ISSN : 2393-8854

Global Journal of Research and Review

Can Small Towns Survive in a Global World?

Institute of Urban History, Stockholm University, Sweden

- *Corresponding Author:

- Lars Nilsson

Institute of Urban History

Stockholm University, Sweden

Tel: +46-08-16 33 94

E-mail: Lars.nilsson@historia.su.se

Received Date: October 26, 2018; Accepted Date: November 01, 2018; Published Date: November 06, 2018

Citation: Nilsson L (2018) Can Small Towns Survive in a Global World?. Glob J Res Rev Vol.5 No.2:9

DOI: 10.21767/2393-8854.100038

Abstract

This paper is about towns facing growth problems and the measures that have been taken to cope with urban shrinkage. One conclusion is that shrinking cities have not been able to regain population growth without external help, either from the state or from the market. Local measures from city authorities have not been enough. Finally, I discuss conditions for small cities to survive.

Keywords

Shrinking cities; Small towns; Globalisation; Post-industrialisation; Post-urbanism; Urban decline; Central place; Long waves

Introduction

Globalisation and the transition to a post-industrial economy at the end of the 20th century were in many European nations followed by an increasing number of shrinking cities. In fact, declining cities were sometimes much more frequent than growing cities. Many of those cities and towns that lost inhabitants were rather small in population size, but even middle-sized and major cities could have serious growth problems. Besides, shrinking cities had often an industrial background, and their economy had mostly been dominated by one or a few branches and companies. The urban demographic and economic expansion had generally started during the 19th century industrialisation and with some interruptions continued up to the de-industrialisation in the 1960s and 1970s. From a geographical point of view, shrinking cities were spread all over the nation but with concentration to certain regions, which have been called rustbelts [1].

Another new trend by the late 20th century was metropolisation. At the same time as a majority of all cities and towns shrank, metropolitan areas and major cities grew quickly. This growth process started often after a period of metropolitan decline caused among other factors by the so called green wave. Many people preferred in the 1970s to flee the major cities and settle down in small towns or on the rural countryside. The urban-rural population balance stabilised at a high level, and the space for further increase of the urban degree was only marginal.

Post-industrial metropolitan growth has demographically been caused by urban to urban migration. Net migration streams have gone from small towns to major cities and not, as previously, from rural to urban areas. Therefore, the urbanisation rate has remained rather constant. Other important sources for postindustrial metropolitan growth have been immigration, not least of refugees, and a high net-birth rate.

These new tendencies mean that we may talk about a post-urban world. The urban degree is so high that it cannot increase much more, and most population changes take place inside the urban system. Urban norms and values are dominating even on the rural countryside.

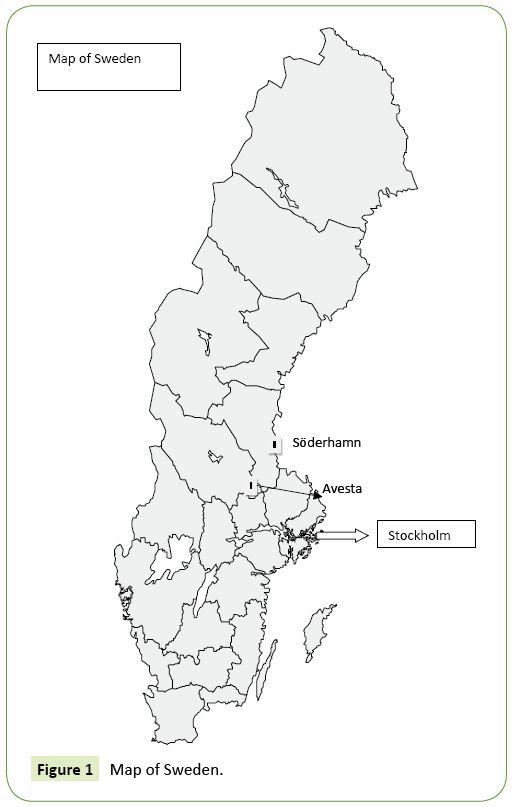

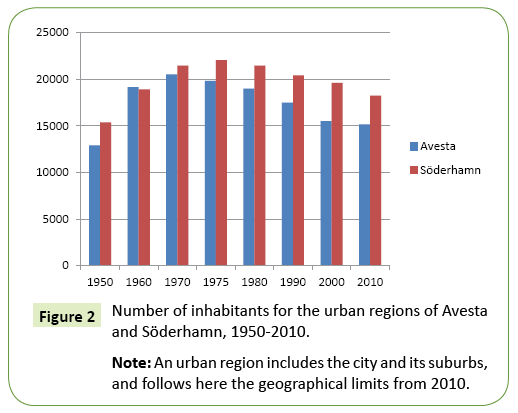

In this article I have will discuss the possibilities for small towns to survive in a global and post-industrial (post urban) world with examples from two Swedish shrinking towns, Avesta and Söderhamn. They are located not so very far from each other, 200-300 kilometres north of Stockholm, in what we can call the Swedish rustbelt (Figure 1). Their decline started with the deindustrialisation in the 1970s. The local authorities have since then used a wide variety of measures to regain growth. Today, both municipalities have today around 20,000-25,000 inhabitants, including both urban and rural areas (Figure 2) [2].

Two Shrinking Towns

Avesta

Avesta is located along the river Dalälven in the interior of the region Bergslagen, well-known for its mines and big manufacturing companies. It was the combination of waterfalls, and the rich supply of copper ore, iron ore and woods that made this site suitable for industrial production. Avesta became in the 17th century the main centre for Swedish copper production. Copper ore was delivered by horse transports from the copper mine in Falun, 68 kilometres north of Avesta, and charcoal from farmers in the surroundings. Smiths were recruited both from Sweden and other nations. The copper production became so important that Avesta was granted privileges as a town in 1641. Avesta got also monopoly for the production of coins. The factory may during its heydays have been the largest in the world of its kind [3].

The town privileges were recalled in 1686, copper production failed and Avesta stagnated and became a shrinking town. A new era began in the 19th century based on iron and steel production. The international demand for Swedish iron and steel increased substantially during industrialisation, and the iron factory in Avesta, established in 1821, developed quickly since the Johnson family became sole owners in 1906. The number of inhabitants rose in a few years from 2,000 to 3,600.

The expansion was also stimulated by the construction of the railway system from Stockholm to Northern Sweden. Avesta was originally intended to be a central node in the Swedish Northern railway system, but due to geo-technical problems the railway station had to be located in a neighbouring place. Anyway, the advent of the railway had also positive effects on Avesta. Population increased up to 5,000 in 1919, when Avesta got back its status as a town.

During the economic crisis of the 1920s and the 1930s Avesta became once again a shrinking town. It lasted until the late 1930s before the population figure was back at the same level as in 1919. The rebuilding of Europe after World War II meant a very high demand for Swedish iron and steel. Avesta Iron Works increased production and employment and kept its position as one of the leading Swedish steel producers. There were also other big factories in the neighbourhood of Avesta on the other shore of the river Dalälven, for example an aluminium company, a chlorate factory and a phosphate industry.

The population of Avesta increased of course significantly during these fruitful years. One obstacle for further growth was the scarcity of land. Huge tracts of land were owned by the Iron Works, and not for sale. Anyhow, the number of inhabitants amounted to 20,000 in the late 1960s, suburbs included.

Increasing international competition and rising oil prices caused serious growth problems for the entire Swedish steel industry in the 1970s. The branch was totally reorganised, including among else rationalisation of production and fusion into fewer and larger units. Avesta Iron Works survived this process, but got new owners in several stages ending up with the Finnish State company Outokumpu.

Avesta Iron Works is still today an important enterprise in Avesta, but with fewer employees than before. The aluminium factory, on the other side of the river Dalälven, closed down in 1975, the chlorate and phosphate companies even earlier. This de-industrialisation process resulted immediately in population decline. The number of inhabitants in Avesta urban region fell from 20,000 in 1970 to ca 15,000 in 2010. This gives in relative terms a reduction of 25 per cent in forty years.

Söderhamn

Town privileges for Söderhamn were issued in 1620 due to the establishment of an arms factory. Arms forging were an old speciality in this region, and through the privileges the production was concentrated to the town. Only six more Swedish towns had such factories during the 17th century, when Sweden was a great power in European politics. Production fell in the 18th century, and in 1813 the factory was definitely closed down. The burghers had to rely on the traditional urban trades, such as handicraft, commerce and fishing [4].

A new epoch started in mid-19th century with the sawmill industry, whose initial expansion was financed by capital from Stockholm and Göteborg. This was at the eve of Sweden´s industrialisation, and Söderhamn had a favourable geographical location as a port city at the southern coast line of the Gulf of Bothnia. The rich stock of forests could easily be transported on the river Ljusnan from the interior of the region to Söderhamn at the coast. Several steam-driven sawmills were established around Söderhamn, together with for example timber yards. The final products were to a great extent exported, and shipped to national customers as well. The economic base was, as for Avesta, much wider than the local and regional market in itself. Population size was determined by the city´s function as an export node.

The sawmill expansion gave a lot of positive external effects on other trades. An engineering industry started for example, for production of machines and equipment for the sawmill industry and other companies. Infrastructural investments in roads, railways, waterways, harbours, residential houses etcetera became as well necessary. The economy flourished, and the number of inhabitants in Söderhamn rose from less than 2,000 persons in mid-19th century to more than 10,000 in 1890. Besides, many new urban localities developed around the factories outside the city´s administrative area.

The sawmill production reached its peak at the end of the century. Some factories closed down because of increasing international competition from Finland and Russia. Besides, the exploitation of the Swedish forests had been so intense that the raw materials for the sawmill industry became a scarce resource. Production was concentrated to fewer and bigger units. Population and economy stagnated. The sawmill decline was however counterbalanced by an upswing for the paper pulp industry which stabilised the situation. Anyhow, Söderhamn was still strongly dependent on forest industries.

The great depression in the 1930s had serious consequences for Söderhamn. Only 8 out of 23 sawmills survived. The paper pulp industry got also severe problems and the effects on the other trades were wide-ranging. Population declined to below 10,000 inhabitants. The situation did not improve until after the Second World War. The recovery became possible because of two big investments, one by the Swedish Government, and one by the phone company Ericsson. The Swedish State decided in 1945 to localise an arm wing to Söderhamn, and Ericsson invested shortly afterwards in a new production unit. This resulted in a more differentiated economy but Söderhamn was still strongly dependent on manufacturing, and not least forest industries. The economy flourished again, and the number of inhabitants increased up to 20,000 in 1970, suburbs included.

The strong dependency on manufacturing meant that Söderhamn once more came into a precarious situation, when deindustrialisation began in Sweden. The first signs of an upcoming crisis became visible in mid-1970s. Several pulp factories reduced production and fired workers. In the next ten years more than one thousand industrial jobs were lost, due to a mix of reduced production and rationalisations. The amount of lost jobs was the same for the following ten years. Many factories could not survive during the new post-industrial conditions. Initially, the forest industries had the greatest economic problems, but even the phone fabric and other engineering industries reduced production and fired people.

In the 1990s the Swedish Parliament voted for a new defence policy. The number of military units should generally be reduced, and the military division in Söderhamn was closed down in 1998. A few years later the phone company Ericson sold its works in Söderhamn to the American company Emerson. They stooped production in 2004 and liquidated the factory. As we remember, the arm wing and the phone factory saved Söderhamn from the former economic crises, now they were both gone.

In spite of the deindustrialisation, manufacturing is still an important sector in Söderhamn, and comparatively stronger represented than in most other Swedish cities. One of the largest companies today is Arizona Chemical with head office in Florida. About 100 workers are engaged in the distillation of raw pine oil in a suburb to Söderhamn, Sandarne. This is the largest unit in the world for pine oil production. Arizona Chemical is also an example on how global capital and multinational companies have gradually taken over the industries, and the owners are not present in the city as it could be when industrialisation began.

Local measures against population decline

External help

During industrial times Swedish cities facing economic crises usually relied on help from the Government. A combination of State measures and private investments in new factories by leading manufacturing companies had in the 1950s and the 1960s been a successful strategy. It was seen as a national interest that the State and the private capital should work together to solve local crises on the labour market. Only the State had the necessary overview to decide how to use scarce resources in the best way. Municipalities were therefore by law forbidden to sponsor private companies, and compete with each other [5].

Initially, the local authorities of both Avesta and Söderhamn hoped for external help to handle the upcoming industrial crisis in the 1970s. The local authorities of Söderhamn, for example, expected that private entrepreneurs now should realise their previous plans of building a new large-scale paper mill close to the city. Thousands of people demonstrated and claimed support from the State. Local delegations were sent to Stockholm to argue for the need of external money to save the jobs by setting up new production units to replace the losses [6].

Investments in a paper mill were of course not at all realistic in a situation with extensive de-industrialisation, and the State could not any longer assist shrinking cities in the same manner as before. Instead, local authorities were urged to solve their own problems without external subsidises. All previous restrictions towards municipal sponsoring of private companies, place marketing, and local economic policies were abolished.

Local economic policies

During these new circumstances many Swedish municipalities, including Avesta and Söderhamn, began almost immediately with active place marketing and sponsoring of private businesses. Local economic policies were formulated and decided by the city councils. The local administration was strengthened by special offices for economy and commerce. By such measures lost industrial jobs were supposed to be replaced by new industrial jobs. It was a local industrial replacement strategy.

The local authorities of Söderhamn pursued a very active local economic policy with focus on small and middle-sized firms. A number of companies owned by the city itself were set up to promote private investments, and attract new ones. The municipality took even over a chain factory that was threatened by bankruptcy. Shortly afterwards this factory had anyway to close down and liquidate with substantial economic losses for the city.

The local authorities of Avesta used similar strategies as the colleagues in Söderhamn. A municipal foundation, later reorganised to a municipal company, were founded to attract and support new investments. Potential investors could lease necessary premises, and get loans on favourable conditions. These measures resulted in the establishment of a number of new small and medium-sized firms. But the newcomers were only short-lived. Within a few years they closed down or left Avesta, and were sometimes replaced by new short-lived companies.

This industrial replacement policy gave in both cites very meagre results. The labour market did not improve. Population decline continued. It turned out to be more or less impossible to replace lost industrial jobs with new jobs of the same kind. The economic crisis deepened and was followed by deficits in the municipal budget. This financial crisis was caused by diminishing tax revenues and increasing municipal costs. Avesta tried to improve the public finances by selling out municipal property, for example the energy company and housing foundations.

The local authorities of Söderhamn handled the excess of housing in another way. Instead of selling out municipal property they decided to turn down the surplus of tenement houses. Such actions could be subsidised by the State. The State also assisted Söderhamn by a special “package”, with focus on IT and education, to compensate for the loss of the military wing.

Culture and tourism

When the industrial replacement strategy failed, the local authorities choose a new course directed towards culture and tourism. Culture as well as tourism had been expansive branches in the post-industrial Swedish economy. The new strategy seemed therefore to have good potential for regaining population growth. The loss of manufacturing occupations should be replaced by investments in culture, cultural heritage, tourism, and services.

A former industrial area in Avesta, named the Northern Works, was in the 1990s rebuild to a cultural centre. One of the old buildings became site for an international exhibition – Avesta Art – of contemporary art. Another building was renovated to an industrial museum reminding of Avesta´s long industrial history. Later on the exhibition centre and the museum has been complemented with an art academy. The Northern Works includes as well a sports arena and small industrial firms. The area has been marketed as The Copper Valley with reference to the previous copper production from the 17th century [7].

The art exhibition, Avesta Art, became a great success and has since the start in 1995 attracted thousands of visitors every year. In 2010 the number of visitors exceeded 20,000 which was almost as many as the total population of the municipality.

Avesta´s long tradition of mining and manufacturing has, however, not been totally forgotten. A rising demand for minerals has given great expectations for a flourishing future based on the region´s wide-ranging knowledge of mining. Several industrial projects have been initiated in cooperation with other municipalities, regional authorities and university colleges [8].

The local authorities of Söderhamn gradually changed strategy in the same way as the colleagues in Avesta when all efforts to re-industrialise the city failed, as well as the state package. But still in the 1980s, urban planning gave priority to restore the old industrial structure. However, the ambition to return to the same number of inhabitants as before the industrial crisis was gradually weakened and finally seen as unrealistic. Shrinking was more or less accepted and the goal became to stabilise economy and population on a lower level than before. The urban planning from mid 1990s emphasises therefore tourism, cultural heritage, museums and services, instead of large-scale industrial jobs [9].

City renewal

The local authorities of both cities have, besides all other actions, used urban renewal as a means to make the city more attractive for potential visitors, investors, and inhabitants. Several proposals for a restructuring of the inner city were in the 1960s presented for the city council of Avesta. The planning was accomplished in close collaboration with the local merchants. Because of uncertain industrial forecasts the local authorities wanted to rebuild and market Avesta as a commercial centre for the entire region. A property company partly owned by the city was established in 1969 to facilitate the restructuring process. The new city centre was opened a few years later (1973) with a pathway through the city centre and parking in the outskirts.

A new main road for the thorough traffic was build outside the city. Previously all cars, buses, and lorries had to pass through central Avesta irrespective of their final destination. An external shopping centre was established in the 1980s at a traffic hub along the new main road.

City planning has later on been updated several times for example in 2010. A new travel centre was then proposed combining buses and trains with a pathway to the Copper Valley. It was presumed that the Copper Valley´s accessibility should increase in that way as well as its attractiveness.

The local authorities of Söderhamn tried in the same manner to strengthen the city´s role as a regional trade centre. In the early 1990s an external shopping centre was opened along the motorway, E 4, outside Söderhamn with all facilities such a centre was supposed to offer. The need for a modernisation of the inner city was emphasised in a city plan from 1998. A careful restructuring and densification of the central quarters was proposed and decided. The same goals were underlined in the 2015 city plan, and formulated as “a living city centre with a feeling of archipelago”.

The efforts to encourage entrepreneurship and innovations survived in projects such as “Drivkraft”, “Högtrycket” and “Ungdomslyftet”. They emanated from the program “Söderhamn Vision 2012”, which had education and diversity as a ground pillar. Besides, the projects had the ambition to create a positive image of Söderhamn, and in that way make the city attractive [10].

A new railway station in the outskirts of central Söderhamn was opened in 1997 and closely linked to local buses. The city´s accessibility and attractiveness was supposed to increase by linking long-distance and short-distance travelling. The old centrally placed railway station became a cultural heritage and tourist goal. The new station resulted in an increase of commuting, especially out-commuting, from Söderhamn [11].

Summing up

The urban local authorities of Söderhamn and Avesta have thus by a number of different measures tried to regain population growth after decades of decline. In the first stage they hoped for external help to re-industrialise the cities. Those efforts were however not successful. In the next step the local authorities tried to reindustrialise their towns by own means such as local economic policies, sponsoring of private businesses and place marketing. Later on, they turned to culture and tourism in combination with programs for urban renewal. Furthermore, they re-structured the towns towards regional commercial centres. But all measures were in vain. The number of inhabitants continued to decline.

A New Population Trend after 30-40 Years of Decline?

Population statistics for the period 2010 to 2015 reveals that the number of inhabitants has increased in Avesta as well as in Söderhamn. But not only in these two previously shrinking cities. In fact, most Swedish cities registered population increases and the number of shrinking cities returned to the same low level as in the 1950s and the 1960s. A “normal” level of shrinking cities was about one out of three in late industrialism.

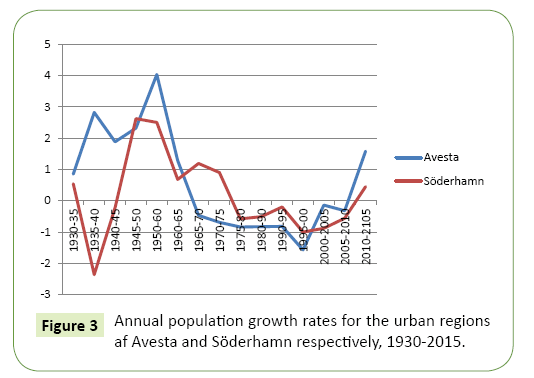

Avesta´s population increased with 1.58 per cent per year in the period 2010-2015, which was far above the national average of 1.05 per cent. Suddenly, Avesta became one of the more expansive Swedish cities. The annual population growth of Söderhamn was more modest or 0.49 percent (Figure 3) [12].

The demographic explanation for these new traits is immigration, and foremost immigration of refugees. Both cities had since long ago registered net-immigration, but this surplus of foreign migrants was not enough to cover for losses by net out-migration to other Swedish municipalities and net deficits of births. This situation changed dramatically in the years 2010-2015. The number of net-immigrants increased so much that it covered not only population losses by net domestic out-migration but also population decline because of more deaths than births (Table 1). Avesta even had a small surplus of domestic in-migration.

Table 1 Population changes in the municipalities of Avesta and Söderhamn, 2001-2015.

| Net births | Net immigration | Net domestic migration | Population change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avesta | ||||

| 2001-2005 | -666 | 262 | -6 | -410 |

| 2006-2010 | -436 | 628 | -554 | -554 |

| 2011-2015 | -367 | 1493 | 53 | 1179 |

| Söderhamn | ||||

| 2001-2005 | -708 | 233 | -691 | -1166 |

| 2006-2010 | -695 | 1241 | -1384 | -838 |

| 2011-2015 | -492 | 1802 | -1174 | 136 |

The labour market did however not expand very much. Söderhamn had an increase of employment of only two per cent in the period 2010-2015, and Avesta had lower employment in 2015 than in 2010. The influx of refugees made it possible for Avesta and many other cities as well to grow demographically even if the labour market did not improve at all. This cannot be a sustainable growth in the long run.

Even if the labour market did not expand there were important structural changes. Avesta saw a re-structuring from manufacturing mainly towards education, health care, medical care, and social care. These branches were also generally very expansive in Sweden during this period, especially among cites that like Avesta turned from stagnation to population growth. Söderhamn, on the other hand, totally missed these expansive branches. Instead, there was a re-structuring from manufacturing towards the less expansive branches of public administration, commerce and cultural services. This may explain the differences in population growth between Avesta and Söderhamn in 2010- 2015.

If these new tendencies will sustain in the long rum is of course impossible to know today. We must wait until we have data sets for longer time spans than five years.

Can Small Cities Survive?

Cities normally grew in waves. Periods of expansion are followed by contraction and then a phase of growth may start again. Economic crises have for centuries been a normal part of urban life in Avesta as well as in Söderhamn. Both cities have recovered mainly thanks to external forces and not by own actions.

The recent growth problems have in the same manner as previous crises been brought to a halt at least temporarily by external forces far outside the control of the local authorities. Political, military, and economic conflicts in northern Africa and the Middle East have sent hundreds of refugees to such remote places as Avesta and Söderhamn. The arrival of refugees has broken the falling population trend. This new upswing is however not the consequence of a flourishing labour market as previous population growth periods were. Therefore it is uncertain if the growth can sustain in the long run. Hopefully, the newcomers will contribute with impetus to the local economy and a sustainable expansion.

In this article I have tried to demonstrate that measures from local authorities have not been enough for a shrinking city to regain population growth. This is not to say that local policies are of no value at all. They may very well soften the negative effects of economic stagnation even if they cannot cope with the latent structural mechanisms behind the decline. But to regain population growth external forces seem to be necessary.

Urban decline is of course not a new phenomenon. During each decade of the industrial era about one third of all Swedish urban regions lost inhabitants. However, these losses did not normally last very long. Stagnation occurred generally without population loss.

Urban decline has been much deeper and more frequent since the start of the post-industrial and global era. Many urban regions had therefore fewer inhabitants in 2010 compared to the 1970s. This leads to the question: can urban decline continue forever, if there is no external stimulus? My answer is: probably not as long as the city upholds the role of a central place. A central place needs a minimum number of inhabitants to be able to deliver services to its own citizens and to those living in the surroundings. Sooner or later a minimum point will be reached, population decline may stoop, and the number of inhabitants will thereafter be more stable.

Central place duties can of course also be reduced. Centralisation of for example education, health care, banking, commerce, and other services can affect many towns in a negative way. The supply of services of various kinds diminishes, and then, the minimum population level for service distribution will be lowered. The town can be downgraded to a lower central place level, and the risk for shrinking increases. The digital revolution may as well reduce central place functions and be a threat towards the survival of small towns.

Besides being central places Avesta and Söderhamn were also export nodes. Their population sizes were determined by this latter function. De-industrialization meant that the export sector needed less people and resources than before which of course also resulted in lower demand for central services. The balance between central place functions and export functions changed in favour of the former. Population size had to be adjusted to these new circumstances, which meant shrinkage.

Conclusion

After 30-40 years of decline Avesta and Söderhamn had perhaps reached, or were close to, that minimum population level necessary for fulfilling their roles as central places. If so, decline would not have continued much longer. Besides, they still maintained export functions. Anyhow, immigration of refugees must have been the most important factor behind thee recovery in 2010-2015. Thus, as previously, external factors were decisive for the regaining of population growth.

Swedish urban development can be described in waves with a length of about forty years. The periodisation has been as follows: c. 1840 – 1870s/1880s – 1920/1930s – c. 1970 – c. 2010. Each period has had its own dynamic branches which have favoured some cities and disfavoured others. If a new epoch, with fewer shrinking cities and new prime motors, have started around 2010 is of course still impossible to know.

References

- Nilsson L (2011) The coming of the post-industrial city: Challenges and responses in Western European urban development since 1950. Stockholm.

- Nilsson L, Båve E (2016) Shrinking resorts Avesta and Söderhamn as post-industrial societies. Stockholm.

- Nilsson L (2011) The population in urban areas 1950-2005. Stockholm.

- Jörnmark J (2007) Abandoned places. Stockholm.

- Nilsson L, Forsell H (2013) 150 years of self-government - municipalities and county councils in change. Stockholm.

- Lindberg H (2002) To face the crisis. Political change at local level during the industrial crisis in Söderhamn 1975-1985. Uppsala, pp: 104-128.

- Geijerstam JA (2007) Industrial heritage in change. Avesta.

- Storm A (2005) Koppardalen: About history's place in the transformation of an industrial area. Stockholm.

- kommunarkiv S (1995) In-depth overview plans. Söderhamn.

- Eva L, Åsa FL (2014) Driving power Söderhamn: results and reflection from a scientific perspective.

- Mikael Vallström (2011) To regain the future.

- Nilsson L (2011) The population in urban areas 1950-2005. Stockholm.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences