ISSN : 2348-9502

American Journal of Ethnomedicine

Ethnopharmacological Survey of Plants Used by Trado-Medical Practitioners (TMPs) in the Treatment of Typhoid Fever in Gomari Airport Ward, Jere Local Government Area, Borno State, Nigeria

1Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, College of Medical Sciences, University of Maiduguri, P.M.B. 1069, Maiduguri, Nigeria

2Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Jos, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- OA Sodipo

Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

College of Medical Sciences, University of Maiduguri

P.M.B. 1069, Maiduguri, Nigeria

E-mail: sodipoolufunke@yahoo.com

Abstract

Objective: The aim of the work was to carry out an ethnopharmacological survey of plants used by trado-medical practitioners (TMPs) in the treatment of typhoid fever in Gomari Airport Ward in Jere Local Government Area, Borno State.

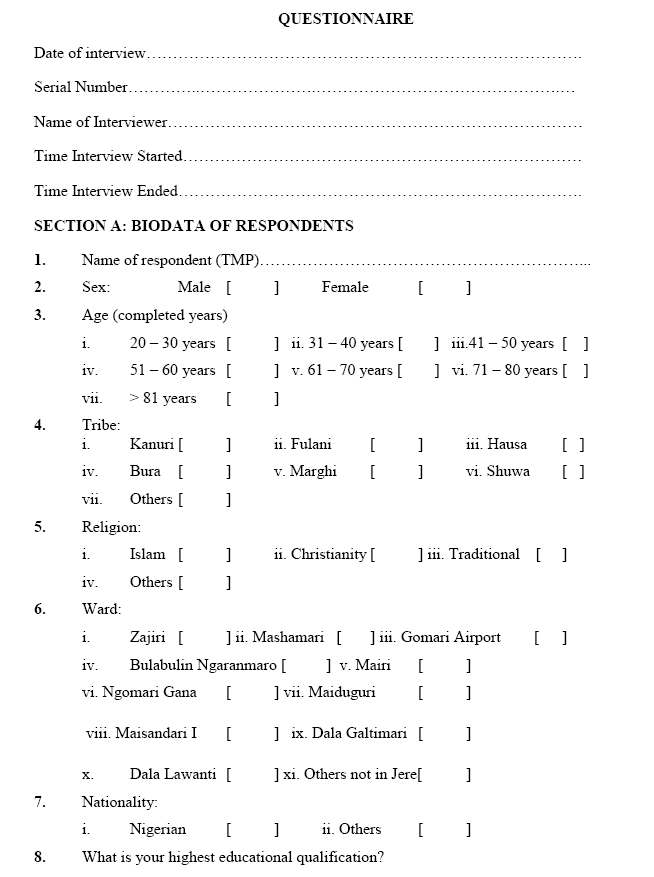

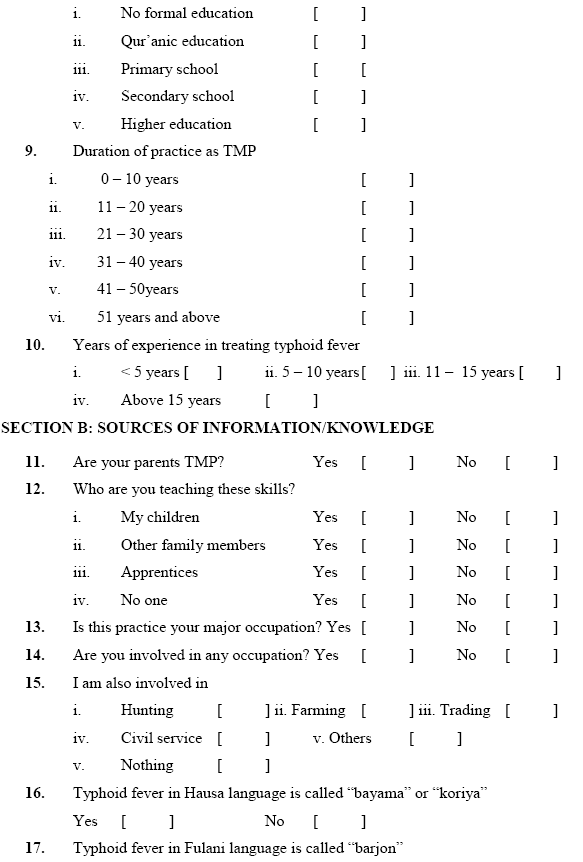

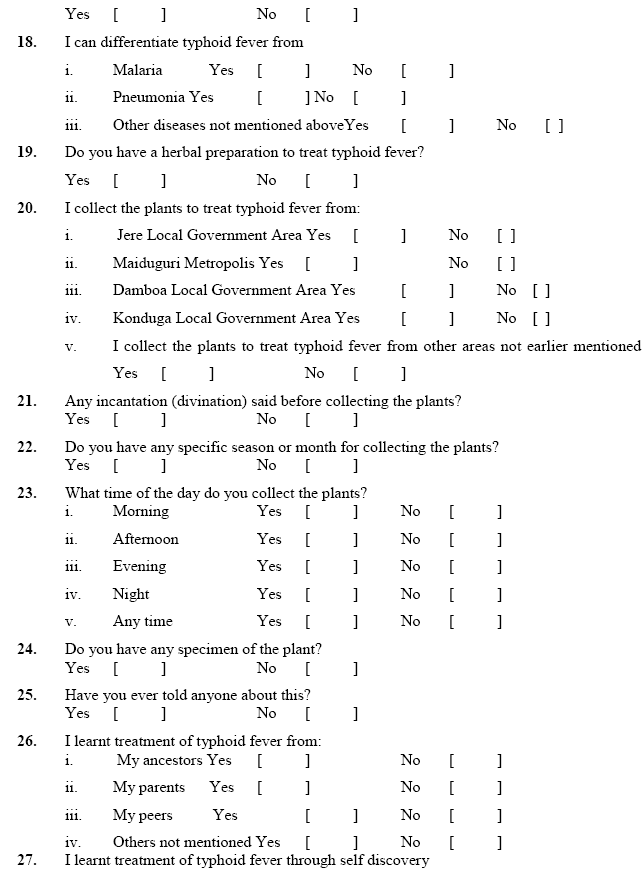

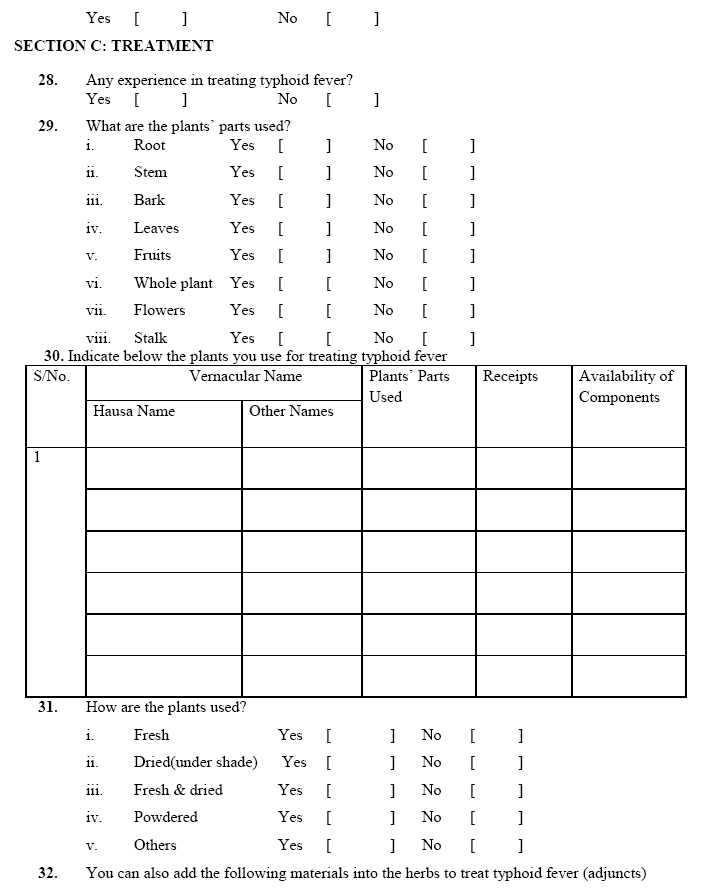

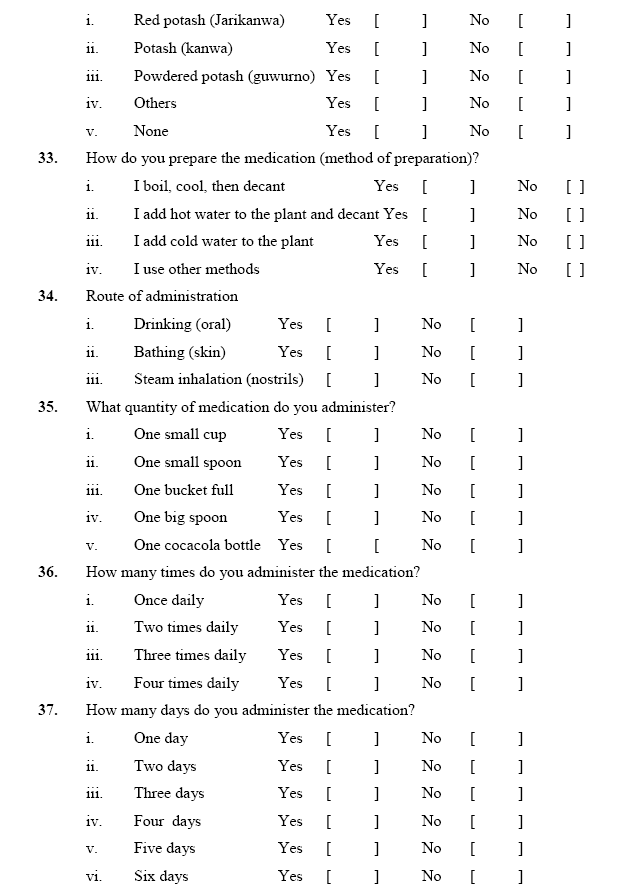

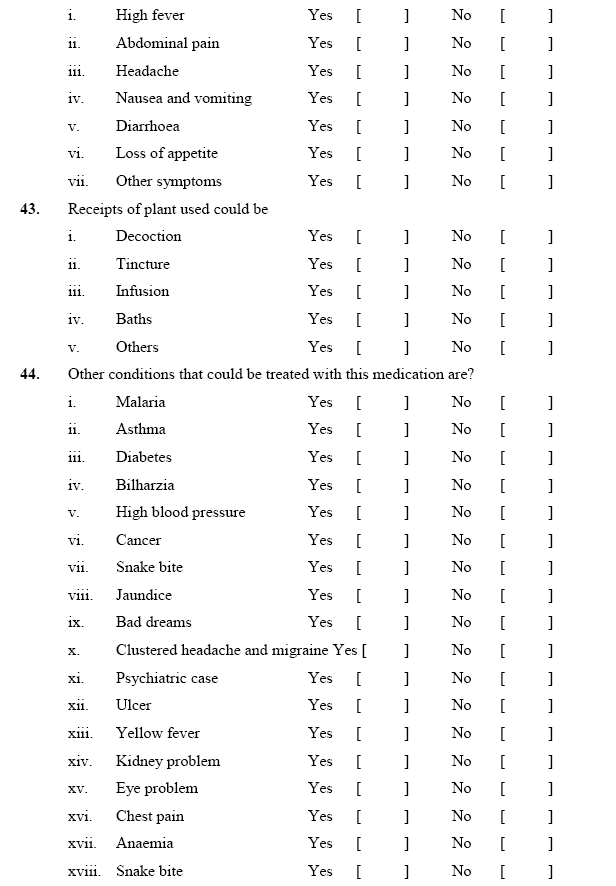

Methods: Ten (10) respondents (TMPs) were interviewed by primary data using pretested, validated and reliable 53-point structured questionnaire. The plants were identified and authenticated by a plant taxonomist and voucher specimens were prepared. Analysis of data was by cross sectional descriptive statistics.

Results: Results obtained showed that 22 plants from 18 families and 21 genera and 22 species were identified to cure salmonella infection. The family with the largest species was Caesalpinaceae (5 species). Trees were mostly used (41.67%) and the part of the plant used most frequently were the leaves (80.00%). Most TMPs had >15years experience in managing typhoid infection and many of the medicinal plant reipies involved a mixture of plants with only one (1) containing a single plant. Medications were mainly taken orally (90.00%) with 30.00% used as baths. Sometimes adjuncts were added to the plant.

Conclusion: Eventhough the efficacy of the remedies alluded to by the respondents cannot be calimed to be exact, the people used more herbal medicine than orthodox. This survey provides a template for further screening and research on these plants.

Keywords

Typhoid fever, Ethnopharmacological survey, Gomari airport, Tradomedical practitioners, Plants.

Introduction

Typhoid fever is a global infection [1] which is transmitted by eating food or taking water which is contaminated with the faeces of a person who is infected with and contain the bactirum, Salmonella enterica, Serovar typhi (often called Salmonella typhi) [2,3] The disease , apart from being a cause for concern is also a major public health issue in developing nations (like Asia and Africa), with Nigeria being of primary concern because of poor sanitary conditions and inadequate supply of water [4,5]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) there are six hundred thousand deaths from typhoid fever annually. [2,6,7] Also, an annual infection rate of 21.6 million was also estimated by WHO [6] with the highest percentage of these rates occurring in Africa and Asia. The large scale and indiscriminate use of antibiotics has led to microorganisms developing resistance, which is an adaptation system in which the microorganisms are no longer responding to drug concentrations to which they were previously susceptible. An unfortunate outcome of the large scale and indiscriminate use of antibiotics is the development of antimicrobial resistance as an adaptive response in which microorganisms begin to tolerate a concentration of drug to which it was previously susceptible. The development of mechanisms which circumvent or inactivate antibiotics is largely due to the versatility of the genes and the way the large number of micororganisms adapt. When plasmids coding for resistance to antibiotics are present in S. typhi, antibiotic resistance occurs. Allied to this issue of resistance is the transfer of plasmids which are resistant from one pathogen to another. Resistance has been observed to be carried out by one plasmid8. This plasmid belongs to incompatibility group H11 and is highly transmissible between similar pathogens. Recent reports suggest that S. typhi will have one of these plasmids which lead to resistance of antibiotics [9-11].

Antibiotic resistance in S. typhi is an emerging and important public health issue because those who use antibiotics to treat diseases are uncompromising in their behaviour. [12-14]. An outbreak in Tajikistan in the late 1990s, accounting for over 24,000 infections was caused by a multidrug resistance (MDR) S. typhi. [15]

A multidrug resistant (MDR) S. typhi strain that was not sensitive to chloramphyenicol and other first line recommended antibiotics like ampicillin and contrimoxaxole was discovered in many areas of Latin America Asia and Africa [14,16]. While there can be resistance to a single antibiotic, the occurrence of multi-drug resistance by this bacterium has worsened the health problems [17]. S. typhi is one of the most resistant organisms with multidrug resistant phenotype in S. typhi. [18] Resistant salmonella and infact other pathogens cause infections which lead to significant morbidity and mortality and make the healthcare cost to skyrocket worldwide. This study was therefore designed to document properly the plant flora that are used for treating typhoid fever by the indigenous people of Gomari Airport Ward in Jere Local Government Area of Borno State and to provide valuable information to encourage the conservation and sustainable utilization of plant wealth occurring in the area, which probably may reduce the cost of treatment. Also the occurrence of multidrug resistance to Salmonella typhi against antibiotics that are commonly used has brought about the need for new antimicrobial remedy from plant- derived medicines that are probably safer than synthetic ones. [3,19]

METHODS

Data collection

Primary data were used for collecting data from each respondent by administering pre-tested, validated and reliable 53 point structured questionnaire called the Instrument. The questionnaire comprised mainly close ended with a few open ended questions. Secondary data were sourced from journals and other periodicals, reference books, textbooks, internet search, library and monographs.

Design

The project was a cross sectional descriptive study. The survey was for four (4) months (19th November, 2013 – 1st March, 2014 = 21 days).

The present study was in Jere LGA, one out of the 27 LGAs in Borno State, Nigeria. It was carved out of Maiduguri Metropolitan Council (MMC) in 1996. [20] It occupies a landmass of 160km=2.21 Within the State, it shares boundaries with Mafa LGA to the east, MMC to the north and Konduga to the South. [22] The climate of Jere comprises cold and hot seasons and minimum temperature ranging from 15o- 20oC, while the maximum temperature ranges from 37o – 45oC. The rainfall is from 500mm to 700mm per annum [23].

Generally, there is a cool-dry season (October – February), hot season (March- June) and a short rainy (wet) season (June/July – September, October) with relative humidity which is low [24]. Generally, the topography is low land, plain and the soil is mostly sandy with short grasses and thorny shrubs. [25,26] There are ten (10) wards in Jere LGA; LGA; this study was carried out in Gomari Airport Ward.

Population/Sample

The population of the registered TMPs in Borno State is not known. [27] However, what remains clear according to the Ministry of Health, is that there is no list of registered TMPs in Borno State bringing all the TMPs together under one umbrella (i.e. there was no sampling frame of TMPs) in the recent past (1-3years) Based on this, a multistage sampling was used to select 10 TMPs in the study area i.e. Gomari Airport Ward using random sampling (balloting).

The plants were identified and authenticated by a plant Taxonomist at the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Maiduguri.

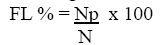

The fidelity level (FL) in % was also calculated to compare data from the study area on plants that are often used. It was calculated using the formula:

Where:

FL % = Fidelity level

Np = No. of TMPs that claim the use of a plant for the treatment of typhoid fever (No. of citations of each plant)

N = Total No. of TMPs in the study area. Source: Adapted from [28,29]

Data analysis

The information obtained from the questionnaire were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as tables, percentage and frequency distribution tables to evaluate the practice of TMPs in the study area. Correlation was assessed by Pearson Test using SPSS version 16.0 of 2007 for all computations.

RESULTS

Validity and reliability of the instrument (Questionnaire)

The validity of the instrument was high and the reliability according to Pearson correlation coefficient (r) also called Cronbach alpha (α) at the end of the study was found to be 0.896.

Plant species, botanical names and local names

A total of twenty two (22) plants belonging to 18 families, 21 genera and 22 species were identified to be used in the treatment of typhoid fever in the study area (Table 1). Their botanical names, families, parts used, their preparation, dosage and administration are shown in Table 1. The family with the largest number of plant species was Caesalpiniaceae (with 5 species). The remaining 17 families had 1 specie each.

Table 1. Medicinal plant, name, family, part used and availability of plant in treatment of typhoid fever in Gomari Airport Ward, Jere Local Government

| S. No. | Botanical name and family | Part Used | Common name | Vernacular name | Availability of plant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cassia occidentalis Linn. (Caesalpiniaceae) | Leaves (Fresh ) Whole plant (fresh except root) | Negro coffee, stinking weed | Rai daure, majanzafari (Hausa); Rere (Yoruba); Okidiagbara (Igbo) | Jere LGA (Unimaid), MMC |

| 2. | Azadirachta indica A. Juss (Meliaceae) |

Leaves (fresh) | Neem tree | Dogo yaro, darbejiya (Hausa); Amuka (Yoruba); Okwuru- ozo (Igbo) | Jere LGA (Unimaid), MMC |

| 3. | Citrus aurantifolia Christm = C. limon (L.) Burm. F. Swing (Rutaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Orange (Lime) | Lemun tsami (Hausa); Osan wewe (Yoruba); Olome, Oroma nkilisi (Igbo) | Jere LGA (Unimaid) MMC |

| 4. | Sterospermum kuthianum Cham. (Bignoniaceae) | Stem bark (dried) | Nil | Sansami (Hausa) | Mafa LGA |

| 5. | Erythrina senegalensis DC = Chirocalyx latifolia; Erythrina latifolia (Papilionaceae) | Stem bark (dried) | Coral tree, coral flower | Mirjinya, Faskara giwa (Hausa); Ologunsese (Yoruba); Echichi; echichili (Igbo) | Damboa LGA |

| 6. | Cochlospermum tinctorium A. Rich (Cochlospermaceae) | Root (dried) | Nil | Rawaya (Hausa); Rawaye (Yoruba); Nkalike, Obasi (Igbo) | Konduga LGA |

| 7. | Hygrophilia auriculata (Schumach) Heine (Acanthaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Talmak-hana | Zazargiwa, Kayar rakumi (Hausa); Zanagodoye (Kanuri) | MMC(Zoo) |

| S. No. | Botanical name and family |

Part Used | Common name |

Vernacular name | Availability of plant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8. | Tamarindus indica L. (Caesalpiniaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Tamarind, Indian nut; | Tsamiya (Hausa); Tamshu (Kanuri); Nbula (Babur); Icheku oyibo (Igbo); Ajagbon (Yoruba) | Jere (Unimaid), MMC |

| 9. | Asparagus africanus Lam. (Liliaceae) |

Whole plant (dried) | Nil | Mugamu adawa (Hausa); Aluki, Kaadan, Koobe (Yoruba) |

|

| 10. | Acacia albida Del. (Mimosaceae) | Leaves (fresh or dried) | Nil | Gawo (Hausa); Karau (Kanuri); Kad’ha (Babur) | Jere (Unimaid) |

| 11. | Veronia amygdalina (Wild) Darke (Asteraceae) | Leaves (fresh or dried) | Bitter leaf | Shiwaka (Hausa); Ewuro (Yoruba); Onugbu; Olugbu (Igbo); Kiriologbo (Ijaw) Onugbu (Urhobo) |

Jere (Unimaid) |

| 12. | Waltheria americana L. (Sterculiaceae) | Roots (dried) | Nil | Hankufa (Hausa); Korikodi, Opa-emere (Yoruba) | Jere LGA (Unimaid), MMC |

| 13. | Boswellia dalzielli Hutch (Burseraceae) | Roots (dried) | Frankin-cense tree | Ararrabi (Hausa); Kaafidafi, Dikkwar (Kanuri); Deburo (Babur) | Damboa LGA Biu LGA |

| 14. | Cassia singuena Del. (JLG/07) (Caesalpiniaceae) |

Roots (fresh) | Nil | Rumfu (Hausa); Fanalewa (Kanuri); Bag’sha (Badur) | MMC |

| 15. | Cordia africana Lam. (Boraginaceae) | Stem bark (fresh) | Nil | Alulluba (Hausa); Alwa (Kanuri); Alwa (Babur) | Yobe State |

| S. No. | Botanical name and family | Part Used | Common name | Vernacular name | Availability of plant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16. | Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell. (Celastraceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Nil | Bakororo, namijin tsada (Hausa); Karau karau (Kanuri); Soofi (Babur); Sepolotiun (Yoruba) | MMC, Jere, |

| 17. | Celtis integrifolia Lam. (Ulmaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Nil | Zuwo (Hausa); Nguzo (Kanuri); Nguzo (Babur) | MMC |

| 18. | Combretum glutinosum Pers. Ex DC (Combretaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Nil | Kattakara, taranniyi, farin ganya (Hausa); Kadaar (Kanuri); Shafa (Babur) | Jere (Unimaid) MMC |

| 19. | Pilostigma reticulatum (DC) Hochst CAESALPINIACEAE | Root (fresh) | Pilostigma | Kargo, kalgo (Hausa); Kalur (Kanuri); B’ula (Babur); Abafe, Abafin (Yoruba) | Jere (Unimaid), MMC, |

| 20. | Cadaba farinosa Forssk (Capparidaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Nil | Bagayi (Hausa); Marra (Kanuri); Marka (Babur) | MMC |

| 21. | Gossypium herbaceum L. (Malvaceae) | Leaves (fresh) | Cotton | Auduga (Hauda); Kaitan (Kanuri); Owu (Igbo); Laghosa (Yoruba) | Jere (Unimaid) |

| 22. | Detarium microcarpum Guill ex Perr. (Caesalpiniaceae) | Root (fresh) | Taura (Hausa); Ogbogbo, sedun (Yoruba); Ofo (Igbo) | Biu LGA |

MMC Maiduguri Metropolitan Council Unimaid University of Maiduguri

LGA Local Government Area

| Number of families | = | 18 |

| Number of genera | = | 21 |

| Number of species | = | 22 |

Most of the medications used involved a mixture of plants with one treated with only a single plant (Table 2). One TMP used only the dried leaves and bark of Pilostigma reticulatum, boiled, cooled then decanted and it was taken and also used as bath.

Table 2. Medicinal plants recipe, part used, method of preparation, dosage, added substances (adjunct), mode of administration, precaution, side effects, receipts and other uses

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of prepa- ration | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cassia occidentalis L. | Leaves (fresh) | Boil the plants together with potash (kanwa), Cool then decant | Take one small cup three times daily for three days, cover the body with the remaining and inhale | Potash (Kanwa) | Decoction | Oral, inhalation | None | None | None |

| + | ||||||||||

| Azadirichta indica A. Juss |

Leaves (fresh) |

|||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Citrus aurantifolia Christm. |

Fruit (fresh) |

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of preparation | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pound the dried | Take one | |||||||||

| 2. | Sterospermum kuthianum Cham | Stem bark (dried) | plant into powder, boil with red potash (jarikanwa), allowto cool thendecant |

small cup two or three times daily for five days. Repeatafter five daysif patient is |

Red potash (jarikan-wa) | Decoction | Oral | Do not give on an empty stomach | Diz- ziness | None |

| not cured | ||||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Erythrina senegalensis | Stem bark (dried) |

|||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Cochlospermum tinctorium A. Rich |

Root (dried) |

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of preparation | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3. | Cassia occidentalis Linn. |

Leaves (Fresh ) | Boil the three leaves together, cool, then decant | Take as tea (one small cup) twice daily for three days | None | Decoc- tion | Oral | Do not give on an empty stomach | Urine color- ation and dizzi- ness |

None |

| + | ||||||||||

| Hygrophilia auriculata (Schumach) Heine |

Leaves (fresh) | |||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Tamarindus indica L. |

Leaves (fresh) |

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of preparation | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Take one small | ||||||||||

| Asparagus | Whole | Pound the | spoon full two | |||||||

| 4. | africanus Lam. | plant | dried shrub | times daily with | None | Powder | Oral | None | None | None |

| (dried) | into powder | milk for three | ||||||||

| days | ||||||||||

| Detarium | ||||||||||

| microcarpum et. | bath with it twice | |||||||||

| Perr. Guill | Root | Boil the three | daily for five days, | |||||||

| 5. | (fresh or | plants together | also inhale the | None | Baths | Skin, inhalation | None | None | Malaria | |

| dried) | after pounding | steam twice daily | ||||||||

| for five days | ||||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Acacia albida Del. | Leaves (fresh or dried) |

|||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Veronia amygdalina (Wild) Darke |

Leaves (fresh or dried) |

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of preparation | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6a. | Pilostigma reticulatum (DC) Hochst | Leaves &bark (dried) | Boil the dried leaves and bark together in water, cool then decant | Take one small cup twice daily, also bath with it for three | None | Baths, decoc- tion | Skin, oral | None | None | Malaria |

| days | ||||||||||

| 6b. | Waltheria americana L. + | Roots (dried) | Boil the two roots together with red potash (jarikanwa), cool then decant | Drink one cup three times daily for seven days | Red potash (jarikanwa) | Decoc- tion | Oral | None | Urine colorati on | Malaria |

| Boswellia dalzielli | Roots (dried) |

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of preparation | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cassia | Boil the two | |||||||||

| occidentalis Linn. | plants together | Drink one | ||||||||

| 7. | Leaves (Fresh ) |

after cutting into pieces with red potash |

small cup three times daily for one |

Red potash (jarikanwa) | Decoction | Oral | None | None | None | |

| + | (jarikanwa), cool | week | ||||||||

| then decant | ||||||||||

| Cassia singuena Del. |

Roots (fresh) |

|||||||||

| 8 | Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell. | Leaves (fresh) | Boil the two plants together the red potash (Jari kanwa) | Take one small three times daily after eating for three | Red potash (jarikanwa) | Decoction | Oral | Not to be taken on an empty stomach | Urine colorati on | High blood pressure |

| + | days | |||||||||

| Cordia africana Lam. |

Stem bark (fresh) |

| S. No. | Medicinal plant recipe | Part used | Method of preparation | Dosage | Added substance (adjunct) | Receipt of recipe | Mode of administration |

Precaution | Side effect | Other uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celtis integrifolia Lam |

Boil the three | Drink one small cup two | Clustered | |||||||

| 9. | Leaves (fresh) |

plants together, cool, |

times daily, also bath with |

None | Baths, Decoction |

Oral, skin | None | None | head ache and |

|

| then decant | it twice daily | migraine | ||||||||

| + | for one week | |||||||||

| Combretum glutinosum Pers. Ex DC |

Leaves (fresh) | |||||||||

| + | ||||||||||

| Pilostigma reticulatum (DC) Hochst |

Root (fresh) | |||||||||

| 10. | Cadaba farinosa Forssk |

Leaves (fresh) | Boil the two plants together in a bottle of cocacola water with red | Drink all the content daily for three days | red potash (jarikanwa) | Decoction | Oral | None | Urine colo- ration | Cancer |

| + | potash (jarikanwa) |

|||||||||

| Gossypium herbaceum L. |

Leaves (fresh) |

KEY: One big spoonful = 15 ml; One small cup = 30-40 ml; One cocacola bottle =75 ml; One sachet of water = 500 ml.

Fidelity Level (FL)

Cassia occidentalis Linn. (Caesalpinaceae) is the specie with the highest FL (40.00%) as shown in Table 3. All the other plants had FL of 10.00% each.

Table 3. Fidelity level (FL) among TMPs in Gomari Airport Ward, Jere LGA on the most reported plants used in the treatment of typhoid fever

| S. No. | Plant used | Family | Fidelity level (FL) % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cassia singuena Del. | CAESALPINACEAE | 10.00 |

| 2. | Cassia occidentalis Linn. | CAESALPINACEAE | 40.00 |

| 3. | Tamarindus indica L. | CAESALPINACEAE | 10.00 |

| 4. | Sterospermum kuthianum Cham. | BIGNONIACEAE | 10.00 |

| 5. | Asparagus africanus Lam. | LILIACEAE | 10.00 |

| 6. | Citrus aurantifolia Christm. | RUTACEAE | 10.00 |

FL % = Np x 100

N

where: Np = No. of TMPs that claim the use of a plant for the treatment of typhoid fever (No. of citations).

N = Total No. of TMPs in the study area (10).

[Source: Adapted from (28); (29)]

FL is done to compare data from the study area on plants that are often used.

Habitat and status of species

Most of the plants used are trees (41.67 %), followed by shrubs (25.00 %), herbs (16.67 %) under shrub and bushy plant (8.33 % each) [Table 4] spread across Gomari Airport ward in the LGA.

Table 4. Habitat of the medicinal plants used in the treatment of typhoid fever in Gomari Airport Ward, Jere Local Government Area

| S. No. | Growth Habitat | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Grass | - | - |

| 2. | Tree | 5 | 41.67 |

| 3. | Aquatic plant | - | - |

| 4. | Bushy plant | 1 | 8.33 |

| 5. | Parasite | - | - |

| 6. | Weed | - | - |

| 7. | Shrub or small tree | 3 | 25.00 |

| 8. | Climber or liana | - | - |

| 9. | Herb | 2 | 16.67 |

| 10. | Thickets | - | - |

| 11. | Shrubby weed | - | - |

| 12. | Under shrub | 1 | 8.33 |

| Total | 12 | 100.00 |

Socioeconomic characteristics/demographic Data of TMPs

The study revealed that most of the TMPs were men (90.00 %) whilst 10.00 % were women (Tables 5).

Table 5. Biodata of respondents or (Demographic Data of TMPs)

| S. No. | Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sex: | Male Female |

09 01 |

90.00 10.00 |

| < 50 | 01 | 10.00 | ||

| 51-60 | 02 | 20.00 | ||

| 2. | Age in year | 61-70 | 03 | 30.00 |

| 71-80 | 02 | 20.00 | ||

| > 81 | 02 | 20.00 | ||

| Kanuri | 03 | 30.00 | ||

| Fulani | 03 | 30.00 | ||

| Hausa | 01 | 10.00 | ||

| 3. | Tribe | Bura | 01 | 10.00 |

| Marghi | 00 | 00.00 | ||

| Shuwa | 00 | 00.00 | ||

| Others | 02 | 20.00 | ||

| 4. | Religion | Islam Christianity Traditional Others | 10 00 00 00 |

100.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

| 5. | Nationality | Nigerian Others | 10 00 |

100.00 0.00 |

| 6. | Educational qualification | No formal education Quaranic education Primary education Secondary education Higher education | 00 08 00 02 00 |

0.00 80.00 0.00 20.00 0.00 |

| 7. | Duration of practice of TMP | 0-10yrs 11-20yrs 21-30yrs 31-40yrs 41-50yrs 51yrs and above |

00 02 01 02 02 03 |

0.00 20.00 10.00 20.00 20.00 30.00 |

| 8. | Years of experience in treating typhoid fever | < 10 years 11-15yrs Above 15yrs |

00 01 09 |

0.00 10.00 90.00 |

Key:

n = Total No. of TMPs = 10

TMP = Trado-medical practitioner

Sources of information/knowledge

All the TMPs’ parents were tradomedical practitioners themselves (100.00 %) as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Sources of information/knowledge on typhoid fever

| S. No. | Statement | Yes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | |||

| 1. | My parents are TMP | 10 | 100.00 | |

| 2. | Those being taught the skill by me | My children Other family members Apprentices No one |

06 02 06 02 |

60.00 20.00 60.00 20.00 |

| 3. | The practice is my major occupation |

10 | 100.00 | |

| 4. | I am involved in another occupation |

03 | 30.00 | |

| 5. | I am also involved in | Hunting Farming Trading Civil service Others Nothing |

03 00 00 00 00 07 |

30.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 70.00 |

| 6. | “Bayama” or “koriya” is Hausa name for typhoid fever |

0 | 0.00 | |

| 7. | “Barjon” is Fulani name for typhoid fever |

0 | 0.00 | |

| 8. | I can differentiate typhoid fever from | Malaria Pneumonia Other diseases not mentioned above |

10 10 10 |

100.0 100.00 100.00 |

| 9. | I have a herbal preparation to treat typhoid fever |

Yes | 10 | 100.00 |

| 10. | Area of collection of the plants | Jere LGA MMC Damboa LGA Konduga LGA Other areas not earlier mentioned |

07 06 02 01 06 |

70.00 60.00 20.00 10.00 60.00 |

| S. No. | Statement | Yes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | |||

| 11. | Incantation (divinations said before collecting the plant) |

0 | 0.00 | |

| 12. | Special season or month for collecting the plants |

0 | 0.00 | |

| 13. | Time of the day for collecting plant | Morning Afternoon Evening Night Anytime | 0 0 0 0 10 |

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 100.00 |

| 14. | I have specimen of the plant | 10 | 100.00 | |

| 15. | I have told someone about the plant |

10 | 100.00 | |

| 16. | I learnt treatment of typhoid fever from | My ancestors My parents My peers Others not mentioned |

05 04 01 0 |

50.00 40.00 10.00 0.00 |

| 17. | I learnt treatment of typhoid fever through self discovery |

0 | 0.00 | |

Key: n = No of respondents (TMPs) = 10 TMP = Trado-medical practitioner f = frequency

% = percentage

MMC = Maiduguri metropolitan council

Plant Parts, How Used and Obtained

Leaves are the part of the plants most frequently used (80.00 %), followed by the root (50.00 %), bark (20.00) and whole plant (10.00) as shown in Tables 8.

Table 7. Treatment of Typhoid fever in Gomari Airport Ward

| S. No. | Statement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | ||||

| 1. | Experience got in treating typhoid fever |

10 | 100.00 | |

| 2. | Plant parts used | Root Stem Bark Leaves Whole plant |

05 01 02 08 01 |

50.00 10.00 20.00 80.00 10.00 |

| 3. | How plant parts are used | Fresh Dried (under shade) Fresh &dried |

06 02 02 |

60.00 20.00 20.00 |

| 4. | Adjuncts added | Red potash (Jarikanwa) Potash (kanwa) None |

05 02 04 |

50.00 20.00 40.00 |

| 5. | Method of preparation of medication | Boil, cool, then decant Add cold water to the plant and decant |

09 01 |

90.00 10.00 |

| 6. | Route of administration | Drinking (oral) Bathing (skin) Steam inhalation (nostrils) |

09 03 02 |

90.00 30.00 20.00 |

| 7. | Quantity of medication administered | One small cup One small spoon One bucket full One big spoon One cocacola bottle |

08 00 03 00 01 |

80.00 0.00 30.00 0.00 10.00 |

| 8. | Number of times medication is administered |

Once daily Twice daily Three times daily |

01 06 05 |

10.00 60.00 50.00 |

| 9. | No. of days medication is administered for | One day Two days Three days Four days Five days Six days Seven days |

0 0 06 0 02 0 03 |

0.00 0.00 60.00 0.00 20.00 0.00 30.00 |

| 10. | Duration of treatment | Less than one week One week Two weeks Three weeks Four weeks |

08 03 0 0 0 |

80.00 30.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

| 11. | Powdered medication is taken with the following | Milk Nothing | 01 09 |

10.00 90.00 |

| S. No. | Statement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||

| 12. | Precaution taken | Not given on an empty stomach No precaution taken |

03 07 | 30.00 70.00 |

| Herbal alone | 100.00 | |||

| Herbal and | 10 | 0.00 | ||

| divination | 0 | |||

| 13. | Method of treatment | Herbal and diet | 0.00 | |

| Divination | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| (incantation) | 0 | |||

| alone | ||||

| High fever | 10 | 100.00 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| 14. | Basis of treating typhoid fever on diagnosis | Headache Nausea and vomiting |

10 0 |

100.00 0.00 |

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Loss of appetite | 10 | 100.00 | ||

| Decoction | 07 | 70.00 | ||

| Tincture | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| 15. | Receipts of plants used | Infusion | 0 | 0.00 |

| Baths | 03 | 30.00 | ||

| Others | 01 | 10.00 | ||

| Malaria | 02 | 20.00 | ||

| High blood | 01 | 10.00 | ||

| pressure | ||||

| 16. | Other conditions that could be treated with the medication |

Cancer Clustered |

01 01 |

10.00 10.00 |

| headache and | ||||

| migraine | ||||

| None | 05 | 50.00 | ||

| 17. | Treatment is taken in isolation | 10 | 100.00 | |

| No charge at all | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| 18. | Cost of treatment | No charges only appreciation |

09 | 90.00 |

| *Charges | 01 | 10.00 | ||

Key: n = No of respondents (TMPs) = 10 TMP = Trado-medical practitioners f= frequency

% = percentage

*N10,000.00

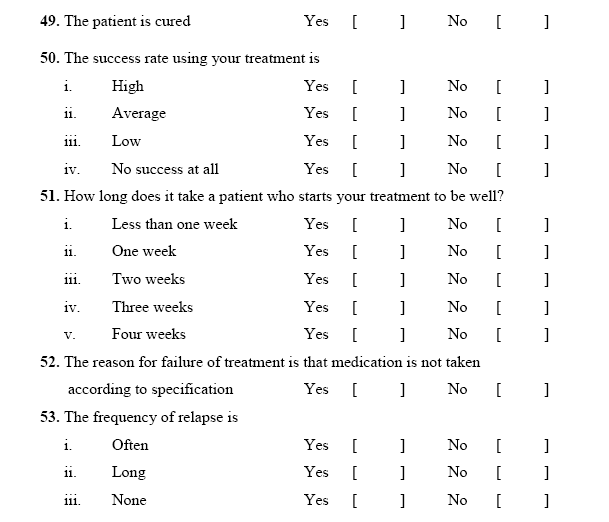

Table 8. Evaluation of treatment of typhoid fever

| S. No. | Statement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Side effects | Urine colouration Dizziness Skin rashes Sedation Frequent urination Profuse sweating None |

04 02 00 00 00 00 05 |

40.00 20.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 50.00 |

| 2. | Effect of herbs on patients | Fever disappears Headache disappears Appetite improves |

10 10 09 |

100.00 100.00 90.00 |

| 3. | Patient is cured | 10 | 100.00 | |

| 4. | Success rate | High Average Low |

10 0 0 |

100.00 0.00 0.00 |

| 5. | Time it takes patient to be well |

Less than one week One week |

07 03 |

70.00 30.00 |

| 6. | Treatment failure occurs if medication is not taken according to specification | 10 | 100.00 | |

| 7. | Frequency of relapse | Often Long None |

0 0 10 |

0.00 0.00 100.00 |

Key: n = No of respondents (TMPs) = 10 f = frequency

% = percentage

Treatment of typhoid fever, dosages and treatment evaluation

All the TMPs (100 %) had experience in treating typhoid fever. The medications were mainly taken orally (90.00 %), with 30.00 % being applied as baths on the skin and 20.00 % used through inhalation (Table 8) but some applications were prepared from a mixture of plants or ingredients such as milk, (10.00 %).

The reported adverse effects included urine colouration (40,00 %) and dizziness (20.00%) as shown in Table 8. All the TMPs claimed that evidence of treatment was that headache and fever disappeared whilst 90.00% reported that appetite improved. In addition 100% of them reported a high cure rate of typhoid fever and 70.00% of the patients were well in less than 1 week and the remaining 30.00% fully recovered in one week. Treatment failure only occurred if medication was not taken according to specification and no frequency of relapse was reported.

DISCUSSION

The validity of the instrument was high indicating the appropriateness of interpretation made from the results of the questionnaire, according to the context of the instrument as set out in the objectives of the survey and not merely on superficial examination. [30-32]

The result of this survey in which 22 plants were identified is comparable to the result obtained when an ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the treatment of typhoid fever by the Idoma people of Nigeria was carried out where a total of 21 species belonging to 18 plant families were identified [2]. These species are known plants used as medicine in North East Nigeria [34] and all of them were widely used by the TMPs in Gomari Airport Ward in Jere Local Government Area, Borno State.

In this study area, the use of traditional medicine is widely accepted. This is evident from the number of plant species (22 plants) identified as medicinal. Through the plants identified as medicinal plants species are few compared with 96 medicinal plants identified in Enugu State, Nigeria by [35]; 129 plants in Bolivia by Macia et al.(2005) but more compared with 45 medicinal species identified by [36,37] in Ijesha land, Osun State, Nigeria, 21 plants for antityphoid treatment in Idoma land, Benue State, Nigeria, by [2]; 27 medicinal plants by Ampitan in Biu LGA, Borno State Nigeria and 22 plant species by [38] for diabetes treatment in South Western Region of Nigeria. This result may be because of the location of the LGA in the Sahel Savvanah of the country. [39] The importance of the identified plants to the local community cannot be over emphasized as they make use of them daily and preferred them to the orthodox medicines.39 The use of complimentary and alternative medicine (CAM) for treating typhoid fever is evident by the plants identified.

The use of herbal medicine for the treatment of typhoid fever is evident by the number of plant species identified. It is one way of balancing body systems and has become part of the cultural life and heritage of the people. [39,41] Many communities have therefore, since time immemorial, adopted different traditional methods, using plant and animal parts which are locally available to alleviate their health issues [39,40]. All the plants identified had at least one local name. The vernacular names used by the TMPs were uniform, probably suggesting that these plants are well known as remedies. [2,41,42]

The possible chemical compositions of the identified plants documented from literature may be responsible for the acclaimed antityphoid fever activities by the TMPs. The phytochemical constituents are secondary metabolites which might draw a link between the modern science and the traditional use of the plant.

Psidium guajava L. (Myrtaceae), Vitex doniana, Veronia amygdalina (Wild) Darke (Asteraceae) and Erythrina senegalensis DC. (Papilionoideae), water leaf extracts have been demonstrated by [43] to be effective against Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi . This is in conformity with the work of (44) who reported that these extracts if properly enhanced and harnessed could be very useful in healthcare delivery system for treatment of diseases. These plants contained phytochemicals like alkaloids, glycosides and anthraquinones. [43]

Observation was made by [45} in the survey of ethnobotany and conservation in Northern Nigeria that some plant species have multiple uses and treated and cured different ailments which included asthma, typhoid, stomach ache, headache, diarrheoa, whitlow, dysentery, anaemia, gonorrhoea, cough, among others. This also applies to the plants in Jere LGA in which part of the plants apart from being used to treat typhoid fever could also treat malaria,, cancer, high blood pressure, clustered headache and migraine. According to [46], since oral information can never be as accurate as was told to the recipient, a whole library of herbal information were being buried gradually with every person that dies. This resulted in slow pace of development of alternative medicine in Nigeria and in Africa in general.

TMPs used different additives and solvents in preparing their formulations. Some additives for example red potash (Jari kanwa) and potash (Kanwa) are mostly added to make some of the preparations that are taken orally more acceptable [29,33]. These can also be, milk, which can be added to decoctions and infusions to reduce the bitterness of the remedies in order to make them easier to drink. Lack of data on the biological roles of these materials like red potash and potash has been noted in the literature [29]. The plants mentioned in the preparations are evaluated generally by biological methods, but the materials added by the TMPs are generally not screened [29].

The potential of a plant to cure a disease can be estimated by its fidelity level (FL), [28,29] There was a high level of agreement among the TMPs in Gomari Airport Ward, Jere LGA on the plants used in treating typhoid fever. 6 of the plants had high citations and FL of 6 of the plants were high as well. This means that the medicinal properties of these plants can seriously be considered for more ethnopharmacological screening [41], since they are species widely applied by many people and for a long time have been so.

The pattern of traditional prescriptions revealed that majority of the medications involved a mixture of plants with only a few (1 preparation) treated with a high level of documentation. Traditional healers claimed that using multiple plants may provide a synergistic effect in therapeutic efficacy. [42,48]Although traditional medicines are still in common use by the TMPs in Borno State, Nigeria and other people in Nigeria, accurate information of the plant and their medicinal properties are held by only a few individuals in the community. These TMPs are almost without exception, community elders of 50 years of age or older, hence there is high probability that these invaluable knowledge and art of healing which have been religiously preserved for generations may not be passed on to the younger generation. To ensure that this information on plants is not lost with the current elderly generation of healers, documentation and preservation of this indigenous knowledge must be accorded utmost priority in this culture and other cultures, so that future generations can benefit from it in overcoming emerging problems of public health, agricultural and pharmaceutical sectors. [42]

The result of this study does not agree with that of Ampitan [39,46,49] where the age group of TMPs were (41-50) years respectively. In the area of study, age bracket ≤50 years were few (10.00 %) whilst age bracket & above 50 years were mainly the TMPs. Thus, the age of TMPs may be said to vary from place to place depending on where the survey is carried out. Many of the TMPs.

Majority of the TMPs in the LGA were men (90 %). This observation agrees with the one made by [39} who carried out a study of medicinal plants in Biu LGA, Borno State, where the traditional medicine practitioners were males.. The result however disagreed with that made by 50 in Abeokuta, Ogun State where women were the predominant traditional medicine practitioners. These results might be due to the people’s religion which forbid women from meeting or mingling with men either in the community or private. [39] However, of note, is that even in the South West of Nigeria, a study carried out in Abeokuta as well, by (38) on treatment of diabetes with plants had 96% male TMPs.

Majority of the TMPs agreed that knowledge of herbal treatment was mainly acquired by training (from their ancestors and parents) and is usually passed down from one generation to another. This ensures that the practice stays within the family. This is in agreement with the working of [38] who carried out a survey of the management of diabetes with plants in South Western regionof Nigeria that source of information on alternative medicine is mainly from the family (83%).

The plant part used was “traditionally” estimated, so the variations in the doses would either increase or decrease toxicity or affect the amount of the plant that would probably elicit pharmacological action. [51] Furthermore, lack of exact doses were reported by the TMPs in Jere LGA and the duration were not precisely given. This lack of exact doses in traditional practice has also been documented by many researchers [2,29,38,39,42,51,52]. The reason being that the healers failed to reveal all their knowledge.

Medicinal plants’ use is probably of a lower cost than allopathic pharmaceutical remedies [53] and most TMPs do not charge, they only received whatever the patients could offer except for the few who charged some money. In many of the plants studied pharmacologically, compounds were isolated from organic extracts of the plants while TMPs use water extract to cure their patients. The question how these nonvolatile substances could be the active constituent in phytomedicines normally administered as water extracts is interesting. One probable explanation might be that the minimum inhibitory concentration (μg range) of these compounds are low, as such they are effective.

Another reason is that in the plant material there could be co-extraction as plants often contain phytochemicals like saponins [51,5,4], that could lead to the solubility of and other non-soluble compound if it is in the same mixture. Plants are indispensable source of medicines for humans since creation [29,55] and constitute major economic resource of most countries on the planet including Nigeria. Most of the herbal medicines came from the trees followed by shrubs, many of which also have other uses such as providing timber and protection of the environment [29] They have taxonomic classes which enable their classification with respect to their role in economic development [29,56]

The unprecedented interest and demand for plants with medicinal properties and potency for treatment of various ailments is causing overexploitation of such plant genetic resources in the area of study. According to [29,57], the depletion rate of plants generally is high, yet little is known about a large portion of the world’s plant species especially tropical floras. When viewed against the present rate of extinction and decimation of the forests in this area, there is the need to conserve what is left as forest for posterity.

The most frequent liquid used in preparation is water, powders are sometimes suspended in milk to probably mask their bitter taste. [61]

The major method of administration is oral [29] followed by baths. Other ways of administration include direct application such as inhalation or bathing. Today, baths are still an important way to treat some illnesses and pains. [41,58,59]

The reported adverse effects effects when these antityphoid plants are used are dizziness and urine colouration according to the healers headaches, may be due to overdose of the medications or the additives. When the side effect is violent, stopping of the treatment is recommended [59,62]

The reported typhoid fever as diagnosed by the TMPs in fact may be symptoms only, which indicate that the traditional practice in Gomari Airport Ward of Jere LGA is symptom-directed as 100 % of the TMPs treated high fever and headache which are symptoms of diseases. This agreed with what was obtained in various regions of Mali [51], since there are a few other means of diagnosis apart from the symptoms observed by the patients [51,60]

CONCLUSION

The study provides information that could assist in the quest for locally sourced drug development in the treatment of typhoid fever in Nigeria. Screening and evaluation of the identified plants may be a next step in developing local therapeutic agents for typhoid fever.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Mallam Adamu Bello (for Hausa interpretation to English), Mallam Idi-Sarki Baka (a TMP who linked the authors with other TMPs), the Director of Pharmaceutical Services, Pharmacist Steven Jasini and Director of Medical Services, Dr Ibrahim Kida, Borno State Ministry of Health, Maiduguri. The West African Postgraduate College of Pharmacists, (WAPCP) with the Secretariat in Yaba, Lagos, is also appreciated for the opportunity to carry out this research work.

REFERENCES

- Nagsshelty K, Channappa ST, Gaddad SM (2010) Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella typhi in India. J. Infection Developing Countries 4(2): 70- 73.

- Aguoru CV, Ogaba JO (2010). Ethnobotanical survey of anti-typhoid plants amongst the Idoma people of Nigeria. Int. Sci. Res. J. 2:34-40.

- Iroha JR, Ilang DC, Ayogu TE, Oji AE, Ugbo EC (2010). Screening for anti-typhoid activity of some medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in Ebonyi state Nigeria. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol, 4(12): 860-864.

- Anita S, Indrayan AK, Guteria BS, Gupta CP (2002). Antimicrobial activity of dye of Casalpina sappan. J. Microbiol, 42: 359- 360.

- Doughari JH (2005) A comparative study on effects of crude extracts of some local medicinal plants and some selected antibiotics on Salmonella typhi. M. Sc. Federal University of Technology, Yola; Adamawa State, Nigeria. pp 1-4.

- Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED (2004). The global burden of typhoid fever. Bulletin World Health Org. 82: 346-353.

- WHO (2006a): World Health Organization Africa Traditional Medicine. Afrotech Representatives series, Brazzaville, pp 3:4.

- Doughari JH, Elmamoid AM, Nggara HP (2007a). Retrospective study on the antibiotic resistant pattern of Salmonella typhi from some clinical samples. Afr. J. Microbiol Res, 1: 33-36.

- James MR, Martin MO (2001). Multiple- drug resistant Salmonella typi Clin. Inf. Diseases. 17:135-136.

- Kethleen MP, Tenover FC, Reinser SB, Schmite FJ (2002). The prevalence of low level and high-level multiple resistance in Salmonella typhi from 19 European Hospitals. J. Antimcrob. Chemotherapy, 42: 489-495.

- Shrikala B (2004). Drug resistance in Salmonella typhi: tip of the iceberg. Online Health Alli Sci. 3(4):1-3.

- House D, Wain J, Ho AV, Diep TS, Chinh NT (2000). Serology of typhoid fever in area of epidemicity and its relevance to diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39(3): 1002- 1003.

- Smith A (2009). Bacterial resistance to antibiotics, In: Denyer SP, Hodges NA, Gorman SP (eds). Hugo and Russell’s Pharmaceutical Microbiology, 7th Edition, Blackwell Science Ltd, Blackwell Publishing Company, Oxford, pp 220-232.

- Raji MA, Mamman PH, Aluwong T (2011). Emerging strains and multidrugs resistant Salmonella species in humans and animals and the use of medicinal plants in Nigeria. Global Res. J. Microbiol, 1(1): 1-4.

- Tarr PE, Kuppens L, Jones TC, Ivanoff B, Aparin PG, Heyman DL (1999). Considerations regarding mass vaccination against typhoid fever as adjunct to sanitation and public health measures: potential use in an epidemic in Tajikistan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg, 61: 163-170.

- Threlfall EJ, Ward LR, Rowe B, Raghupathis, Chandrasekaran V, Vandepitte J, Lemmens P (1992) Widespread occurrence of multiple drug-resistant Salmonella typhi in India. European J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Diseases 11: pp990-993.

- Mourad AS, Metwally M, Nour El Deen A, Threffall EJ, Rowe B, Mapes T, Hedstrom M, Bourgeois AL, Murphy JR (1993). Multiple drug resistant Salmonella typhi. Clin. Inf. Diseases. 17 135-136.

- Keith PK, John RK (2005) Hidden epidemic of macrolide resistant pneumococci. Emerging Infect. Diseases, 11(6): 802 -807.

- Erdogrul OT (2002). Antibacterial activity of some plant extracts used in folk medicine. Pharm. Microbiol, 40: 269-273.

- BSG (2007): Borno State Government Official Diary of Ministry of Information, Home Affairs, Maiduguri, Nigeria. 5-7pp.

- MLS (2008): Ministry of Land and Survey, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. Office Memo File. Vol. 4. 55-58pp.

- BSBLS (2004): Borno State Bureau of Land and Survey. Map of Borno State, Nigeria. Maiduguri, Nigeria. p 1.

- NDHS (2008): Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, Abuja, Nigeria. National Population Commission and ICF Macro. https://pdf.usad.gov/pdfdocs/ PNADQ923.pdf. Access Date: 10/06/2010.

- Hess T, Stephen W, Thomas G (1996). Modelling NDVS from decadel rainfall data which the Northeast and arid zone of Nigeria. J. Env. Manag. 48: 349-261.

- NPC (2006): National Population Commission. Census Data, Borno State Nigeria, Federal Republic of Nigeria, Abuja.

- BOSADP (2008). Borno State Agricultural Development Programme. Office file

- Oral Communication (2013). Directors, Pharmaceutical Services & Medical Services and Deputy Director Pharmaceutical Services, Ministry of Health, Borno State on the establishment of Borno State Traditional Medicine Board, State Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Maiduguri. 13th-18th Nov. 2013.

- Ali-Shtayeh MS, Yaniv Z, Mahajna J (2000). Ethnobotanical survey in the Palestinia area: A classification of the heading potential of medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 73: 221-232.

- Togola A, Diallo D, Dembele S, Barsette H and Paulsen BS (2005). Ethnopharmacological survey of different uses of seven medicinal plants from Mali, (West Africa) in the regions Doila, Kolokari and Siby. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 1: 7-24; Suppl. i-xix.

- Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psycholog. Bulletin, 52: 281-302.

- Allen MJ, Yen WM (1979). Introduction to Measurement Theory. rooks/role Pub. Co. Belmont California. pp. 10-30.

- Gronlund NE, Linn RL (1990). Validity and reliability. In: Measurement and Evaluation in Teaching. 6th ed. Macmillan Pub. Co. New York, USA. pp47-105.

- Cronbach LJ (1984). How to judge tests. In: Essential of Psychological Testing. 4th ed. Harper & Row Pub. New York.

- NNMDA (2009): Nigeria Natural Medicine Development Agency. Federal Ministry of Science and Technology. Medicinal Plants of Nigeria. South West, Nigeria Vol. 1 Lisida Consulting Publishers, Lagos, Nigeria. 330pp.

- Aiyeloja AA, Bello OA (2006). Ethnobotanical potentials of common herbs in Nigeria: A case study of Enugu State. Edu. Res. Review, 1(1): 16-22.

- Kayode J (2008). Survey of plant barks used in nature pharmaceutical education in Yoruba land of Nigeria. Res. J. Botany, 3 (1): 17-22.

- Kayode J, Aleshinloye L, Ige OE (2008) Ethnomedical use of plant species in Ijesha land of Osun State, Nigeria. Ethnobiol. Leaflets¸ 12: 164-170.

- Abo KA, Adediwura AA, Jaiyesimi AE (2000). Ethnobotanical survey of plants used in the management of diabetes mellitus in South Western Region of Nigeria. J. Med. Medical Sci. 2(1): 20-24.

- Ampitan TA (2013). Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Biu local government area of Borno State, Nigeria. Comprehensive Herbs Medicinal Plants, 2(1): 7-11.

- Adesina SK (2008). Traditional medicine care in Nigeria. Today Newspaper, Wednesday, April 23.

- Macia MJ, Garcia E, Vidaurre PJ (2005). An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commercialized in the market of La Paz and E1, Alto, Bolivia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 97: 337-350.

- Ene A, Atawodi SE (2012). Ethnomedicinal survey of plants used by the Kanuri of North-Eastern Nigeria. Indian J. Tradit. Knowledge, 11(4): 640-645.

- Dawang ND, Datup A (2012). Screening of five medicinal plants for treatment of typhoid fever and gastroenteritis in Central Nigeria. Global Engineers Tech. Rev, 1(9): 1-5.

- Kilani AM (2006). Antibacterial assessment of whole stem bark of Vitex doniana against some enterobacteriaceae. Afr. J. Biotech, 5 (10): 958-959.

- Ugbogu OA, Akinnyemi OD (2004). Ethnobotany and conservation of Ribako Strict Natural Reserve in Northern Nigeria.Forestry Res. Mgt, 1(12): 83-93.

- Ogbole OO, Gbolade AA, Ajaiyeoba EO (2010). Ethnobotanical survey of plants used in the treatment of inflammatory diseases in Ogun State of Nigeria. European J. Sci. Res. 43(2): 183-191.

- Abebe W (1984). Traditional pharmaceutical practice in Gonder region, North Western Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol, 11: 33-47.

- Teferi H, Gedifi A, Heinz – Jurgen H (2002). Herbalists in Addis Ababa and Butajira, Central Ethiopia: Mode of service delivery and traditional pharmaceutical practice. Ethiopian J. Health Dev. 1(2): 191- 197.

- Ajaiyeoba EO, Oladapo O, Fawrole OI, Bolaji OM, Akinloye DO, Ogundahunsi OAT, Falade CO, Gbotoso GO, Itiola OA, Happi TC, Ebong OO, Ononiwu IM, Osowole OS, Oduola OO, Ashidi JS, Oduola AMJ (2003). Cultural categorization of febrile illness in correlation with herbal remedies used for treatment in south western Nigeria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 85: 179-185.

- Idu M, Erhabo E, Efijueme HM (2010). Documentation of medicinal plants sold in market in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Tropical J. Pharm. Res. 9(2): 110-118.

- Togola A, Austarheim I, Theis A, Diallo D and Paulsen BS (2008). Ethnopharmacological uses of Erythnia senegalensis: A comparison of three areas in Mali and a link between traditional knowledge and modern biological science. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 4:6-16. supp. i-xiv.

- Longuefosse JL (1996). Medical ethnobotany survey in Martinique. J. Ethopharmacol. 53: 117-142.

- Naranjo P (1995). The urgent need for the study of medicinal plants. In: Schultes RE, Von Reis, S. (eds). Ethnobotany: Evidence of Discipline. Chapman & Hall, Hong Kong. pp362-368.

- Patrick – Iwuanyanmu KC, Sodipo OA (2007). Studies on saponins of leaf of Clerodendrenn thomsonae Balfour. Acta Biologica szegediensis. 5(12):117-123.

- Dery BB, Otsyina R (2000). The 10 priority medicinal trees of Shinyanga, Tanzania. Agroforestry Today 12(1): 9-12.

- Ekanem AP, Udoh FV (2009). The diversity of medicinal plants in Nigeria: An overview. Symposium Series, Vol. 1021: pp. 135, 147.

- Igoli JO, Ogaji OG, Tor-Ayim TA, Igoli NP (2005). Traditional practice amongst the Igede people of Nigeria. Part II. Afr. J. Trad. CAM, 2(2): 134-153.

- Bourdy G, De Walt SJ, Chiwez de Michei LT, Roca A, Debaro E, Munoz V, Balderrama L, Quenevo C, Gimenez A (2000). Medicinal plant use of the Tacana, an Amazonian Bolivian ethnic group. J. Ethnopharmacol, 70:87-109.

- Fernandez EC, Sandi YE, Kokosak L. (2003). Ethnobontanical inventory of medicinal plants used in the Bustillo Province of the Potosi department, Bolivia. Fitoterapia, 74:407-416.

- Bah S, Diallo D, Dembélé, Paulsen BS (2006). Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of Shistosomiasis in Niono District, Mali. J. Ethnopharmacol, 105:387-399.

- Ganesan G Ram, S. Sundar, P. Kunal, J.K. Giriraj, P.V. Vijayaraghavan (2015) Methylprednisolone Acetate Versus Triamcinolone Acetonide for Pain Relief in Spinal Nerve Root Block for Low Back Pain

- Goyal S, Verma S, Gupta, M.C. (2015) Modulatory Role of Morphine and Gabapentin as Anti-inflammatory Agents Alone and on Co-administration with Diclofenac in Rat Paw Edema.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences