Parents Attitude and Practice Towards the Girl Child Education in Esan West Local Government Area of Edo State Nigeria

Akpede N1,*, Eguvbe AO2, Akpamu U3, Asogun AD1, Momodu MO4 and Igbenu NE4

1Department of Community Medicine, Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Irrua, Irrua, Edo State, Nigeria

2Department of Community Medicine, Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

3Faculty of Public Health, Department of Health Promotion and Education, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

4Faculty of Clinical Sciences, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Nosa Akpede

Department of Community Medicine

Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital

Irrua, Irrua, Edo State, Nigeria

Tel: +2348166339853

E-mail: nosaakpede@yahoo.com

Received Date: May 22, 2018 Accepted Date: May 29, 2018 Published Date: June 05, 2018

Citation: Akpede N, Eguvbe AO, Akpamu U, Asogun AD, Momodu MO, et al. (2018) Parents Attitude and Practice towards the Girl Child Education in Esan West Local Government Area of Edo State in Nigeria. J Women’s Health Reprod Med. Vol.2 No.1:3

Abstract

The girl child education is a major issue in developing countries. Female education is influenced by culture, religion and other practices especially in rural areas. No study has previously investigated the situation in a sub-urban community in Edo State, Nigeria. This study was conducted to assess parental attitude, practice and factors influencing girl child education amongst parents' in the area. The study was a descriptive cross-sectional study targeted at parents with at least a child of school age using an interview based semi-structured questionnaire. Data was collected using the multistage sampling technique and was analyzed via SPSS version 21.146 parents participated in the study with 58.90% and 69.20% showing good attitude and practice toward girl child education respectively. This degree of attitude was negatively influenced by factors such as lack of finance and large family size. One such factor that affected the level of education the girl child recieved was behavioral attributes (54.8%). However, practice towards education of the girl child was found to be good. Girl child education remains a veritable tool in a nation’s development.

Keywords

Parental; Attitude; Practice; Girl child; Education

Introduction

Education is the light that shows the way, medicine that cures and the key which opens all doors. Its relationship with development has been well established. In fact, schooling/education improves health, productivity, bringing about empowerment and reduces negative features of life such as child labour [1]. There have been important linkages between education and socioeconomic development of any society and the international community and governments all over the world have recognized and made commitments for citizens to have access to education. Because of the importance of education, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights stated that every person has a right to education [2]. In 1990, the World Conference on ”Education for All” which took place in Jomtien, Thailand, declared among others that every person shall be able to benefit from educational opportunities designed to meet their basic learning needs [2]. In realization of the importance of the female child, concerted efforts were mounted by the governments at various levels to improve female participation in education and redress the gender inequalities in education enrolment and retention. UNICEF’s long-term goal is for all children to have access to complete and quality education. The international goals connected to girls’ education include Millennium Development Goals, a World Fit for Children Goals and Dakar Goals [2,3].

Despite these effects by agencies and governments since 1948, there are still inequalities in educational access, achievements and high levels of absolute educational deprivation especially in children [4] and till date girls constitute the largest population of illiterate children [3] across the globe. The situation is more serious in most African countries because it is believed that women are in the home for domestic chores, home careers and when married, tend to forget their parents and focus on their new home [5,6]. Many low and middle income countries are faced with concerns which usually give little room for designing and initiating programs to improve female education despite the fact that measures could be adopted within tight financial limits to redress gender inequality in educational enrolment and retention [7].

The benefits of educating the girl child cannot be over-emphased as educating the girl child produces mothers who are educated and who will in turn educate, care and provide for their families and children. Educating the girl child translates to better health for the future generation, reduces child morbidity and mortality and triggers a snowball effect of achieving all other Sustainable Development Goals in a viable manner [5]. In fact, researches showed that every extra year of school for girls increases their life time income by 15%, and improves the standard of living for their own children as women invest more of their income in their families than men do [8].

Most children have two main educators in their lives -their parents and their school teachers. Parents are the prime educators until the child attends an early years setting or starts school and they remain a major influence on their children’s learning throughout school and beyond. There is no universal agreement on what parental involvement should be but parents’ positive attitude towards the education of girl child education is important in determining attendance and academic achievement of the child. Turn bull identified four basic parental roles – parents as educational decision makers; parents as parents; parents as teachers and parents as advocates [9]. Hence we can see that family involvement is the strongest predictor of child educational outcome. No study of such has been carried out in Esan West Local Government Area of Edo State and this is of great concern. This study therefore determines the attitude and practice of parents towards girl child education in Esan West Local Government Area and assesses the factors that may influence their attitude and practice.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in Esan West Local Government Area of Edo State with Ekpoma as the administrative headquarter. The area is located on Latitude 60 44’ 34.80” N and Longitude 6008’ 25.04"E [10] and occupies a land mass of 502 km2 with a population of 125,842 of which 63,785 are males and 62,057 are females and a density of 250.7 inhabitants per km2 according to 2006 census figures. A population projection of 193,392,500 is estimated as at 2016.

The Local Government Area is politically divided into 10 political wards which are; Ogwa, Ujiogba, Egoro Amede/Idoa/Ukhun/ Egoro Naoka, Eguare/Emaudo, Ihumudumu/Ujemen/ Idumebo/ Uke, Iruekpen, Ukpenu/Emuhi/Ujoelen, Urohi/Akugbe, Uhiele, Illeh. The major occupation of the people is farming and others include teaching and trading. The people are Esan speaking, traditional and Christian religion is predominant with only a few Muslims. There are several infrastructures such as markets, schools, hospitals, banks, post office, churches, and mosques in the area and houses two universities which are Ambrose Alli University (AAU), Ekpoma and Samuel Adegboyega University (SAU), Ogwa. Basic amenities such as piped water, electricity and good roads range from adequate to inadequate. The major means of transportation is by roads using motorcycles, cars, and bicycles. The study area consists of 17 government secondary schools and 21 government primary schools with several private primary and secondary schools.

The study population comprised of parents with at least a girl child of school age in Esan west local government area of Edo state. School age group used in this research refer to children between the ages of 5 – 25 years and that have inhabited the study area for a period not less than a year. The study was a descriptive cross sectional done over a period of 8 months.

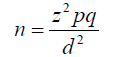

Sample size was determined using the Cochran formula for cross-sectional study;

where: n=Minimum sample size, z=Standard normal deviate at 1.96 corresponding to 95% confidence interval, p=prevalence of girl child education in Edo state; which is 9.55% or 0.0955 according to UNESCO report in Oyitso and Olomukoro 11, q=1- p=1-0.0955=0.9045 and d=degree of precision at the confidence of 5%=0.05. This gave a minimum sample size of 132 and 10% non-response was added to give a total of 146.

A multistage sampling technique consisting of three stages was used in this study. In the first stage, the local government area was taken as a cluster and stratified into wards. In the second stage, a simple random sampling method was used in selecting one from the ten wards. In the third stage, homes/compounds in the selected ward (covering Eguare/Emaudo) were visited to administering questionnaires to consenting parents with female children of school age who met the criteria for inclusion till the sample size was completed. The disadvantage of this sampling method is the fact that some individuals such as farmer, civil servants and market women may be left out or misrepresented. To correct this, we took note of homes with such individuals and visit them during weekends.

A semi-structured questionnaire was developed and used for data collection, with questions based on the study objectives. Validity of the instrument for data collection was ensured through the development of a draft instrument by consulting relevant literatures and subjecting the draft to independent, peer and expert reviews. Reliability was determined by first subjecting 10% of the questionnaires to pre-test in a neighboring town at Irrua; Esan Central local government area. Reliability testing was then determined using the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient and a coefficient of 0.881 was obtained and considered reliable since it was greater than 0.5. The questionnaire had sections on the socio-demographic characteristics, attitude, practice and factors affecting girl child education.

The data collected was entered into a spread sheet and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0. The data was subjected to descriptive statistic (frequency, percentage and mean) and inferential statistics (Chi-Square test). Where applicable, statistical difference was determined at a confidence interval of 95% and p<0.05 was considered significant. Results were presented in suitable tables and charts. Attitude of parents towards girl child education was measured on a 5 point liker scale with 10 questions in section B of the questionnaire. Total obtainable score was 50 while a score of 0 -25 was graded as poor attitude, 25-35 as fair attitude and >35 good attitude. Practice of girl child education was measured with 7 questions in section C of the questionnaire with a total obtainable score of 14, in which 0-7 was graded as poor practice, [7-11] was graded as fair practice while >10 was graded as good practice. Chi square test was used to test the association between socio-demographic variables with attitude and practice of girl child education. Significance level was set at p<0.05.

The principle of the declaration on the right of the subject was employed after approval by the local government council. Verbal consent was gotten from participants who were assured of strict confidentiality as regards their responses. Proper community entry was done. Before participants were enrolment in the study, informed consent was sought for and obtained.

Results

Table 1 above shows the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. Respondents in the age group 35 -44 years were the most represented (40.4%) and followed by those in the age group of 45-54 years (33.6%) with those aged 55-64 years with the smallest proportion (11.4%). There were more male (55.5%), Christians (79.5%) and the Esan ethnic group (62.3%) compared to others. They were mostly married (75.3%) with majority of them been professionals (32.1%) closely followed by business individuals (25.9%). Other occupations which included drivers, motorcyclists, and hair stylists accounted for 11.7% while artisans make up 17.9%, farmers and students 6.2% each. 31.5% of them attained tertiary level of education while 29.5%, 28.8% and 10.3% attained primary, secondary and no form of education respectively. Parents who had two girls of school age made up the majority (37.0%). *Indicates not applicable.

| Demographic Characteristics | Variables | Frequency (n= 146) | Percent (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (in years) | 25–34 | 21 | 14.6 | - |

| 35–44 | 59 | 40.4 | 37.4 ± 8.8 | |

| 45–54 | 49 | 33.6 | - | |

| 55–64 | 17 | 11.4 | - | |

| Sex | Male | 65 | 44.5 | - |

| Female | 81 | 55.5 | * | |

| Ethnicity | Bini | 12 | 8.2 | - |

| Esan | 91 | 62.3 | * | |

| Etsako | 13 | 8.9 | - | |

| Hausa | 3 | 2.1 | - | |

| Ibo | 5 | 3.4 | - | |

| Ika | 2 | 1.4 | - | |

| Owan | 16 | 11.0 | - | |

| Urhobo | 2 | 1.4 | - | |

| Yoruba | 2 | 1.4 | - | |

| Religion | Christian | 116 | 79.5 | |

| Muslim | 26 | 17.8 | * | |

| ATR | 1 | 0.7 | - | |

| Others | 3 | 2.1 | - | |

| Marital status | Married | 110 | 75.3 | - |

| * | ||||

| Single | 7 | 4.8 | ||

| Divorced | 8 | 5.5 | - | |

| - | ||||

| Separated | 21 | 14.4 | ||

| Occupation | Artisans | 26 | 17.9 | |

| Farmer | 9 | 6.2 | * | |

| Business | 38 | 25.9 | - | |

| Students | 9 | 6.2 | - | |

| Professional | 47 | 32.1 | - | |

| Others | 17 | 11.7 | ||

| Level of education | None | 15 | 10.3 | - |

| * | ||||

| Primary | 43 | 29.5 | ||

| - | ||||

| Secondary | 42 | 28.8 | ||

| Tertiary | 46 | 31.5 | - | |

| Number of female children of school age | 1 | 40 | 27.4 | |

| * | ||||

| 2 | 54 | 37.0 | ||

| 3 | 30 | 20.5 | - | |

| - | ||||

| 4 | 15 | 10.3 | ||

| - | ||||

| 5 or more | 7 | 4.8 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

Table 2 presents the results of specific aspects of attitude towards girl child education. Most (49.3%) of the respondents strongly agreed that it was necessary to send girls to school even though they would eventually get married, only a few (5.5%) wrongly affirmed. Most (45.9%) strongly agreed that there was need for girls to go to school and a larger proportion (60%) disagreed that preference should be given to educating the males. Most (82.2%) agreed that it was also important to educate the girl child with just 11.0% disagreeing. However, about 1/3rd (35.6%) of the respondent agreed that educating the girl child will increase their fight for gender inequality with only a few (1.4%) strongly disagreeing. 37.7% strongly agreed while 32.9% agreed that girls and boys alike should be given equal educational opportunities with 9.6% indifferent on this, 19.9% however disagreed.

| Attitude towards girl child education | Variables | Frequency ( n=146 ) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is necessary to send girls to school even though they will eventually get married | Strongly agree | 72 | 49.3 |

| Agree | 55 | 37.7 | |

| Indifferent | 11 | 7.5 | |

| Disagree | 6 | 4.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 1.4 | |

| There is need for girls to go to school even though their husband will take care of them | Strongly agree | 67 | 45.9 |

| Agree | 53 | 36.3 | |

| Indifferent | 9 | 6.2 | |

| Disagree | 10 | 6.8 | |

| Strongly disagree | 7 | 4.8 | |

| Preference should be given to male child education | Strongly agree | 15 | 10.3 |

| Agree | 26 | 17.8 | |

| Indifferent | 18 | 12.3 | |

| Disagree | 60 | 41.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 27 | 18.5 | |

| Educating girl child is important | Strongly agree | 64 | 43.8 |

| Agree | 56 | 38.4 | |

| Indifferent | 10 | 6.8 | |

| Disagree | 13 | 8.9 | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 2.1 | |

| Educating female children is a waste of time and money | strongly agree | 3 | 2.1 |

| Agree | 12 | 8.2 | |

| Indifferent | 13 | 8.9 | |

| Disagree | 87 | 59.6 | |

| strongly disagree | 31 | 21.2 | |

| It is better to spare the available money for boys education | Strongly agree | 9 | 6.2 |

| Agree | 27 | 18.5 | |

| Indifferent | 34 | 23.3 | |

| Disagree | 41 | 28.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 35 | 24.0 | |

| Educating a girl will increase their fight for gender equality | strongly agree | 36 | 24.7 |

| Agree | 52 | 35.6 | |

| Indifferent | 33 | 22.6 | |

| Disagree | 23 | 15.8 | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 1.4 | |

| Girls should be provided with equal educational opportunities | Strongly agree | 55 | 37.7 |

| Agree | 48 | 32.9 | |

| Indifferent | 14 | 9.6 | |

| Disagree | 29 | 19.9 |

Table 2: Specific aspects of attitude towards girl child education.

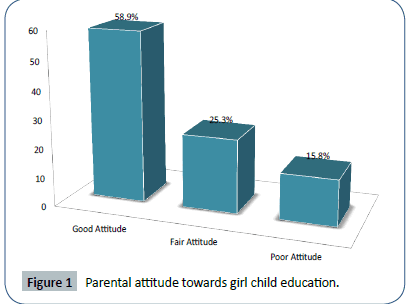

Analysis showed that 58.9% of the respondents had good attitude towards girl child education, while 25.3% and 15.8% had fair attitude and poor attitude respectively (Figure 1).

Table 3 shows the association between parental attitude and socio-demographic variable. There was a statistically significant association between age (X2=28.545, p=0.000), sex (X2=8.710, p=0.013), level of education (X2=49.426, p=0.000) and marital status (X2=19.475, p=0.003) with parental attitude towards girl child education. The proportion of parents with good attitude increase with decreasing age and with the highest proportion of parents with good attitude were seen among females, married and parents with tertiary level of education.

| Socio-demographics | Variables | Attitude level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good attitude (%) | Fair attitude (%) |

Poor attitude (%) |

X2 | P-value | ||

| Age group | 25 – 34 | 48 (81.4) | 8 (13.6) | 3 (5) | 28.545 | 0.000 |

| 35 – 44 | 22 (44.9) | 18 (36.7) | 9 (18.4) | |||

| 45 – 54 | 14 (42.4) | 11 (33.3) | 8 (24.2) | |||

| 55 – 64 | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | |||

| Sex | Male | 31 (47.7) | 24 (36.9) | 10 (15.4) | 8.710 | 0.013 |

| Female | 55 (67.9) | 13 (16.05) | 13 (16.05) | |||

| Level of education | None | 4 (26.7) | 9 (60) | 2 (13.3) | 49.426 | 0.000 |

| Primary | 12 (47) | 16 (37.2) | 15 (35.0) | |||

| Secondary | 29 (42) | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | |||

| Tertiary | 41 (89.1) | 5 (10.9) | 0 (0) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 69 (62.7) | 25 (23.0) | 16 (14.5) | 19.475 | 0.003 |

| Single | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | |||

| Divorced | 4 (50) | 0 (0) | 4 (50) | |||

| Separated | 7 (33.3) | 11 (52.4) | 3 (14.3) | |||

Table 3: The association between attitude of girl child education and socio-demographic variables.

Table 4 shows the specific aspect of parental practice of girl child education. Most of the parents (86.3%) motivated the educational interest of the female children while 13.7% don’t. Also 71.2% of respondent’s don’t give preference to educating the males while only 22.8% do. Most (89%) send their female children to school. A little above average 56.8% believe that parents in their neighborhood don’t give equal educational opportunities to their females compared to males. Most (89.7%) would send their girls to school despite the fact that they will marry later in life with only 10.3% who did otherwise.

| Practice of girl child education | Variable | Frequency (n=146 ) |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of females children of school going age in school | None | 14 | 9.6 |

| One | 58 | 39.7 | |

| Two | 59 | 40.4 | |

| Three | 15 | 10.3 | |

| Do you motivate the educational interest of female children | Yes | 126 | 86.3 |

| No | 20 | 13.7 | |

| Do you give preference to educating the boys | Yes | 42 | 28.8 |

| No | 104 | 71.2 | |

| Do your girls go to school often | Yes | 130 | 89.0 |

| No | 16 | 11.0 | |

| Do you educate your male children over the girls | Yes | 46 | 31.5 |

| No | 100 | 68.5 | |

| Do parents in your neighborhood prefer to educate their male children | Yes | 83 | 56.8 |

| No | 63 | 43.2 | |

| Will you send your girls to school even though they will marry | Yes | 131 | 89.7 |

| No | 15 | 10.3 |

Table 4: Specific aspects of practice of girl child education.

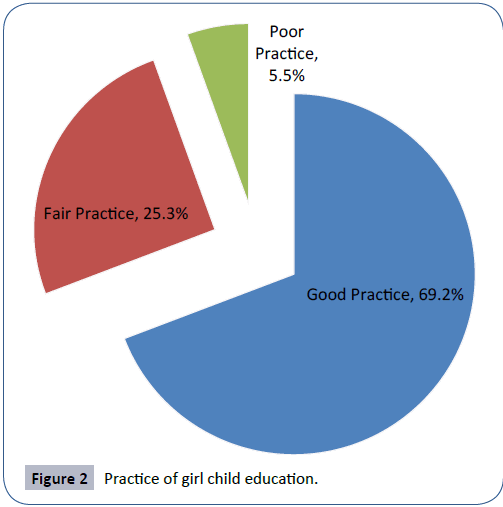

Figure 2 represents the practice of girl child education. Analysis showed that majority of the parents (69.2%) had good practice while 25.3% and 5.5% had fair and poor practice of girl child education. Table 5 showed the association between number of female children of school going age and the number of female children in school. It was observed that the higher the number of female children, the less likely their chances of going to school and there was a statistical significance (X2=92.701, p=0.000) between the number of female children of school age and those that were in school.

| Variables | Number of female children in school | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of female children of school age | None (%) |

One (%) |

Two (%) |

Three (%) |

X2 | P-value |

| 1 | 6 (15) | 34 (85) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| 2 | 5 (9.3) | 12 (22.2) | 37 (68.5) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| 3 | 2 (6.7) | 9 (30) | 12 (40) | 7 (23.3) | - | - |

| 4 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 8 (53.3) | 4 (26.7) | 92.701 | 0.000 |

| 5 or more | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (57.1) | - | - |

Table 5: The association between number of female children of school going age and the number of female children in school.

Table 6 shows the association between practice and sociodemographic variables of the parents. There was a statistically significant association between age (X2=22.816, p=0.001) and level of education (X2=21.186, p=0.002) of the parents and the practice of girl child education. There were higher proportions of those with good practice with decreasing age and higher proportion of parents with good practice had tertiary level of education. There was no significant association between practice of girl child education with marital status (X2=11.844, p=0.066) and sex (X2=0.452, p=0.798).

| Socio-demographics | Practice level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Good practice (%) | Fair practice (%) | Poor practice (%) |

X2 | P value | |

| Age group | 25 – 34 | 52 (88.1) | 7 (11.9) | 0 (0) | 22.816 | 0.001 |

| 35 – 44 | 26 (53.1) | 20 (40.8) | 3 (6.1) | - | - | |

| 45 – 54 | 21 (63.6) | 8 (24.2) | 4 (12.2) | - | - | |

| 55 – 64 | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | - | - | |

| Level of education | None | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 0 (0) | 21.186 | 0.002 |

| Primary | 24 (55.8) | 13 (30.2) | 6 (14) | - | - | |

| Secondary | 30 (71.4) | 10 (23.8) | 2 (4.7) | - | - | |

| Tertiary | 40 (87) | 6 (13) | 0 (0) | - | - | |

| Marital status | Married | 80 (72.7) | 25 (22.7) | 5 (4.5) | 11.844 | 0.066 |

| Single | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | - | - | |

| Divorced | 2 (25) | 4 (50) | 2 (25) | - | - | |

| Separated | 15 (71.4) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | - | - | |

| Sex | Male | 44 (67.7) | 18 (27.7) | 3 (4.6) | 0.452 | 0.798 |

| Female | 57 (70.4) | 19 (23.5) | 5 (6.1) | - | - | |

Table 6: The association between socio-demographic features and practice of the respondents.

Table 7 shows the specific aspects on factors affecting girl child education. Most (97.9%) of the respondents affirmed that it was not forbidden in their culture to send girls to school, only (2.1%) had a contrary view. Similarly, 98.6% said it was not forbidden in their religion to send girls to school with only 1.4% having a contrary view. Interestingly, most of the parents (86.7%) affirmed that their income didn’t play a role in their girl child education and 84.2% each agreed that their custom and tradition support girl child education and believed it morally right to send girls to school. However, a little above average (54.8%) said their daughters' behavior contributed to how much education they would give them. Table 8 shows the association between socio-demographic variables and some aspects of factors affecting girl child education. There was no statistical significance between religion, ethnicity and sex with the factors affecting girl child education. However, there was a statistical significance (X2=9.053, p=0.029) between the level of education and their moral believe towards sending girls to school, this proportion progressively increased with decreasing level of education.

| Factors affecting girl child education | Variables | Frequency (n = 146) |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is it forbidden in your culture to send girls to school | Yes | 3 | 2.1 |

| No | 143 | 97.9 | |

| Is it forbidden in your religion to educate a girl | Yes | 2 | 1.4 |

| No | 144 | 98.6 | |

| Does your income play a role in sending your girls to school | Yes | 20 | 13.7 |

| No | 126 | 86.3 | |

| Does your custom and tradition support girl child education | Yes | 123 | 84.2 |

| No | 23 | 15.8 | |

| It is morally wrong to send girls to school | Yes | 23 | 15.8 |

| No | 123 | 84.2 | |

| Does your daughters behavior contribute to your educating them | Yes | 80 | 54.8 |

| No | 66 | 45.2 |

Table 7: Specific aspects on factors affecting girl child education.

| Socio-demographic Variables | Is it forbidden in your religion to educate girl | X2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religion | Yes (%) | No (%) | ||

| Christians | 2 (1.7) | 114 (98.3) | 0.524 | 0.913 |

| Muslims | 0 (0) | 26 (0) | ||

| ATR | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | ||

| Others | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | ||

| Ethnicity | Is it forbidden in your culture to send girls to school | 14.046 | 0.081 | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Bini | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | ||

| Esan | 1 (1.1) | 90 (98.9) | ||

| Etsako | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | ||

| Hausa | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | ||

| Ibo | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | ||

| Ika | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | ||

| Owan | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | ||

| Urohbo | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | ||

| Sex | It is morally wrong to send girls to school | 6.933 | 0.08 | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Male | 16 (24.6) | 49 (75.4) | ||

| Female | 7 (8.6) | 74 (91.4) | ||

| Level of education | It is morally wrong to send girls to school | 9.053 | 0.029 | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| None | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | ||

| Primary | 11 (25.6) | 32 (74.4) | ||

| Secondary | 6 (14.3) | 36 (85.7) | ||

| Tertiary | 0 (0) | 46 (100) | ||

Table 8: The association between socio-demographic variables and some aspects of factors affecting girl child-education of the respondents.

Discussion

This study revealed that majority (58.9%) of the respondents had good attitude towards girl child education. The findings of this study tallies with a study done in Edo state on parental attitude and girl child education [12] but contradicts a study done in Midwestern state of Nigeria where there was low 32.5% positive attitude towards girl child education [13] and a study done in Akwa ibom were 60% of the respondents had poor attitude [14]. The reason for this good attitude observed in the study area may be due to increased awareness and enlightenment amongst this generation of parents compared to those in the past. Also, this high level of good attitude towards girl child education may have been influenced by the level of education by parents in the in study area considering that the area had two universities; which the community had benefited from over time.

On the aspect of the attitude towards the girl child education, majority of the respondents believed that it was necessary to send girls to school even though they would eventually get married and that educating the girl child was not a waste of time and money, this was in contrast to a study done on the assessment of parental attitude towards girl child education in Kaduna state [15] in which most of the respondents affirmed that educating the girl child was a waste of time and money since they would eventually get married out and their education would only profit their husbands and their families. Also from this study majority of the respondents disagreed to the fact that it was better to spare the available money for boys education at the expense of the girls, this was also not consistent with the findings in Kaduna state [15] were parents believe that boys will become the bread winners of the family and consequently must be educationally empowered for the task ahead. From the study, there was a statistically significant association between age (X2=28.545, p=0.000), sex (X2=8.710, p=0.013) level of education (X2=49.426, p=0.000) and marital status(X2=19.475, p=0.003). This might be due to the fact that those within the younger age group had better attitude, they are more aware and enlightened about the benefits of girl child education. In the same vein, females had better attitude probably due to gender identification. More so, those that were married as well as those with higher level of education had good attitude this might be due to better financial support with improved standard of living offered by their spouses and better orientation on benefit of girl child education.

Similarly, majority (69.2%) of respondents showed good practice of girl child education while only a few (5.5%) had poor practice. This is in contrast with a study done in Kaduna state [15] were poor practice was observed. The observation in our study further buttresses the fact that people from the southern part of Nigeria educate their female children more than those from the north. The actual practice of girl child education was assessed by comparing the number of female children of school going age against those that were in school (Table 5), this revealed that majority of girls of school going age where actually in school however the higher the number of female children the less likely their chances of going to school. The study showed that there was a statistical significant association between practice of girl child education and level of education (X2=9.053, P=0.029), however there was no significant relationship between religion, sex and culture and practice of girl child education. Those with higher level of education tend to practice girl child education more, because of their better knowledge on the benefits that accrues to a girl child when she is educated. This implies that in the study area, practice of girl child education is not influenced by religion, culture, gender nor societal beliefs. This is in contrast with a study done by Olomukoro and Omiunu [13] which revealed that cultural inhibition, erroneous interpretation of religious injunction, traditional practices, early betrothal of girls in marriage, gender insensitivity to educational environment and societal preference for male child resulted in poor practice of girl child education [13]. Same findings were also seen in a study done by kazaure where cultural values such as early child marriage militated against educating the girl child and a study done in Edo where Christian’s parents were found to have better disposition towards girl child education [12-15].

Conclusion

In conclusion, it has been found that parents in the study area have good attitude towards girl child education and though some factors such as lack of finance and large family size could reduce the chances of educating the girl child. Practice towards educating the girl child was found to be good. This negates the previous beliefs in Nigeria that the best education for the girl child is such that prepares her for a good wife, motherhood, raising children and providing family care.

References

- Goldstein H (2004) Education for All: The globalization of learning targets. Comparative Education 40: 5-6.

- Chabbott C (1998) Constructing educational consensus: International development professionals and the world conference on education for all. International Journal of Educational Development 18: 207-218.

- Igbuzor O (2006) The state of education in Nigeria. Economic and Policy Review 1: 47-50.

- Subrahmanian R (2002) Citizenship and the ‘right to education’: Perspectives from the Indian context. IDS bulletin 33: 1-10.

- Salman MF (2006) Female education in Ilorin emirate: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Ilorin: Centre of learning: A special publication to mark the 11th anniversary of the installation of HRH, Alhaji Ibrahim Sulu Gambari, CFR, and the 11th Emir of Ilorin. p. 157.

- Pettifor AE, Levandowski BA, MacPhail C, Padian NS, Cohen MS, et al. (2008) Keep them in school: The importance of education as a protective factor against HIV infection among young South African women. International Journal of Epidemiology 37: 1266-1273.

- Uko MJ, Okebe MG (2011) Repositioning social studies education for democratic challenges. ARASSE 1.

- Watt HM, Shapka JD, Morris ZA, Durik AM, Keating DP (2012) Motivational processes affecting high school mathematics participation, educational aspirations, and career plans: A comparison of samples from Australia, Canada, and the United States. Developmental Psychology 48: 1594.

- Sugai G, Horner RH, Dunlap G, Hieneman M, Lewis TJ, et al. (2000) Applying positive behavior support and functional ehavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 2: 131-143.

- Aziegbe FI (2006) Sediment sources, Redistribution, and management in Ekpoma, Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology 20: 259-268.

- Oyitso M, Olomukoro CO (2012) Enhancing women’s development through literacy education in Nigeria. Review of European Studies 4: 66.

- Obiageli OE, Paulette E (2015) Parental Attitude and Girl-Child Education in Edo State,Nigeria. Journal of Education and Social Research 5: 175.

- Egun AC, Tibi EU (2010) The gender gap in vocational education: Increasing girls access in the 21st century in the mid-western states of Nigeria. International Journal of Vocational and Technical Education 2: 18-21.

- Koziol NA, Arthur AM, Hawley LR, Bovaird JA, Bash KL, et al. (2015) Identifying, analyzing, and communicating rural: A quantitative perspective. Journal of Research in Rural Education 30: 1.

- Niles FS (1989) Parental attitudes toward female education in northern Nigeria. The Journal of Social Psychology 129: 13-20.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences