An Exploration of the Possibility of Utilizing Practice Based Evidence in Group Work with Disordered Gamblers in Singapore

Tan KTL*

Institute of Mental Health, National Addictions Management Service, Singapore

- *Corresponding Author:

- Tan KTL

Registered psychologist

Clinical Supervisor

Institute of Mental Health/National Addictions Management Service, Singapore

Tel: +48-3641-934706

E-mail: Lawrence1_@hotmail.com

Received Date: October 17, 2017; Accepted Date: November 06, 2017; Published Date: November 15, 2017

Citation: Tan KTL (2017) An Exploration of the Possibility of Utilizing Practice Based Evidence in Group Work with Disordered Gamblers in Singapore. Neurol Sci J Vol.1 No.1:8

Abstract

This paper examines the possibility and merits of utilizing assessment tools to facilitate candidate selection, measuring therapy process and tracking outcome measures for a short-term, time limited therapy group for patients diagnosed with a gambling disorder within a national addictions treatment facility in Singapore, the National Addictions Management Service (NAMS). NAMS is an addiction treatment and management center within a tertiary mental health facility. The center provides psychiatric and psychosocial treatment for patients struggling with both chemical and process addiction. In this particular context, we will be focusing on a group of patients with the diagnosis of gambling disorder.

Keywords

Addiction; Therapeutic; Therapy; Disorders; Education

The Context and Background

NAMS has been working with gambling patients in a group setting for the last ten years and the groups have evolved from a closed skills-based, psycho-education group that runs on a weekly basis to three different groups that meets the different and changing needs of help-seeking gamblers. The current groups that NAMS is running include:

(1) An 8 session open group for beginners (mainly psychoeducational and skills based) that is ran by an addictions counselor or an addictions trained psychologist;

(2) A semi-closed group (that is mainly supportive in nature and mimicking many elements of Gambler’s Anonymous Groups) that is ran by a peer specialist (usually a recovering gambler who has at least 2 years of “clean time”);

(3) An 8 session open family group for family members and supportive others of help-seeking gamblers.

The current configuration has been proven to be somewhat therapeutic and helpful based on the following observations and data:

1. Attendances to the groups have been encouraging. From a small number of attendees (an average of 4 members/session) when NAMS first 10 years ago, membership has grown to an average of 10-12 members/session in each of these groups.

2. Satisfaction surveys conducted for group attendees on a monthly basis have harvested fairly good outcomes as most patients (75% and above) have rated their group experiences as good to excellent.

3. Anecdotal feedback from patients (either solicited or voluntarily provided) was generally positive (some examples include, “I gained a lot from the groups, sometimes I don’t feel so alone when I hear others talk about experiencing problems that were very much like mine”, “It was helpful to learn from the circumstances of another member’s relapse without having to make those mistakes myself” and “There was great fellowship within the group, I also feel like I am betraying my fellow members in the group when I engage in behaviour’s and thoughts they were compatible with my gambling behaviour”).

The Problems and Limitations

It is easy to assume that NAMS is headed the correct direction if we simply focused on the above feedback and observations. However, there seems to be something missing as our assessments and evaluation of how well we are doing is solely dependent on satisfaction surveys, number of attendances and anecdotal feedback from group members. This hunch was further supported by Rousmaniere article highlighting that:

(1) Therapists operate largely in silos, sheltered from objective feedback and the most usual means of getting feedback is through the description/reflections of their recent clinical transactions with their supervisors (most of which may either be filtered, distorted or described from a subjective angle).

(2) Studies indicating that a high percentage of patients tend to "whitewash" their feedback to therapist, overstating the effectiveness of therapy and downplaying the intention to prematurely end therapy [1,2].

(3) The second issue relates to pre-group assessment and selection. Although there is a persuasive body of evidence indicating that proper pre-group assessment and selection of members has a lot of impact on how successful the group potentially can be this process is largely missing in NAMS since the beginning [3]. Selection of which patient is suitable or unsuitable for work group is mostly based on the clinical judgment of the intake counselor which is loosely based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

- Patient is open to share his/her issues in a group setting.

- Patient is reasonably motivated (assessed to be at least in the contemplative stage of change).

Exclusion criteria

- Patient struggles with severe social anxiety

- Patient is likely to be disruptive

- Patient highly resistant to being in a group

- Patient is floridly psychotic.

The problem with such a system is that it utilizes a set of loose criteria that relies heavily on the clinician's judgement at the point of assessment (which can sometimes be clouded by factors like personal biasness, social desirability of patients, issues of countertransference) without an objective and standardized tool to measure suitability. There is, definitely room to weave in a questionnaire, for example the Group Selection Questionnaire (GSQ) that measures a patient's potential suitability for group work during the intake session so as to pick up potential candidates for groups more accurately and to not set up unsuitable patients for failure and disillusionment [4].

The third issue in NAMS is the sense that there are no measures to specifically examine the process of change in group therapy. In short, there is no objective way (through the use of a standardized instrument) to look at important processes like how well members are working with one another, how connected or detached are people in the group or whether there was a sense of attunement and identification about what was going on between members. The only instance where this type of important process evaluation is done (in a somewhat disorganized and haphazard way) was the periodical checking in with group members about how they feel in the group and perhaps why they respond the way the respond to certain disclosures. This is problematic in a couple of ways. Firstly, as mentioned previous by Rousmaniere and also Asay, et al. [2,5], group members may express information on a questionnaire that they would otherwise not state verbally, particularly during the initial phases of therapy. Hence, having a questionnaire like the Group Climate Questionnaire (GCQ) or the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) may significantly increase the likelihood of discovering and addressing major process issues (e.g. empathetic failures, perception of being isolated in the group, anger with group leaders) more accurately and possibly in a much earlier stage, lowering the risk of premature attrition from group [6,7].

(4) The fourth issue, which is very much related to the second, is the fact that as an organization, NAMS only tracks attendance and patient satisfaction for group attending patients. The other outcome measures like addiction severity index and quality of life measure are tracked by the treatment monitoring team across all types of patients (both group attending and non-group attending ones) only giving the treatment team a general sense of how well help-seeking patients are progressing but not any idea about how much of these changes can be accounted for by being in a group. This situation is not ideal both for the group attending patient (as there would be no objective alignment between what they wanted from the group and what they would be getting in reality) and the administrators (on deciding whether it is economically viable to continue financing the groups or to pump more resources into the groups).

The Rationale for Starting a New Group

On top of wanting to assess the usefulness of objective tools in creating and running effective groups, NAMS is also in a good position to run a pilot group that is more process (rather than skill based or psycho-educational in nature). There is a generally sense that some addiction patients, beyond their immediate needs in recovery, would benefit from a deeper group that enables them to explore their interpersonal relationships so as to improve their satisfaction with relationships and subsequently the quality of their lives. Anecdotally, some patients verbalized about how their addictions is just a symptom of their deeper relational difficulties while others have talked about how they struggle with “fitting in” with people when they achieved longer recovery (beyond 3 months) and that their families (in a paradoxical way) were somehow able to cope with and manage them when they were active in addiction but struggle with relating to them when they are in recovery (the gambling almost becomes a tool/mechanism to mask their interpersonal difficulties and once it stopped, these difficulties become unravelled in its full glory).

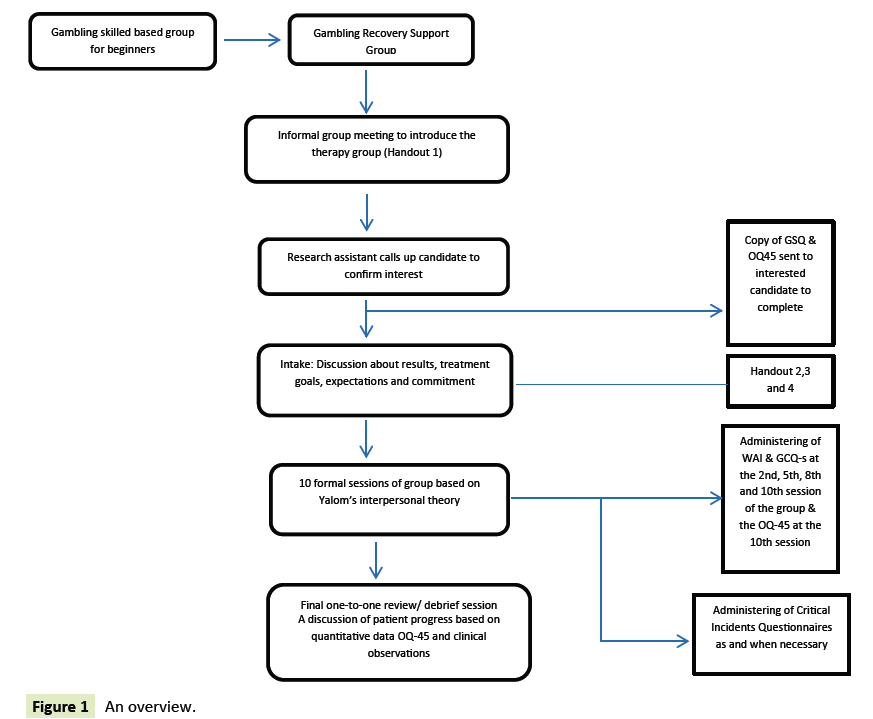

The Selection Process

The potential members for the group will be selected from the pool of members already attending the recovery support group. The advantage is that the members is in this group is stable in their recovery (most of them having achieved at least 6 months of total abstinence from gambling), is less likely to be preoccupied with early recovery issues (e.g. intense urges to gamble, preoccupation with a desperate financial situation that has not been managed) and has some experience of being in a group. These unique characteristics of members in the pre-existing recovery support group lower the likelihood of treatment failure and disillusionment when exposed to a process group. These will also be a group of recovering gamblers who verbalizes relational difficulties and dissatisfaction with life even after being free from gambling for a significant period of time.

An informal group session will be conducted with the members to explain the intention of starting up a process group and the nature of such a group. The handout 1 (presenting group therapy to clients) provided in the Core Battery-Revised an assessment tool kit for promoting optimal group selection, process and outcome will be utilized to better facilitate the process [8]. After which, a research assistant will call up these members individually to check on their interest in joining this new group. If they are agreeable, they will then be sent a copy of the GSQ and OQ45 to fill up and return to the treatment centre within a week. The returns of the GSQ and WIIP will be forwarded to an intake clinician (preferably one of the facilitators of the potential process group) to study before making an official appointment to see these candidates individually.

Although the Group therapy questionnaire is a more detailed measurement that can potentially harvest more information, the GSQ 3 is chosen for the purpose of screening and selecting potential group members because of the following reasons:

(1) It is easier and less taxing for the candidate to complete.

(2)The GSQ 3 is a valid and reliable tool for predicting a candidate's fit in the group.

(3) As the candidate is already an existing patient, a lot of the information is already available and can be crossed checked with the case records and the corresponding therapist that has worked with the candidate.

MacNair-Semands pointed out that the group therapy questionnaire (which takes over 45 minutes to complete) has only been effectively used in full clinical assessment on intake and hence the need for a shorter measure that can help clinicians to be more efficient and to prevent test taking fatigue [9]. During the face to face assessment session with the clinician, there will be a few objectives at hand. These objectives include:

(1) A discussion of the GSQ 3 and OQ 45 interpretation results. Here, there will be a triangulation of 3 main data points (background history of patient from clinical notes and therapist, impressions from the clinical observation in the here and now and the GSQ and OQ 45 results);

(2) An agreement on the problem area (treatment goals) that the candidate wants to work on;

(3) Clarification of any discrepancies. For example, if a person has endorsed the GSQ in a way that resulted a high score in demeanour issues while the clinical notes indicated very good success in previous skill based gambling that he has attended, the assessor may want to check in with the candidate. Similarly, if the same candidate appeared to be pleasant and receptive in the engagement with the assessor, the assessor can start a frank and open conversation about the discrepancies between the test results and clinical impressions.

(4) A decision to either include this candidate in the group or to make a more appropriate referral that may have a higher possibility of bringing about treatment success.

As the GSQ does not have any cut offs, it is difficult to immediately decide, based on the results, if a candidate is outright suitable or unstable for groups. Clearly, a high score, especially if it's consistently high on all subscales, raises alarm and the need to think about a more suitable referral. This is especially so if the data at hand matches the clinical observation in the here and now. For example, if candidate A scores a 20/25, 15/15 and 45/55 for the demeanor, expectancy and participation respectively and comes across as aloof, has a lot of demeaning remarks about the previous groups he attended, verbalizes that "he is keen to be in a group to prove the silly people who believes in talk therapy help wrong" may set the assessor thinking about whether A can benefit others or gain from being in a group. In addition to the GSQ, the selection guides for inclusion and exclusion (Burlingame [8]) and also be used in conjunction. If candidate B verbalizes interpersonal difficulties with his parents and romantic partners, has no psychosis, is positive about his previous group experiences in the gambling recovery support group, has a history of being compliant to both his individual and group

Treatment and is willing to commit to this new group, he/ she is likely to be someone suitable for the progress group. This is especially so if his GSQ 3 scores are relatively low and comes across as insightful and open to different kinds of group experiences (even if there can be times when he/she is placed in positions of discomfort).

The other questionnaire that the candidate would have filled up would be the OQ-45 (chosen because of its excellent psychometric properties and established norms and cut offs for dysfunctional symptoms). There are a few reasons for having them fill up this scale. Firstly, it would be used as a basis for discussion about the areas of dissatisfaction/dysfunction and the issues to focus on in treatment. Amongst the three subscales, the assessor will first look at the critical items like item 8 (suicide screening item), items 11, 26 and 32 (substance abuse items) and item 45 (violence at work item) and address accordingly if they are elevated (above 0). The advantage of NAMS being an addictive treatment centre and part of a larger psychiatric hospital, is the easy access to resources (for the purpose of referral) should the candidate demonstrate any significant difficulties in the abovementioned items. The assessor will also be particularly interested in discussing about the interpersonal relations subscales as the hypothesis is that the process group is most likely going to create positive changes in this scale and a huge bulk of the target symptoms will be derived from this scale. There can be a conversation in this session about the links between this subscale and the symptom distress subscale, i.e. how these issues (e.g. mood issues or even physiological discomfort) can be a direct or indirect symptom of an interpersonal pathology.

Secondly, the OQ-45 serves as an assessment to establish baselines and objectively track candidate progress throughout group therapy. It can also be used midpoint in group therapy to open up a discussion (if necessary) about self-report (self perception) of progress (as tracked by the OQ-45) versus the group's perception of the candidate's progress. For example, if a particular candidate has endorsed the OQ-45 as if he has made little to no progress (unreliable change of less than 14 point) or is still above the clinical cut off score of 63 after some work within the group has been done, the group therapist can follow up by looking at the process measures (which will be discussed later) and decide on the next course of intervention. This may entail an administration of a Critical Incidents Questionnaire (Burlingame [8]) in an attempt to examine if there were processes that were missed out or events that has disturbed the candidate/unsettled the candidate. Once it is decided that the candidate is suitable for group therapy, he/she will subsequently be given hangouts 2 (to be signed), 3 (for more information about groups to be gone through and discussed in the session) and 4 (confidentiality agreement to be signed).

Hypothetical example

Ramli, a 32-year-old male working as an accountant has highlighted his interest in being part of the process group after the informal session. Ramli came into the treatment centre 9 months ago for the management of his gambling related problems. He has managed to abstain from gambling completely after 2 months in treatment and has been a regular attendee of the skill based gambling group and the recovery support group. His score on the GSQ is 32 with his scores on each item mostly in the "1"s and "2"s region indicating that he is likely to benefit the group as well as gain from it. On the OQ45, Ramli scored 0 on the critical items and 60 in total. Although he has not hit the clinical dysfunction cut off, it is important to continue monitoring throughout the process of treatment as it is border line and close to the clinical cut off. In his three subscales, he scored 25, 25 and 10 for symptom distress, interpersonal relationship and social roles respectively. Based on this profile, the assessor started a conversation with Ramli about his concerns with social relationships and found that although Ramli managed to abstain from gambling for the past 7 months and has somewhat gotten a handle over his finances, he generally feels lonely and empty inside. He verbalized that although he feels proud of being able to stay in recovery, he feels a void left behind by gambling and can no longer "hide behind" machines or his computer indulging in online gambling and has to face his issue with getting along with people. Ramli says that he has difficulty making friends and people generally find him somewhat cold, aloof and uninterested. He feels he is deeply misunderstood and has a strong yearning to be connected with people just like anyone else. He added that he feels envious when he sees couples on dates and wish he has a partner. Ramli also mentioned that a few years ago he was in a relationship for half a year but it ended as his partner felt he lacked interest, made her feel unloved and cannot be bothered to sustain the passion and chemistry in their relationship.

Process Measures

The group (8-10 participants) conducted will be based on a brief version (10 sessions) of Yalom’s interpersonal group theory (Yalom [3]) where there is an underlying assumption about symptomatic difficulties being rooted in interpersonal psychopathological difficulties. Throughout the process, members will be encouraged to engage in horizontal disclosures, opening up and sharing about how they feel towards one another in the here and now and how they may be in a similar place in their own world outside the group (group being the microcosm of society). Yalom [3] mentioned about the feedback loop being a reinforcer of behaviour and will encourage more here and now processing where members can be constantly engaged to share about how it feels to get and give feedback to a fellow member. To facilitate this process, during the intake session, potential candidates would be engaged in a discussion about their treatment goals which can translate into transactions and behaviours in a group. For example, Ramli, during the intake, can collaboratively set some goals with the assessor about showing concern and interest to another member at least once in each group session and to elicit feedback from the recipient and the rest of the group about how it feels when Ramli does that. This process of inoculation, as coined by Whittingham [10] is considered a preventive intervention, whereby the therapist identifies a way of being (a pattern of behaviour) of the client that could negatively affect the client and/or the group and sets an initial goal for the client to experiment with a different way of interacting with others when they start the group [10].

To keep track of the above-mentioned processes and how an individual is doing in a group, some process measures will be utilized periodically. The first measure recommended to be used would be the working alliance Inventory (WAI) where the quality of collaborative relationship between the therapist and patient will be measured. The subscales within the WAI provide extremely important data for reflection and adjustment throughout the process of the group. For example, if a particular member scored lowly compared to the means of other members (e.g an individual mean of 1.75 compared to a group mean of 4.17) in the alliance scale after a couple of sessions in the group, it will be important to address the difference. Questions like, (1) whether the particular member perceives what the therapist’s interventions as helpful and relevant to his identified problems, (2) what seems to be missing or unhelpful, and (3) if there are rooms for adjustments and whether these adjustments prove helpful can also be assessed in future re-administering of the WAI. Similarly, the bond subscale within the WAI would also give a good sense of how much trust and acceptance is the member experiencing with the group facilitator. Very much like the data harvested from the alliance scale, these inputs from the member can be used positively to relook at certain interactional patterns and processes that may be missed out by the therapist during these sessions. Taken in all, charting and taking note of process changes through the group is instrumental in identifying the possibility treatment failures and the risk of losing the group member. The WAI is recommended to be administered periodically, on the 2nd, 5th, 8th and 10th session of this proposed group.

While the WAI looks at the quality of collaborative relationships between therapist and patient, there is a need for another instrument to objectively examine the relationships and sentiments of members towards the group they are in. The Group Climate Questionnaire- short form (GCQ-s) assesses members’ perception of climate within the group [11]. Like the WAI, the GCQ-s has 3 subscales which look at dimensions of engagement, avoidance and conflict. For example, if a group consistently scores highly in the avoidance subscale, i.e. a mean score of 4.86, which is significantly and substantially higher than the means established by Kivlighan and Goldfine [12] (2.16, 2.08 and 1.67 through the stages of engagement, differentiation and individuation), it may be helpful for the group facilitator to initiate a conversation with the group about their resistance to (1) take responsibility and ownership of their problems and (2) take risk to explore behaviours and getting into transactions (e.g confronting another member or expressing a differing opinion to what the majority of the group appears to endorse) that can feel somewhat uncomfortable [12]. This may also prompt the facilitator to explore the level of safety in the group and ways to enhance it so that members can gradually become more open to taking risks. Another example which may be cultural in nature is perhaps the absence of significant increase in the mean score of the conflict subscale during the differentiation phase of the group. This may not be a strange or abnormal phenomenon in an Asian population where members may work with conflict a little differently than their western counterparts. A third example could be the observation of an individual’s engagement scores plunging sharply after a session and the possibility of addressing this sudden drop in perceptions of cohesiveness and closeness within the group either individually or at the next group session. The GCQ-s is recommended to be administered periodically, on the 2nd, 5th, 8th and 10th session of the group. This brings us to the next process measure, the Critical Incidents Questionnaire.

The Critical Incidents Questionnaire could be used as and when the therapist deems appropriate as it is an extremely useful qualitative tool that can be used to examine group process as it can potentially harvest deeper information within a session as compared to the other 2 process measures. For example, if there is an important event happening in the group (if a member just made a huge disclosure about himself and many members seem to identify deeply with this disclosure or if a member, with much effort, manage to demonstrate a behaviour that is in line with his/her treatment goal), a Critical Incidents Questionnaire may be administered with members’ written inputs discussed in session. Similarly, as mentioned in the previous session, when an individual (or members) demonstrates a drastic plunge in his GCQ-s engagement score or a sharp rise in conflict/ avoidance scores, a Critical Incidents Questionnaire may also be administered to yield more information to help the therapist make better sense of and act on the observed phenomenon to prevent treatment failure, premature drop out or even more drastic consequences like the whole group collapsing.

Hypothetical case example

Ramli (the previously mentioned group member) comes across as a rather passive and laid back member of the group. In the second session, he rated the WAI alliance subscale and GCQ-s engagement subscales as 4.23 and 3.52 respectively, which were well within normative range and close to group averages. In the fifth session of the group when the 2 instruments were re-administered, Ramli's alliance and engagement subscales plunged to a 2.21 and 1.82 respectively. This was cause for concern for group facilitator which prompted him to ask the research assistant to send a Critical Incident Questionnaire for all members to fill up in before the sixth session so as to further examine what didn't go right for Ramli and how this possibly play out in the group. In the Critical Incident Questionnaire, Ramli wrote about how disengaged and isolated he felt from the group and that everyone seemed to connect well with one another and he seems to be the only odd one out. He mentioned a particular incident where the other members were giving him feedback about how insincere he sometimes sounds when he is comforting someone (as though he was reading from a script) and how disinterested he seem to be in another person's life. He also mentioned that the group seemed to disregard moments where he expressed concern for a fellow member and how disappointed he was when the group facilitator didn't take his side and be fair to him. He added that all this made him feel disconnected with the facilitator and the group which subsequently causes him to question about the relevance and effectiveness of attempting to resolve his issue via this group. He ended by saying it was difficult to verbalize this in the group as he fears further rejection and isolation. This led of an intervention by the facilitator in the beginning the next session by addressing Ramli's gripe about his experiences in the group. He started by highlighting that he understands Ramli may have a part of him that feels strongly about the stories that other people bring into the group. That were instances where he has attempted to express empathy but it seems like, from the previous sessions, other members still find him insincere and uninterested. He checks with the group by asking that what seems to be going on and if they genuinely feel that Ramli is basically and insincere person who cannot be interested in someone else's life. Some members begin to respond by first clarifying that they don't think he is insincere but it's more of the way he expressed his concern and how it comes across. Other members begin to acknowledge Ramli and verbalized that it must have been difficult for him and he was being sincere in his efforts (despite the outcome) to work on his issues and allowing himself to be put on the spot. Another member added that she sometimes admires Ramli for his "cool demeanor" and wishes that she can be so “chill” about things because she struggled with being over-familiar and lacked the capacity to curb her impulses to connect hastily and latch onto relationships that often end in disastrous ways. The facilitator then turned to Ramli and asked him how the feedback makes him feel and Ramli mentioned that he was relieved that the group acknowledge his efforts and was pleasantly surprised that someone actually was so accepting of him. The facilitator then invited Ramli to experiment with expressing concern to one of the group member in a different way (Figure 1).

Conclusion

As mentioned in the member selection section, the OQ-45 will be used as an outcomes measure (pre and post treatment) to track an individual’s overall progress after the completion of ten sessions. The outcomes of the OQ-45 will be revealed in the last, one-on-one review session with members individually. This will also be accompanied by individualized feedback based on the clinical observation of the group facilitator who has worked with the patient throughout the group therapy process. Hence both quantitative and qualitative feedback (together with future recommendations) will be presented to the patient [13].

First of all, the reviewer (the group facilitator) will need to take a look at the critical scales of the OQ-45 to ensure that there are no elevations at the end of groups. After which, the focus will be on whether there is reliable overall improvement (score changes by at least 14) and whether the new score has fallen below the clinically significant cut-off score of 63. For example, if a participant scores 68 as his baseline score and now has a score of 50 after being through the groups, he has achieved both reliable (score changes by 18) and clinical change (50 is below clinical cut off of 63). The mean of the improvements and the total score of all the group members can also be tabulated to look at whether the group, as a whole, has improved both reliably and clinically. The subscale scores can also be discussed in the session. For example, if the symptom distress score has fallen below 36 and by at least 10, it can be concluded that the patient has made realistic clinical progress in this area. In terms of the interpersonal relationship subscale, the patient’s score has to fall below 15 and by at least 8 to demonstrate realistic clinical progress. Using Ramli as an example, his score on this domain has to fall from 25 to 14 to be considered as having improved both clinically and reliably. Finally, the social role subscale has to fall below 12 and at least by 7 to indicate reliable clinical performance. In Ramli’s situation, his baseline social role dysfunction is below the clinical cut-off and the reviewer needs to take note if it elevates above the clinical cut-off after the group therapy ends. In addition, the reviewer can also compliment these quantitative score with qualitative feedback based the observations of the patient when he/she is in group therapy.

References

- Vahia NV (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 55: 220-223.

- Rousmaniere T (2017) What your therapist doesn’t know. The Atlantic Magazine.

- Yalom ID, Leszcz M (2005) The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

- Burlingame GM, Cox JC, Davies DR, Layne CM, Gleave R (2011) The Group Selection Questionnaire: Further refinements in group member selection. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 15: 60-74.

- Asay TP, Lambert MJ, Gregersen AT, Goates MK (2002) Using patient-focused research in evaluating treatment outcome in private practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology 58: 1213-1225.

- MacKenzie KR, Dies RR, Coche E, Rutan JS, Stone WN (1987) An analysis of AGPA Institute groups. International Journal of Group psychotherapy 37: 55-74.

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS (1989) Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36: 223-233.

- Burlingame GM (2006) CORE battery-revised: an assessment tool kit for promoting optimal group selection, process and outcome. New York: American Group Psychotherapy Association, USA.

- MacNair-Semands RR (2002) Predicting attendance and expectations for group psychotherapy. Group Dynamics: Theory Research and Practice 6: 219-228.

- Whittingham M (2011) Focused Brief Group Therapy: A practice-based evidence approach to group work in university counseling centers. Manuscript submitted for publication, p: 1129.

- MacKenzie KR, Dies RR (1983) The clinical application of a group climate measure. Advances in group psychotherapy: Integrating research and practice. New York: International Universities Press, pp: 159-170.

- Kivlighan DM, Goldfine DC (1991) Endorsement of therapeutic factors as a function of stage of group development and participant interpersonal attitudes. Journal of Counseling Psychology 38: 150-158.

- MacKenzie KR (1981) Measure of group climate. International Journal of Group psychotherapy 31: 287-296.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences