Prevalence and Associated Factors of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting among Pediatric Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery under General Anesthesia at Addis Ababa Public Hospital in 2021/22: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study

Desta Waktasu*, Lidya Haddis, Emebat Seyoum, Mistre Nigussie and Molla Amsalu

Department of Pharmacy Practice, University Adigrat, Adigrat, Ethiopia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Desta Waktasu Department of Pharmacy Practice, University Adigrat, Adigrat, Ethiopia E-mail:olidesta894@gmail.com

Received date: September 05, 2024, Manuscript No. IPIJCR-24-19596; Editor assigned date: September 04, 2024, PreQC No. IPIJCR-24-19596 (PQ); Reviewed date: September 23, 2024, QC No. IPIJCR-24-19596; Revised date: April 04, 2025, Manuscript No. IPIJCR-24-19596 (R); Published date: April 11, 2025, DOI: 10.36648/IPIJCR.9.2.011

Citation: Waktasu D, Haddis L, Seyoum E, Nigussie M, Amsalu M (2025) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting among Pediatric Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery under General Anesthesia at Addis Ababa Public Hospital in 2021/22: A Multi-Center Cross- Sectional Study. Int J Case Rep Vol:9 No:2

Abstract

Background: Post-operative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) is a common and distressing complication following surgical procedures, affecting up to 70% of paediatric patients. PONV can lead to delayed recovery, increased hospital stay, and reduced patient satisfaction, posing a significant burden on healthcare systems. In the paediatric population, PONV is particularly concerning due to the potential risk of aspiration, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances.

Methods: A multicenter cross-sectional study method was carried out, with study population of 186 surgical pediatrics patient populations from December 1, 2021 to May 30, 2022. The magnitude of pediatrics population was evaluated according to specific criteria encompassing sociodemographic and preoperative pediatrics characteristics, intraoperative, and postoperative characteristics of paediatrics PONV.

Results: The magnitude of pediatrics PONV in PACU and Ward identified with their associated risk factors of perioperative anxiety, motion sickness and long duration of surgery and anesthesia.

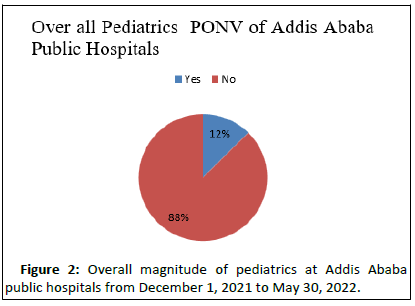

Conclusion: The magnitude of paediatrics PONV at Addis Ababa Public Hospital is 12%. Using opioid for postoperative management is not related to paediatrics PONV in our study. Reduction strategy as well as prevention and treatment are vital for enhancing paediatrics patient safety and perioperative care quality.

Keywords

Vomiting; Surgery; PONV; Comorbidity; Paediatrics patient

Introduction

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) is not a recent problem; in the early 1990’s, it was seen as a minor one, but it has recently grown to be a serious issue. PONV, which can persist for up to 24 hours following surgery, is a condition that causes nausea, vomiting, or retching in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU). The terrible feeling of nausea that comes along with the consciousness of wanting to vomit is called nausea.

Vomiting is the violent, involuntary evacuation of stomach contents through the mouth. This study focused on Postoperative Vomiting (PONV) in children between the ages of 4 and 17 because it is difficult to report nausea in young children.

The vomiting area, situated in the dorsal part of the lateral reticular formation, is where vomiting occurs. Acetylcholine (ACH) and Histamine (H1) receptors are the most prevalent in the vomiting center. The Nucleus Tractussolitarius (NTS), the Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone (CTZ), and the cerebral cortex all provide information. The cerebral cortex receives afferent CNS input from circuits that mediate pain, smell, sight, emotion (fear/anxiety), and biological abnormalities. Children are affected by PONV twice as frequently as adults, and it can result in complications such extended PACU stays, aspiration, wound bleeding, and unanticipated readmissions, all of which place a significant financial burden on the patients. Children are twice as prone as adults to outsource PONV.

PONV is a frighteningly common complication among children, with estimates ranging from 33.2 percent to 82 percent depending on the patient's risk factors. PONV is a dangerous complication that has been linked to an increased mortality risk in both adults and children. PONV's negative effects range from patient distress to surgical morbidity. While it is difficult to eliminate PONV in many cases completely, the risk can be reduced by using multimodal non-opioid analgesic regimens, whole intravenous medicines rather than volatile anesthetics, and a proper prophylactic medication regimen. Identifying the prevalence and prevention of Pediatric Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) is thought to improve patient satisfaction and provide cost-effective care while caring for patients.

Many studies indicate that the higher prevalence of pediatric postoperative nausea and vomiting is due to associated patient factors, anesthesia factors, and surgical factors. PONV has detrimental effects on the patient, surgical recovery, the healthcare professional, and the institution. Children should be stratified to receive appropriate management of risk factors and antiemetic therapy. Wherever possible, strategies to decrease exposure to emetogenic substances should be used. By decreasing baseline risk factors and correctly treating those at risk, we can provide better perioperative care to children.

This study aimed to know the magnitude and associated factors of PONV among pediatrics. We also compared the magnitude in OR, PACU, and Ward. We hypothesized that postoperative pain management in pediatrics with opioids is not a major concern like other factors.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A multicentre cross-sectional study of 186 patients was examined for PONV at three selected Addis Ababa Public Hospitals, Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Paulus Specialized Hospital and Menilik II Specialized Hospital [1].

Sample size determination

The sample size is calculated by using single population proportion formula. Previously, the prevalence of pediatric PONV for pediatrics age of 6–11 in Baghdad is 30%. using a single population proportion formula with 95% confidence interval or 5% level of significance and 5% margin of error, the sample size calculated as follow as:

N=((Zα/2)2 × P(1-P))/d2

Where;

n is minimum sample size required

Zα/2 is the standard normal variable at (1-α)% confidence level and α (level of significance), Usually 95% confidence level is used = 1.96;

P is taken to be 0.3.

q =1-p = 0.7

d=is the margin of sampling error tolerated, assumed to be 0.05.

n=(1.962 ×0.3×0.7)/(0.05)2 ≈ 32

By using correction formula for finite population since source population is below 10,000, nf=n/(1+n/N),where is n is the minimum sample size and N is the total number of pediatric patients operated per three month at three hospitals is 450 from situational analysis, and using adjusted sample size formula for small population, 323/(1+(323/450)) ≈ 188. Therefore, the estimate sample size of the study will be 188. By taking 10% non-response rate the total sample will be ≈ 207. From the three hospitals of 450 total number of patient per three month, TASH, NTASH=220, MIIRH, NMIIRH=80 and SPMHC, NSPMHC=150, the Total N=450, so sample size for each hospital will calculated as follow using this formula:

nj = n/N × NJ

nTASH=92, nMIIRH=33, nSPMHC=63,

Where

j=1, 2, 3……k

n=total sample size for the three hospitals

k=is the number of strata.

nj=is the sample size of each hospital allocation

Nj=is the source population size of each hospital

nTASH=is sample size for Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital

nMIIRH=is sample size for Menilik II Referral Hospital.

nSPMHC=is sample size for St. Paulos Hospital Medical College

Sampling technique

Simple random sampling technique was used after labelling the record chart during the study period.

Data type and method of data collection

Primary as well as secondary data information was used to conduct this study. The primary data included respondent’s socio economic, demographic, intra as well as immediate postoperative conditions. For collection of primary data, a paediatric parents/guards were interviewed. For the purpose of quality primary data collection, appropriate orientation and pre-test was given for data collectors (three graduate degree anaesthesiology professionals). In addition, timely supervision was conducted by the principal investigator.

Inclusion criteria

All pediatric patients of 4–17 years old enrolled to undergo elective surgery under GA with endotracheal intubation and have consent from their family/guardian to participate in the study were included.

Exclusion criteria

Pediatric patients admitted to ICU.

Data processing and analysis

For generation of valuable result from this study, descriptive statistics as well as econometric model was applied. Data was checked manually for completeness and clarity. After this, it was coded, entered, cleaned and analyzed using SPSS version 24 software program. Descriptive statistics was used to explore the socio-demographic characteristics of patients, and the results were summarized as frequencies and percentage. Bivariate and multivariate analysis was used to see the effect of independent variable on outcome variable. Variables, which were significant on bivariate analysis is at p-value less than or equals to 0.25 was taken to multivariate analysis. The strength of association was measured by 95% confidence interval and P-value of 0.05 was used as statistically significant in all cases [2].

Results

The magnitude of PONV among pediatrics population was 12%, while the associated factors are anxiety, duration [3].

Socio demographic Characteristics of Addis Ababa public hospital pediatric patients (Tables 1-3).

| Variables | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Sex | Male | 105 | 56.5 |

| Female | 81 | 43.5 | |

| Age (years) | 4–10 | 132 | 71 |

| 11–17 | 54 | 29 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18 | 40 | 21.5 |

| 18–25 | 129 | 69.4 | |

| <26 | 17 | 9.1 | |

| Preoperative anxiety | Yes | 81 | 43.5 |

| No | 105 | 56.5 | |

| ASA physical status | I | 102 | 54.8 |

| II | 73 | 39.2 | |

| III | 8 | 4.3 | |

| IV and above | 3 | 1.6 | |

| Comorbidity | No comorbidity | 65 | 35 |

| Has comorbidity | 121 | 65 | |

| Type of comorbidity | Non-critical | 40 | 21.5 |

| Critical | 146 | 78.5 | |

| History of surgery | Yes | 20 | 11 |

| No | 166 | 89 | |

| History of PONV | Yes | 44 | 23.7 |

| No | 142 | 76.6 | |

| History motion sickness | Yes | 159 | 85.5 |

| No | 27 | 14.5 | |

| Family history of smoking | Yes | 48 | 25.8 |

| No | 138 | 74.2 |

Table 1: Intraoperative characteristics of pediatrics PONV at Addis Ababa public hospitals.

| Variables | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

| Induction used | IV induction | 159 | 87.5 |

| IH induction | 27 | 12.5 | |

| Maintenance used | IV induction | 164 | 90.2 |

| IH induction | 22 | 9.2 | |

| Types of surgery | Ophthalmic | 169 | 92.7 |

| Non-ophthalmic | 17 | 7.3 | |

| Total blood loss | Below allowable | 14 | 7.3 |

| Normal | 167 | 90 | |

| Above allowable | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Total Fluid Given | Below allowable | 30 | 16.2 |

| Normal | 156 | 79.4 | |

| Above allowable | 10 | 5.4 | |

| Intra-operative analgesic | Opoid | 166 | 90.2 |

| Non-opoid | 10 | 9.8 | |

| Duration of surgery | <35 minute | 13 | 7 |

| >35 minute | 173 | 93 | |

| Duration of anesthesia | <45 minute | 14 | 7.5 |

| >45 minute | 172 | 92.5 |

Table 2: Intraoperative pediatrics PONV characteristics at Addis Ababa public hospitals from December 1, 2021 to May 30, 2022 (n=186).

| Variables | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| PON in PACU | Yes | 38 | 8.1 |

| No | 148 | 91.9 | |

| POV in PACU | Yes | 26 | 14 |

| No | 160 | 86 | |

| PONV IN PACU | Yes | 24 | 12.9 |

| No | 162 | 87.1 | |

| PON in PACU | Yes | 23 | 12.4 |

| No | 163 | 87.6 | |

| POV in PACU | Yes | 15 | 8.1 |

| No | 171 | 91.9 | |

| PONV in PACU | Yes | 13 | 7 |

| No | 173 | 93 | |

| Postoperative pain | Mild | 115 | 61.8 |

| Moderate | 52 | 28 | |

| Severe | 19 | 10.2 | |

| Analgesia given in PACU | Opoids | 46 | 25 |

| Non opoids | 142 | 75 | |

| Analgesia given in Ward | Opoids | 24 | 12.6 |

| Non opoids | 164 | 87.4 | |

| Time PONV occurs | 0–6 hours | 53 | 28.5 |

| 6–12 hours | 20 | 10.8 |

Table 3: Post-operative.

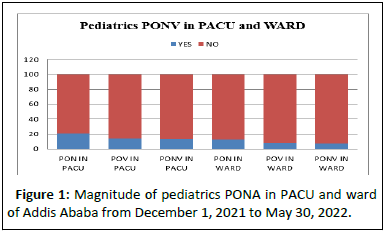

Bar graph shows summary of a higher incidence of postoperative nausea in the PACU setting, but a lower incidence of both nausea and vomiting in the WARD of Addis Ababa public hospitals setting for paediatric patients Figure 1.

Figure 1: Magnitude of pediatrics PONA in PACU and ward of Addis Ababa from December 1, 2021 to May 30, 2022.

The pie chart shows that in the overall summary, the majority (88%) of pediatric patients in Addis Ababa public hospitals do not experience postoperative nausea and vomiting, while a smaller percentage (12%) do experience PONV Figure 2.

Figure 2: Overall magnitude of pediatrics at Addis Ababa public hospitals from December 1, 2021 to May 30, 2022. Binary logistic regression showing the significance of associated factors with a significance value of <0.02 (Table 4).

| Variables | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I for EXP(B) | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.637 | 0.789 | 0.294 | 2.117 |

| Sex | 0.51 | 0.748 | 0.315 | 1.777 |

| BMI | 0.755 | 0.88 | 0.395 | 1.963 |

| Anxiety | 0.025 | 1.333 | 0.552 | 3.223 |

| ASA class | 0.457 | 1.374 | 0.595 | 3.174 |

| Preoperative fasting | 0.33 | 1.54 | 0.646 | 3.671 |

| Comorbidity | 0.512 | 1.084 | 0.852 | 1.38 |

| History of surgry | 0.608 | 1.347 | 0.431 | 4.206 |

| History of PONV | 0.018 | 0.526 | 0.126 | 2.205 |

| Motion sickness | 0.022 | 0.914 | 0.185 | 4.507 |

| Opoid pre-medication | 0.039 | 3.851 | 1.072 | 13.831 |

| Pre-medication used | 0.391 | 0.539 | 0.131 | 2.21 |

| Smoking | 0.016 | 0.145 | 0.03 | 0.701 |

| Pre-medication used | 0.208 | 1.424 | 0.821 | 2.47 |

| Types of induction | 0.253 | 2.607 | 0.504 | 13.476 |

| IV used | 0.847 | 1.049 | 0.646 | 1.702 |

| IH maintenance | 0 | 0.148 | 0.234 | 0.91 |

| Caudal anesthesia | 0.17 | 0.507 | 0.192 | 1.338 |

| Types of surgery | 0.0125 | 0.789 | 0.574 | 1.086 |

| Total blood loss | 0.416 | 1.407 | 0.618 | 3.202 |

| Fluid given | 0.078 | 0.466 | 0.199 | 1.089 |

| Intraoperative analgesia | 0.322 | 1.683 | 0.601 | 4.712 |

| Duration of surgery | 0.012 | 0 | 0 | |

| Duration of anesthesia | 0.015 | 15.846 | 0 | |

| Post-operative fluid | 0.921 | 0.486 | 0 | 755945.5 |

| Pain | 0.114 | 0 | 0 | 7.681 |

| PACU analgesia | 0.886 | 1.295 | 0.038 | 44.315 |

| Ward Analgesia | 0.223 | 313.446 | 0.03 | 3.117 |

Table 4: Binary logistic regression of pediatrics PONV at Addis Ababa public hospitals from Decemeber 1, 2021 to May 30, 2022 (n=186).

A significance value of <0.02 from binary logistic regression re-entered to multiple logistic regression and re-analysed as below, then a significant value of <0.05 from multiple logistic regression are assumed to be associated risk factors of PONV Table 5.

| Variables | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I for EXP(B) | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Anxiety | 0 | 0.771 | 0.551 | 1.81 |

| Previous motion sickness | 0.021 | 0.381 | 0 | . |

| History of PONV | 0.015 | 0.627 | 0.019 | 21.215 |

| Inhalational anesthesia | 0.91 | . | . | . |

| Surgery duration >30 min | 0.019 | 0.42 | 0.601 | 1.302 |

| Anesthesia duration >45 min | 0.001 | 0.12 | 1.02 | 3.7 |

| Opoid analgesia | 0.223 | 0.446 | 0.03 | 32.117 |

Table 5: Multiple logistic regression of pediatrics PONV at Addis Ababa hospitals from December 1,2021 to May 30, 2022 (n=186).

Discussion

The main results of the present study were as follows:

• The overall paediatrics PONV level did not differ from the existing data except the case of using opioid for pain management in our case.

• There was a significance in anxiety in paediatrics in to resulting PONV.

• There was a PONV from previous motion sickness.

• There was PONV if there is previous history of PONV.

• Increment of duration of surgery and anaesthesia both results in PONV [4].

In contrast to study done in different areas of the world, our research states opioid postoperative analgesia does not result in PONV providing the odds ratio for opioid analgesia is 0.446, indicating that the use of opioid analgesia is associated with 55.4% lower odds of the outcome, compared to not using opioid analgesia, holding all other variables constant. However, the confidence interval is extremely wide, ranging from 0.030 to over 3 million, suggesting that the estimate is highly imprecise and the effect is not statistically significant. Maintaining a vigilant approach to identifying and addressing PONV risk factors can ensure that the majority of paediatric patients continue to have a smooth and comfortable recovery.

Sex is not a significant predictor of the outcome, as the pvalue of 0.510 is greater than 0.05 in our study. The odds ratio of 0.748 indicates that the odds of the outcome are 25.2% lower for males compared to females, but this effect is not statistically significant [5].

BMI is not a significant predictor of the outcome, as the pvalue of 0.755 is greater than 0.05. The odds ratio of 0.880 suggests that for every one-unit increase in BMI, the odds of the outcome decrease by 12%, but this effect is not statistically significant.

These researches suggest that the medical teams in Addis Ababa public hospitals are effective at managing postoperative vomiting, but may need to focus more on addressing nausea, particularly in the PACU setting [6]. Investigating factors contributing to nausea, such as anaesthetic management, pain control, or patient-specific risk factors, could help inform targeted interventions to further improve PONV outcomes.

The presence of comorbidities is not a significant predictor of the outcome, as the p-value of 0.512 is greater than 0.05. History of motion sickness have been suggested to be associated with paediatrics PONV, as the p-value of 0.022 is less than 0.05. The odds ratio of 0.914 suggests that the odds of the outcome are 8.6% lower for individuals with a history of motion sickness, and this effect is statistically significant.

In recent public health research, the anxiety reduction method with family of children has been used as an important term separate from motion sickness. Both have been considered independent risk factors for several risk factors, such as long duration of surgery and anaesthesia. Finally, the use of inhalational induction does not associate with paediatrics PONV in our setting contradicting research done by Kenny GNC [7-9].

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of postoperative nausea and vomiting was 12%. It was moderate compared with most studies conducted in Africa and other parts of the world. History of motion sickness/PONV/anxiety and duration of surgery and anesthesia above 45/30 minute respectively were the major factors associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting/ PONV/in pediatrics. We recommend that since medicine is ever dynamic science further research is necessary on magnitude and associated factors of pediatrics postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Limitations

The limitations of this study were, we face financial problem since it is multicenter.

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to praise Lord for everything and then my deep gratitude and appreciation goes to my advisor Lidya Haddis for her continuous encouragement, suggestions and valuable advice to develop this thesis.

Secondly. I would like to thanks Addis Ababa University for being sponsorship and approval of my research to conduct this study

Thirdly, I would like to thank Debre Berhan University for giving me chance to learn Master of Science in anesthesia.

Finally, my special thanks go to the writer of the literatures I used for citations.

Author Contrubutions

Advisor: Lidya Haddis

Principal Invigilator: Desta Waktasu (MSc Student) The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Desta Waktasu and Lidya Haddis

Data collection: Desta Waktasu

Analysis and interpretation of results: Desta Waktasu, Lidya Haddis, Emebat Seyoum and Mistre Nigussie

Draft manuscript preparation: Desta Waktasu and Molla Amsalu.

All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the AAU and conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (approval number approval number (Ames /17/2021/2022). This study was guided by ethical standards and national and international laws. All pediatrics Guards/family signed the consent form after receiving instructions regarding the possible risks and benefits and was granted privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity rights. The participant’s guards were free to stop participating any stage of the experiment without giving reasons for their decision.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the study results can be provided followed by request sent to the corresponding author’s e-mail.

Conflicts Interest

None.

References

- Kocaturk O, Keles S, Omurlu IK (2018) Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting in pediatric patients undergoing ambulatory dental treatment. Niger J Clin Pract 21:597–602

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hung L, Chou M, Liang C, Liu K (2012) Being older as a risk factor for vomiting in those undergoing spinal anesthesia. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 3:68–72

- Moon YE (2014) Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Korean J Anesthesiol 67:164–170

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martin S, Baines D, Holtby H, Carr AS (2016) Guidelines on the Prevention of Post-operative Vomiting in Children. Assoc Paediatr Anaesth G B Irel (Spring) 1–36

- Pierre S, Whelan R (2013) Nausea and vomiting after surgery. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 13:28–32

- McCracken G, Houston P, Lefebvre G (2008) Guideline for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 30:600–607

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Urits I, Orhurhu V, Jones MR, Adamian L, Borchart M, et al. (2020) Postoperative nausea and vomiting in paediatric anaesthesia. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim 48:88–95

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nurhussen A, Al’ferid F, Birhanu T (2020) Prevalence and associated factors of post-operative nausea and vomiting in elective surgical patients operated under anesthesia at Tikur Anbesa Specialized Teaching Hospital. Anesthesiology 91:1693–1700

- Rose JB, Watcha MF (1999) Postoperative nausea and vomiting in paediatric patients. Br J Anaesth 83:104–117

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences