010 a systematic analysis Lancet 379:413â??431.

- Mutero C M, Schlodder D, Kabatereine N, Kramer R (2012) Intergrated vector management for malaria control in Uganda knowledge perceptions and policy development Malaria Journal 11(21):1-2.

- National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] (2012) National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) [Nigeria] and ICF International 2012 Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey 2010 Abuja Nigeria NPC NMCP and ICF International.

- (2010) National Population Commission National Malaria Control Programme ICF International Nigeria malaria indicator survey 2010 final report Abuja NPC NMCP ICF International.

- (2011)Nigeria Malaria Fact Sheet United states Embassy in Nigeria.

- Ogbonna C, Daboer J C, Chingle M P (2010) Knowledge and treatment practices of malaria among mothers and caregivers of children in an urban slum in Jos Nigeria Niger Med J 2010 9(2): 184-187.

- Okafor P I, Odeyemi K (2012) Use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets for children under five years in an urban area of Lagos State Nigeria Vol. 15.

- Okeke T A, Okeibunor J C (2010) Rural-urban differences in health-seeking for the treatment of childhood malaria in south-east Nigeria Health Policy 95:62-68.

- Olorunfemi E A, Adekoya G I (2013) Impact of health education on malaria prevention practices among nursing mothers in rural communities in Nigeria Niger Med J 2013 54 (2): 115-122.

- Oluwasogo AOI, Henry OSI, Abdulrasheed AA1 , Olawumi TA2, Olabisi EY1, (2015) Assessment of Motherâ??s knowledge and Attitude towards Malaria Management among Under Five Years Children in Okemesi-Ekiti Ekiti-West Local Government Ekiti State Estrjkl An open access journal, 5(2).

- Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Uzochukwu B, Ezeoke O, Eze S, Dike N (2010) Geographic inequalities in provision and utilisation of malaria treatment services in south-east Nigeria diagnosis providers and drugs Health Policy 94:144-149.

- Onyesom I, Onyemakonor N, (2011) Levels of parasitaemia and changes in some liver enzymes among malarial infected patients in Edo-Delta region of Nigeria Curr Res J Biol Sci 2011 3(2) 78-81.

- Opare J K L, (2013) Community Knowledge and Perceptions on Malaria and its Prevention and Control in the Akwapim North Municipality Ghana.

- Orimadegun A E, Ilesanmi K S (2015) Mothersâ?? understanding of childhood malaria and practices in rural communities of Ise-Orun, Nigeria implications for malaria control J Family Med Prim Care, 4(2), 226-231.

- Ouathara A F, Raso G, Edi C V A, Utzinger J, Tanner M, Dagnogo M, Koudou B G (2011) Malaria knowledge and long-lasting insecticidal net use in rural communities of central Cotedâ??voire Malaria Journal 10(288):1-6.

- Oyekale A S (2015) Assessment of Malawian mothersâ?? malaria knowledge healthcare preferences and timeliness of seeking fever treatments for children under five Int J Environ Res Public Health 12:521â??40.

- Romay-Barja M, Ncogo P, Nseng G, Santana-Morales M A, Herrador Z, Berzosa P, Benito A, (2016) Caregiversâ?? Malaria Knowledge Beliefs and Attitudes and Related Factors in the Beta District, Equatorial Guinea.

- Salihu Hamisu M, Diamond Elise, August Euna M, Rahman Shams, Mogos Mulubrhan F, Mbah Alfred K (2013) Maternal pregnancy weight gain and risk of placental abruption Nutrition Reviews 71:S1.

- Sato Y, Hliscs M, Dunst J, Goosmann C, Brinkmann V, Montagna GN (2016) Comparative Plasmodium gene overexpression reveals distinct perturbation of sporozoite transmission by profilin. Mol Biol Cell. 27:2234â??44.

- Uguru N P, Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BS, Igiliegbe G C, Eze S B (2009) Inequities in incidence morbidity and expenditures on prevention and treatment of malaria in southeast Nigeria BMC Int Health Hum Rights 9, 21.

- Ukaegbu C O, Nnachi A U, Mawak J D, Igwe C C (2014) Incidence of concurrent malaria and typhoid fever infection in febrile patients in Jos Plateau State Nigeria International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research 3(4):157â??161.

- UNICEF M (2012) Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development and UNICEF Situation Analysis of Children in Myanmar Nay Pyi Taw 2nd Edition Ed.

- UNICEF (2017) Child health Malaria mortality among children under five is concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa.

- United Nations Children Education Funds (2013) Use of longlasting insecticide treated bed nets 2013.

- Uzochukwu BS, Ezeoke OP, Emma-Ukaegbu U, Onwujekwe OE, Sibeudu FT, (2013) Malaria treatment services in Nigeria Nigerian medical journal 51 (4), 114-119.

- WHO (2014) World Malaria Report 2014 Geneva World Health Organization pp 32â??42. ISBN 978-92 4-156483-0.

- WHO (2017) World malaria report 2017 Geneva World Health Organisation Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- (2012) WHO Fact sheet on World Malaria report .

- (2015) WHO Nigeria Malaria profile.

- (2015) WHO, & UNICEF Achieving the Malaria MDG Target Reversing the Incidence of Malaria 2000â??2015.

- (2012) WHO Progress & impact series focus on Nigeria Country reports Number 4 Geneva WHO.

- (2014) WHO Factsheet on the world malaria report 2013.

- (2012) WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria World Health Organization.

- (2012) WHO Global technical strategy for malaria 2016-2030.

- (2015) WHO World Malaria Report 2015 Geneva WHO Press.

- (2016) WHO World Malaria Report 2016 Geneva World Health Organization.

- (2017) WHO World Health Organisation Fact Sheet Children reducing mortality Fact Sheet.

- (2017) WHO World Health Organisation Malaria in children under five.

- (2017e) WHO Treatment of Malaria.

- (2012) WHO Global Malaria Programme .World Malaria Report 2011 2012.

- (Mar, 2012) World Health Organization WHO Policy Recommendation Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) for Plasmodium falciparum malaria control in highly seasonal transmission areas of the Sahel sub-region in Africa.

- (2011) World Health Organization

- (2018) World malaria report Geneva World Health Organization.

- Yadav SP (2010) A study of treatment seeking behaviour for malaria and its management in febrile children in rural part of desert Rajasthan India J Vector Borne Dis ;47(4) 235-242.

- Young M, Wolfheim C, Marsh D R (2012) World Health Organization/ United Nations Childrenâ??s Fund joint statement on integrated community case management an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012 87 pp6â??10.

- Zewdie Birhanu Y Y (2017) Caretakersâ?? understanding of malaria use of insecticide treated net and care seeking-behaviour for febrile illness of their children in Ethiopia.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences